Liu Xiaodong's Homecoming at UCCA Edge

UCCA | Sponsored Content

Liu Xiaodong's solo exhibition Liu Xiaodong: Your Friends at Shanghai's UCCA Edge (8 August–10 October 2021) begins and ends with Liu's homecoming.

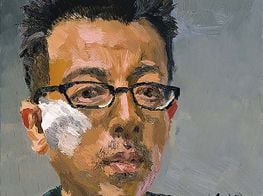

Liu Xiaodong, Self-Portrait (2010). Exhibition view: Your Friends, UCCA Edge, Shanghai (8 August–10 October 2021). Courtesy UCCA Edge.

In a neat cyclical narrative of youthful uncertainty turning to unconcerned middle age, this homecoming is best captured with two self-portraits.

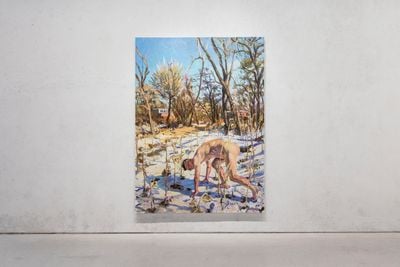

Opening the exhibition is Self-Portrait (2010), painted during the first return visit to his hometown of Jincheng in 30 years; the tightly cropped frame presents the artist looking out at the viewer pensively, serious, wary. Closing the show, Self-Portrait in Heitukeng (2020) captures Liu Xiaodong naked in a field of snow and wilting sunflowers, his pale, sagging body bent over as if about to show that he can still do push-ups, the pose unserious, insouciant.

In between these moments, the exhibition brings together examples of Liu's renowned neorealist painting practice and his eye for the precarity of others, often caused by the external realities of social and economic development.

The 'Jincheng Story' and 'Hometown Boy' series feature portraits of friends and neighbours from his birthplace, a small, remote factory town in Liaoning Province. By the time Liu returned, the paper mill that had sustained life in the town was winding down, leaving many, like the anxious-looking woman from Xiao Dou Hanging out at the Pool Hall (2010), terminally unemployed.

Other paintings from the series, like Xuzi at Home (2010), feature older men, topless in the summer heat, eating, smoking, waiting. Liu declines to present any political or emotional narration, instead things are as they are, and change has a cost.

Liu's interest in those left adrift by uncontrollable forces—environmental crisis, natural disaster, poverty, war—continues with his exploration of the Chinatowns of Prato, the ship breaking yards of Bangladesh, and the refugee camps of Europe.

Yet, while the portraits of diaspora Chinese communities resonate with an intimacy perhaps born of identification and understanding, Liu's paintings of the ship breakers of Chittagong and the displaced Syrian communities of northern Europe convey a sense of distance and unease.

Presenting painting as an act of reconciliation and acceptance, Liu asks us to reflect on our own connections, and to the barriers we may have erected that prevent them.

In Chinatown 1 (2015) for example, his subjects appear close-up, as if walking toward him; smiling, one pats a dog, and the atmosphere is convivial. Likewise in Chinatown 4 (2016), while the scene is full of tension, the strain clearly emanates from the mahjong game that dominates the centrefield, while the people—family, colleagues—are clearly at ease.

By comparison, Bangladeshi labourers have their faces turned away or obscured in works presented as diptychs, the left side showing their dismal labour while the right appearing like abstract colour panels. They are in fact studies of rust and steel—the bodies of men and the recycled materials hold equal value here.

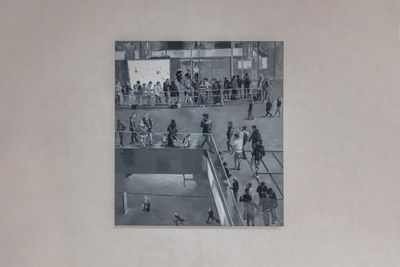

The refugees, on the other hand, are presented either alone, close-up, challenging the viewer; or from a distance, crowding and menacing. In Things Aren't as Bad as They Could Be (2017), the large group portrait was apparently inspired by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo's The Fourth Estate (1901).

But where Volpedo depicts a worker's strike with calm and quiet dignity, Things Aren't as Bad as They Could Be depicts the refugees clustered at the Milano Centrale railway station, hemmed by brick walls and bars, simmering with tension.

Two figures near the centre captures attention: one hides a hand beneath a jacket, looking defensive and weary, while the other drops his shaved and gleaming head, brimming with angry exasperation.

In the foreground, a woman holds aloft a baby, their faces hidden. She appears rooted to the spot, perhaps because there is nowhere else to go. In contrast, the woman in Volpedo's painting holds her head confidently and strides forward, willing the crowd to follow, the babe in her arms unperturbed.

Hung high above is Refugee 1 (2015), which depicts the exiles at Vienna Central Station from far above and in black and white, as if viewed through a security camera. Certainly, the differences in how Liu worked with the communities he paints has contributed a certain remove.

Liu has said of his work documenting refugees that language and cultural barriers informed the compositional framing. 'I can only observe the refugees from a distance,' he said, 'as though separated by a glass window.'1 One feels that this inability to connect makes for unsympathetic portrayals.

The exhibition continues with a voluminous series of watercolours, made during Liu's extended stay in New York due to the pandemic. Finding himself trapped in the normally vibrant city, the artist began to document the oddity of the still and quiet streets.

Despite knowing the context of uncertainty and fear in the early days of the pandemic, particularly for Chinese, with their worries for family back home and the potential of facing senseless violence abroad, these works evince a serenity and poignancy that foreshadows the final series of the show, 'Your Friends'.

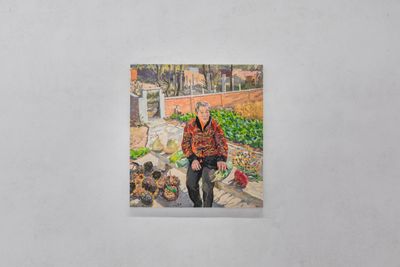

Completed on his return to Beijing, these large and densely detailed works feature his closest friends from the three decades spent working in Beijing. His subjects include writer Ah Cheng and film directors Wang Xiaoshuai and Zhang Yuan, as well as Liu's mother, brother, and his wife, Yu Hong.

Here the influence of familial ties and the bonds of love nurtured over time are on full display. The object labels also become more familiar, providing personal details and small anecdotes about each person, for example noting that a distant relative portrayed as tall, thin, and diffident-looking in Yang Hua (2020) is 'diligent and quick-witted, but also stubborn and selfish.'

In the text for Mom (2020), Liu describes the difficulty of portraying his mother without her appearing bitter. It goes on to relate that Liu painted this portrait keeping in mind her warmth and dependability rather than the absences due to her circumstances and hardworking nature.

Presenting painting as an act of reconciliation and acceptance, Liu asks us to reflect on our own connections, and to the barriers we may have erected that prevent them. —[O]