Art Underground: An Ocula Report from Tehran

With the recent nuclear rapprochement, Iran is on the brink of the end of sanctions. This, along with new-found freedoms that arrived with the government of Hassan Rouhani in 2013, has fostered a sense of optimism. It seems a fortuitous time to visit and I am keen to see how the city’s artists are depicting this shift. Our trip has been organised by the Hong Kong-based Asia Art Archive and is the 2015 instalment of their yearly Collectors Circle trip. The Archive and London-based Iranian independent curator Leyla Fakhr have arranged the itinerary.

During our two days in Tehran, we visited Shirin Gallery, New Media Society, Ab/Anbar, Aaran Gallery, Assar Art Gallery, O Gallery, and Aun Gallery. We saw a range of artistic practice: photography, painting, installation, sculpture, film, and work from young, emerging, mid-career, and mature artists. While the scene is small and self-starting, it is vibrant. Friday night openings are very popular social events and many attend. The scene is almost entirely domestic, with some Mid-East artists exhibiting, but very few international artists. The exception to this being an exhibition we saw of international Abstract Expressionism at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art - the building itself an intriguing example of contemporary Iranian architecture, spiralling underground in a Guggenheim-esque fashion.

While the gallery circuit is very much an emerging scene, with most commercial galleries eight years old and less, they are filling the gaps left by a lack of opportunities and institutional/government support for artists. A number are fostering young artists and there is a collegiate, collaborative atmosphere between artists, as they help each other with installation and catalogues, and work together on projects. Everywhere we visit, remarkable individuals are investing their own money and time in building a local arts infrastructure.

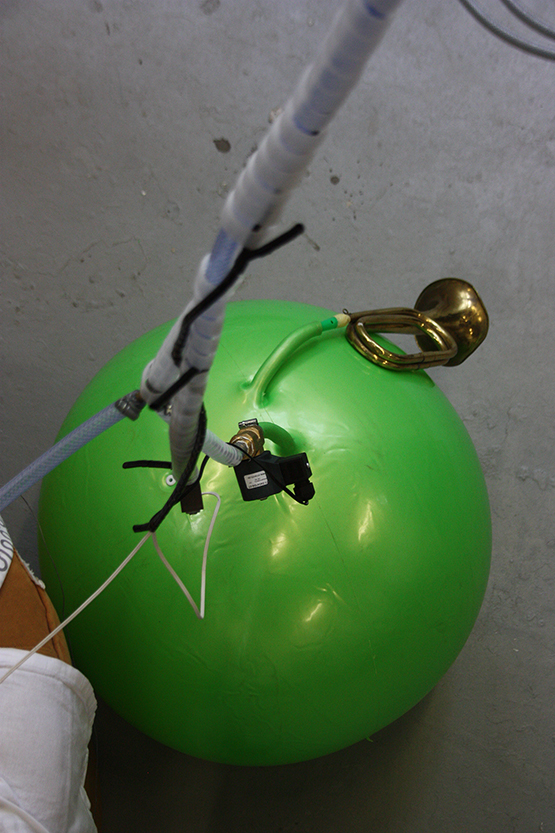

Mahmoud Bakhshi, Swiss Ball Climing up and Coming Down, 2015, Swiss ball, trumpet, solenoid valve, hose, compressed air, dimensions variable. Courtesy Ab/Anbar Gallery, Tehran.Ab/Anbar Gallery was showing an exhibition of work by Mahmoud Bakhshi and Arash Hanaei. Bakhshi is one of Iran’s best-known younger artists. He has been exhibiting internationally for a number of years and is currently represented in this year’s Venice Biennale exhibition The Great Game. He is also undertaking a 2-year residency at the Rijksakademie in The Netherlands. Bakhshi is a child of the Revolution and his work is inexorably tied to the life of his country. He often uses everyday, familiar symbols and objects in his work but imbues them with new pointed meaning. Swiss Ball Climbing Up and Coming Down, 2015, features a noisy trumpet attached to a green exercise ball that ascends and descends the gallery’s central staircase over 3 levels. As the ball is filled with air the trumpet blows loudly, insistently and without melody, quietening with the deflation of the ball. In the basement an air compressor powers the work. A tiring, annoying work it fulfils its aim, drawing attention with its noisy triumphalism.

