APT8: A fragmenting vision of the future

It is 16 years since I last visited an Asia Pacific Triennial and it is heartening to see that although APT8 is a very different beast from the ground-breaking APTs of the 1990s, this edition has stayed true to the triennial’s philosophy of interacting with the region’s artists in a sustained and very localised way. When the APT was born in 1993 it was without doubt ahead of the curve. Although Australia’s engagement with the Asia-Pacific region was already a political and economic imperative, it certainly wasn’t a cultural one. In 1993 Asia was still perceived by Australia as on the periphery—and Asia felt the same way about Australia. Even today, Australia’s relationship with its immediate neighbours is a sometimes troubled and too-often neglected one. In the intervening years, the market for contemporary art has skyrocketed, and the market for contemporary Asian art, which barely existed 20 years ago, is also buoyant. On the non-profit side, museums and artist spaces, biennales and triennales, and, in general, opportunities for art to be seen, have proliferated. Similarly, the borders for contemporary art in the Asia-Pacific region have shifted. The Middle East is now a thriving market, and APT8 sees the introduction of artists from Mongolia, Nepal, the Kyrgyz Republic and Georgia. Of course the APT benefits from this growth, but it also has the potential to diminish the triennial’s prominence in what is a very crowded calendar for contemporary art and its associated events.

APT8’s focus is on performance, and therefore on the body. This idea allows the curatorial staff to go back to the seeds of the first triennials and to reference the exhibition’s history of engagement in this sphere. In Asia, particularly, the history of performance art is a chronicle of activism. The medium continues to require a government licence in Singapore, and to be viewed with suspicion by authoritarian governments in the region. Performance suits the APT’s activist bent. The APT, like APT8 participant, Australian Aboriginal artist Brook Andrew, seeks to interrupt both the white historical narrative and the Western art canon. Andrew’s Intervening Time, 2015, running over Queensland Art Gallery (QAG’s) Australian Colonial art galleries is not performance per se; but it is performative. Andrew has painted the traditional chevron pattern of the Wiradjuri people on the walls of the galleries in deep reds, purples and black, and then re-hung the colonial works along with his works from the series Time of 2012. The zigzagging pattern is disorienting and creates unease, invoking a history of neglect and omission. Andrew—like the APT—shows up the static, one-way process of looking at art. This work, and its dualistic title, offers a ground for the body of Aboriginal art and history and situates Aboriginal culture, which is often viewed as of the past, in the contemporary national narrative.

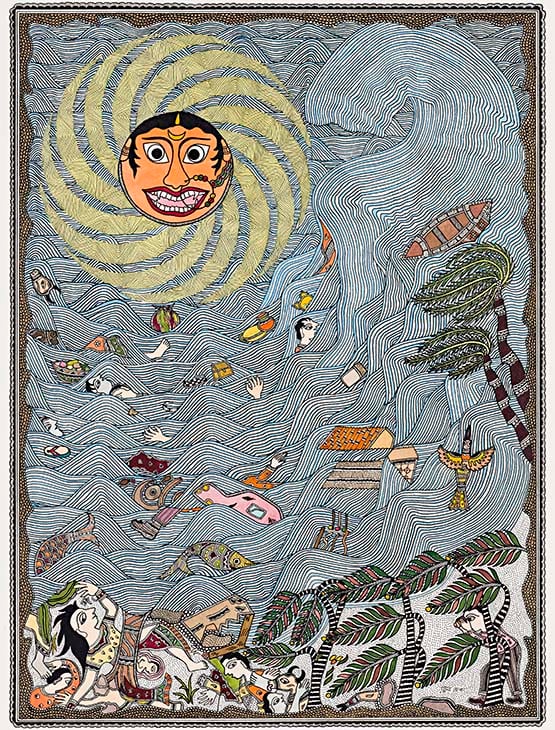

Image: Brook Andrew, Intervening Time, 2015, Exhibition view. Image courtesy Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. Performance is all about multiple interactions between the audience and the artist. It is also an art form of the now—the contemporary—but in many Pacific nations it is part of a social and cultural heritage. The idea of showing traditional cultural forms in a contemporary art context is not new, but it is something the APT pioneered. The APT has a history of introducing vernacular, tribal or village-based art that is undergoing a transformation. In this vein APT8 showcases the major project Kalpa Vriksha: Contemporary Indigenous and Vernacular Art of India. An earlier engagement with Indian artist Sonabai, whose clay figurines featured in APT3 in 1999, is revisited in the exhibited Rajwar sculpture of her son and several others. In these works, in the Kalighat painting of Kalam Patua, and in many of the other artists’ works here, there is an engagement with issues unique to the contemporary world, such as HIV AIDS and the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and evidence of new media and styles.

