Anni Albers: The Fabric of Modernism

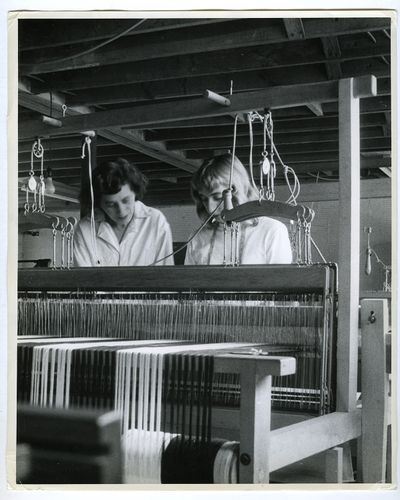

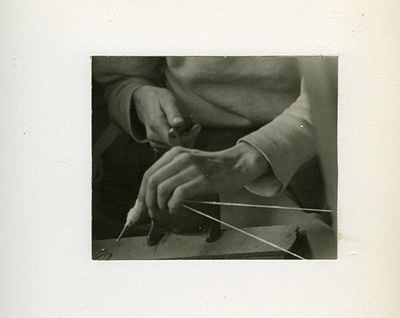

Anni Albers winding a bobbin at Black Mountain College (1941). Courtesy The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. Photo: Claude Stoller.

Walking through the Anni Albers exhibition at the K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, in Düsseldorf this summer (9 June–9 September 2018), I couldn't help thinking about the 1944 poem by American dancer and artist Raymond Duncan, 'I Sing the Weaver'. The poem talks about weaving as a practice linking a weaver's body to the world; a view that expresses the ethos of Akademia, a commune that Duncan co-ran in Paris with the Latvian dancer Aia Bertrand from the 1910s to the 1970s. Weaving was a practical embodiment of the commune's anti-consumerist ideology—members devoted a considerable amount of time making the tunics they wore. Beyond manifesting the potential for self-sustainability, the commune was also concerned with reviving and preserving an age-old handicraft that was being lost to technological progress.

While members of Akademia saw weaving as an antithesis to modern technology, their approach to weaving as a radical craft finds resonance in the work of Anni Albers, even if Albers considered the relationship between weaving and technology a holistic one. Her essays and books on the craft, like On Weaving (1965), were nothing like instruction manuals. As philosophical and theoretical texts exploring the history of both handicraft and manufactured weaving, they looked beyond learning or teaching the medium, or describing its practical usage, and instead explored the visual and structural components that elevated the craft into a practice that uniquely integrated art with life.1

Albers' desire to create horizontality among disciplines was reflected in her K20 exhibition, organised with the Tate Modern in London, where the show will open on 11 October (showing to 27 January 2019).Highlighting the remarkable contributions Albers made to modernism, this extensive retrospective was choreographed to grant equal value to the many facets of the artist's practice—from weavings, design sketches, textile samples, and jewellery designs, to documentation of Albers' theoretical writing, and archival photographs of weaving workshops she staged as a teacher at the famed Bauhaus school, and Black Mountain College in North Carolina. One story that encapsulates Albers' experimental approach is an exercise she gave to her students when her workshop at Black Mountain College moved to a new building in 1940. The rooms did yet not have looms, so Albers tasked her students with seeking whatever materials they could find, and organising them into a grid.

Albers enrolled with the Bauhaus in 1922. She intended to study painting, but was assigned to the weaving workshop instead the following year, also known as 'the women's class'.2 Regardless of the professed equality of disciplines and genders at the school, hierarchies and distinctions remained between both, with architecture perceived as the most important subject. Notwithstanding, Albers pursued her studies with radical persistence. Together with other female weavers and textile designers like Gunta Stölzl, she contributed to the development of the weaving department and the practice itself, working on different scales, from sketches and small-sized samples, to woven objects for domestic and public settings. She and her colleagues also supplemented practical work with theoretical writings around craft, with Albers describing 'weaving in any form' as 'a constructive process'.3

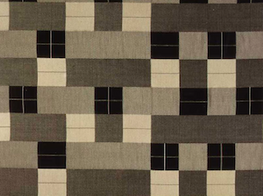

Inspired by the artist Paul Klee, one of her teachers, Albers approached weaving as a painter, imbuing her work with the aesthetics, theories, and methods of abstraction that were fermenting at the time. In particular, she exercised colour penetration, where weft and warp threads of different colours 'penetrated' each other through weaving, thus creating a subtly gradated colour range. Her cotton and silk wall hanging Black White Yellow, first made as a student in 1926 and re-woven 1965, is an irregular arrangement of different-sized rectangular shapes in varying colours (black, white, yellow and their half-tints), with a manipulation of threads creating gradations one might expect from a painted work of geometric abstraction.