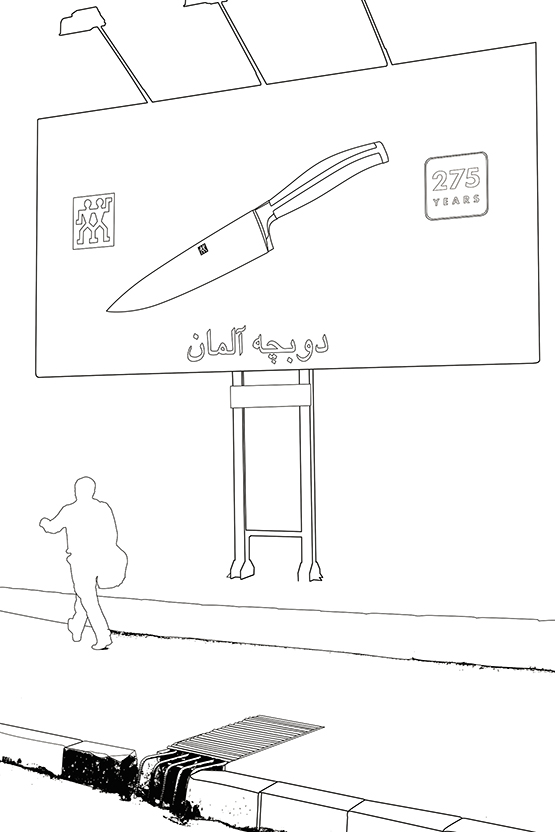

Arash Hanaei’s Capital series, 2015, sees photographic tableaus pared back to a graphic minimalist focus with the result that often one text or object within the scene is brought to the forefront. In singling out these often-banal objects, they acquire an importance and symbolism that go way beyond their intended purpose. At the same time our attention is drawn to their innate meaningless.

Arash Hanaei, Zwilling Germany, Capital Series, 2015. Pigmented inkjet print on Hahnemuhle rice paper, 165 x 110 cm, courtesy Ab/Anbar Gallery, Tehran.New Media Society is barely a year old, and is run out of a basic house in central Tehran. The Society doesn’t restrict the definition of new media to new technology-based work, but includes the reinterpretation of traditional media in this category. One of the society’s remits is to make a record of events and artworks that are produced by Iranian artists living overseas, in an attempt to reverse the effect of this flow of people and art out of the country. Perhaps this exodus is on the turn, as curator Leyla Fakhr tells me: ‘A large number of artists from the Iranian diaspora are increasingly keen to exhibit in their home country, perhaps to take part in the vibrant art scene or to re-identify with their country which is permanently in a state of flux. Tehran, in particular, is an environment that is hungry for art beyond the local and is as yet not over-commercialised or oversaturated, leaving plenty of room for voices to be heard.’ Clearly there are still challenges to be met at home if this trend is to be maintained. As New Media Society curator, artist and critic Zarvan Rouhbakhshan tells us, Iranian universities' art history syllabuses stop at the beginning of the 20th century. ‘It makes it easy for them’, he remarks, meaning, I think, that they do not have to deal with any of the challenges created by the social upheavals and new art movements of not only the 20th century, but also the 21st century.

At New Media Society we also met Bahar Samadi, a filmmaker, and Navid Salajegheh, an architect. As well as producing their own work, they work together as Studio 51. Samadi melds found home movie footage with historical images to create works that evoke a common shared memory.. We saw her film 101, 2012, a powerful visual of manipulated footage showing a confrontation in 2011 between Egyptian protesters and Mubarak’s forces. The film’s soundtrack features a woman’s voice counting in French. As the clashes with authorities intensify her counting becomes faster, louder and more insistent. There is a sense of a gathering groundswell and of the danger associated with change in the region. In Samadi’s flickering, hazy black and white film these recent and ongoing events seem to have already entered the historical canon.

Barbad Golshiri, The Untitled Tomb, 2012, iron, soot, 60.5 x 135 x 0.2 cm. Courtesy Aaran Gallery, Tehran.In the cool darkness of Aaran Project’s new subterranean gallery space, Barbad Golshiri’s Curriculum Mortis puts the artist’s convictions on the line and brings the wars and political struggles of the region uncomfortably close. He has filled the rooms with photographs, installations, video, and paintings, all related to death. In a room of photographs of graves from around the world, many are of the anonymous graves of those who opposed governments. For good measure, authorities often smash their gravestones. Another room features The Untitled Tomb, 2012, an iron stencil the artist has made for a man who was denied an engraved tombstone. The stenciled text is repeatedly reproduced in soot on the floor of the gallery, and smudged by visitors’ footsteps. When the family visits their relative’s grave they take the stencil along with them and, using the soot powder, they reproduce the text on his gravestone, temporarily granting him the identity he has been stripped of. Unwittingly, or otherwise, the family has become ongoing performers in Golshiri’s artwork, reigniting its power every time they perform this act.

Golshiri is also a gravestone maker, and his skill can be seen in the work Cenotaph of Arin Mirkan, 2014-15, which features a number of large stele-like stones crafted by the artist. Arin Mirkin was a Kurdish fighter who lost her life when she carried out a suicide attack on an ISIS post in 2014. The work will ultimately form Mirkin’s gravestone. Golshiri’s work is unusual for it’s real-world application, and his work appears to operate beyond the world of contemporary art, at the edge of the documentary genre.

Tehran’s basement gallery spaces provide respite from the extreme heat of summer. In a country—indeed a region—where religion dictates such a marked difference between public and private spaces, these spaces feel tucked away and private. The challenge for them and for Iran’s contemporary artists is to become part of the mainstream public life of the country. —[O]