Pushpa Kumari, Tsunami, 2015, ink on acid-free paper 61 x 46cm. Purchased in 2015 with funds from Rick and Carolle Wilkinson through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery.The completion of the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in 2006 not only created the somewhat unattractive moniker QAGOMA, but also gave the APT the opportunity to move beyond the walls of the now-dated QAG building and become a fully fledged, international-standard contemporary art exhibition. But while the APT might be world class it is still very much a local show, and this character provides both the exhibition’s strength and weakness. In the early days of the exhibition, it would have been easy to disappear the ‘Pacific’ from the show’s title and to focus exclusively on the fast growing Asia region. Easy, but not particularly prescient. Despite its then underdeveloped contemporary art sector (with the exception of New Zealand), the loss of the Pacific would have been to the longer-term detriment of the APT. The triennial specifically works because it represents Australia’s peculiar and particular history of engagement and relationships with the region, and this must include the Pacific. The inclusion of the Pacific also allows Australia to participate in the exhibition, geographically. While the Pacific region continues to struggle with poverty, governance issues and with newer big problems like climate change, it is also producing confronting, unique contemporary art. Again, it is where artists draw on their local that APT is at its strongest.

Taloi Havini and Stuart Miller, Russel and the Panguna mine (from Blood Generation series) 2009, printed 2014, digital print on Canson Platine fibre rag paper, 310gsm, ed. 2/10 / 84 x 120cm. Purchased 2014. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery.Disappointingly, the home-grown nature of the APT does have ramifications, and the event continues to draw a mostly local crowd, with art industry and collector groups from Asia thin on the ground. This despite the fact that QAGOMA’s acquisition of many of the works commissioned by the APT means the institution has one of the world’s best collections of contemporary Asian and Pacific art. And it does capitalise on this by presenting exhibitions independent of the APT that draw on the collection and allow the institution to grow new audiences. QAGOMA has also established the Australian Centre of Asia Pacific Art (ACAPA) and has an extensive archive of material. APT8 sees the reintroduction of an accompanying conference, in this case run in conjunction with the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand (AAANZ). Add a film component and APT8 Kids and QAGOMA has it covered. But perhaps another explanation for audience profile might be that the idea of ‘Asia’ is fragmenting as the market becomes more sophisticated. After all, there are now enough art producers to allow the collector and the curator to focus purely on Chinese art, or Indian, or Indonesian, or, for that matter, contemporary ink painting. Nevertheless, the short history of the APT is that of contemporary Asian art; it was there at the beginning and holds an important place in this history, as does Australia’s engagement with it. Today the APT remains the only exhibition of its kind, and continues to be one of the most exciting offerings around for its 3 yearly snapshot of a region where big changes are happening everyday. —[O]

Taloi Havini and Stuart Miller, Russel and the Panguna mine (from Blood Generation series) 2009, printed 2014, digital print on Canson Platine fibre rag paper, 310gsm, ed. 2/10 / 84 x 120cm. Purchased 2014. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery.Disappointingly, the home-grown nature of the APT does have ramifications, and the event continues to draw a mostly local crowd, with art industry and collector groups from Asia thin on the ground. This despite the fact that QAGOMA’s acquisition of many of the works commissioned by the APT means the institution has one of the world’s best collections of contemporary Asian and Pacific art. And it does capitalise on this by presenting exhibitions independent of the APT that draw on the collection and allow the institution to grow new audiences. QAGOMA has also established the Australian Centre of Asia Pacific Art (ACAPA) and has an extensive archive of material. APT8 sees the reintroduction of an accompanying conference, in this case run in conjunction with the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand (AAANZ). Add a film component and APT8 Kids and QAGOMA has it covered. But perhaps another explanation for audience profile might be that the idea of ‘Asia’ is fragmenting as the market becomes more sophisticated. After all, there are now enough art producers to allow the collector and the curator to focus purely on Chinese art, or Indian, or Indonesian, or, for that matter, contemporary ink painting. Nevertheless, the short history of the APT is that of contemporary Asian art; it was there at the beginning and holds an important place in this history, as does Australia’s engagement with it. Today the APT remains the only exhibition of its kind, and continues to be one of the most exciting offerings around for its 3 yearly snapshot of a region where big changes are happening everyday. —[O]