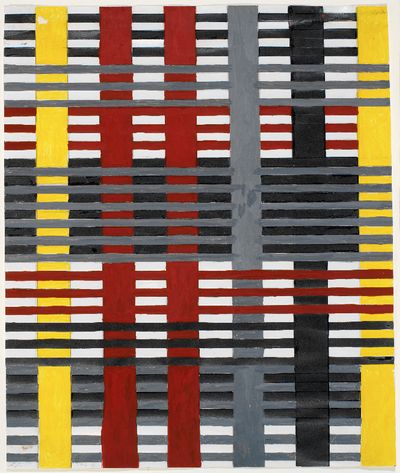

Three gouache paintings included in the K20 show, which Albers created during her student years, include a design for a silk tapestry (1925), and two designs from 1926 detailing a realised and unrealised wall hanging. In each one, an uneven grid is formed by vertical stripes of yellow, red, grey and black crossed by thinner black, grey and red lines. Emulating the criss-crossing threads of fabric, they are paintings in their own right.

Graduating in 1928, Albers went straight into teaching, leading a weaving workshop at the Bauhaus until 1933, when she—like many others of Jewish descent—emigrated to the USA after the National Socialists came to power in Germany. Arriving at Black Mountain College, she established a weaving workshop and continued her pioneering investigations, experimenting with 'ideas and techniques that took her work in new directions, notably away from the strictly gridded compositions she had favoured at the Bauhaus.'4

One example of this stylistic shift is a 1965 memorial to the Holocaust that the Jewish Museum in New York commissioned her to make. Six Prayers (1965–1966), included in the K20 show, is an impressive wall hanging consisting of six panels made from cotton, linen, bast and silver thread that hang closely together—it is rarely shown today due to its fragility. Demonstrating a more organic rhythm than her earlier works, shimmering beige, black, white, and silver strands are tangled together in loops, waves and knots. Aside from being a visually compelling merger of traditional and modern techniques, Six Prayers is a powerful example of a political message worked into an abstract weaving.

Six Prayers is also an example of the evolution in style that marked Albers' move to the United States—no doubt influenced by her travels to Mexico City, where artist Diego Rivera and architect Luis Barragán, among many others, were living and working. Albers had a fascination with ancient textiles from Mexico and Peru: a reflection of her ongoing interest in the history of weaving beyond the Western European tradition. Examples of her personal collection of Andean textiles include fragments of cotton, wool tunics, and tapestries, with some dating back to 600–1000 AD.

In these historical textile samples, figurative imagery of humans and animals are often mixed with the geometrically abstract patterns that frame them, which Albers worked into her own textiles. The woven silk, linen and wool piece Monte Albán (1936), one of the first pieces Albers made in the United States, is an example of the artist using the ancient weft technique in her work, enabling her to weave independent motifs into the fabric's main body.5 The piece is composed in earthy tones of grey and beige, with contouring lines and triangular edges moving through subtle transitions between dark and light created by intersecting threads. The textile's title comes from an archaeological site in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, with the 'cascading pyramidal and plateau-like forms' referring 'to features of the site'.6

Albers' engagement with architectural forms was another way to dismantle the existing borders between craft, fine art, and architecture. In her 1957 essay, The Pliable Plane, Albers argued that all primitive forms of architecture, such as tents and yurts, were based on textiles, and throughout her career she tried to connect textiles to architecture both practically and metaphorically. She made interior pieces like Camino Real for the Lobby Bar at Camino Real Hotel (1968) in Mexico City, designed by a close follower of Luis Barragán, architect Ricardo Legorreta Vilchis. For the bar, Albers produced a large-scale crimson tapestry that consists of small triangular elements building a larger pattern that references the Ziggurats, large structures of ancient Mesopotamia, and the Monte Albán archaeological site. A photograph of the work in situ, which Albers never saw in place herself, depicts a lively scene of clients drinking right next to it.

A series of textiles on display at K20, which the artist created in various collaborations with the design industry, included Melfi (1982–1983), designed for S-Collection Textiles: semi-transparent cotton intersected with white, zig-zagging patterns made from thicker fabric. Smaller samples shown in vitrines, featuring different geometric patterns in various colours on white backgrounds (Eclat, 1974), were designed for Knoll Textiles, who Albers worked with for over 30 years, starting in 1951.

Maze (c. 1982–1983) is a monumental textile commission: a transparent, three-metre-wide industrially produced polyester textile with a white, maze-like pattern printed on it. Designed for S-Collection Textiles, this is both a commercial product and work of art: an embodiment of the artist's lifelong ambition to integrate art, craft, design and manufacturing on a non-hierarchical plane. Like the exhibition that will soon open at Tate London, Maze is a testament to Albers' practice, and the ceaseless experimentation with new techniques and technologies that defined it. —[O]

1 Anni Albers, On Weaving, 1965.

2 Ann Coxon and Maria Muller Schareck, 'Anni Albers: A Many Sided Artist' in Anni Albers, ed. Ann Coxon, Briony Fer, Maria Muller Schaereck (Yale University Press: 2018), p. 14.

3 Anni Albers, 'Hand Weaving Today: Textile Work at Black Mountain College', The Weaver, Jan-Feb 1944, p.3.

4 See: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/222055

5 Ann Coxon, _'_Temple Commissions and Six Prayers' in Anni Albers, ed. Ann Coxon, Briony Fer, and Maria Muller Schareck (Yale University Press: 2018), p. 147.