Liverpool Biennial 2018: How to Make a Beautiful World

Mohamed Bourouissa, Resilience Garden (2018). Granby Gardening Club, April 2018, Liverpool Biennial 2018: Beautiful world, where are you? (14 July–28 October 2018). Courtesy Liverpool Biennial. Photo: Pete Car.

The Liverpool Biennial, which opened 14 July and runs to 28 October, is celebrating its tenth edition with a question. The show's title, Beautiful world, where are you?, comes from Friedrich Schiller's poetic work invoking the Greek gods, Die Götter Griechenlands, or The Gods of Greece. Written in 1788, Schiller's text was set to music by Franz Schubert in 1819, by which time the French Revolution and the fall of the Napoleonic empire had rocked Europe. Die Götter Griechenlands became a lament for a time of instability—a mourning that is echoed in the world today and the incessant stream of anxieties that plague it.

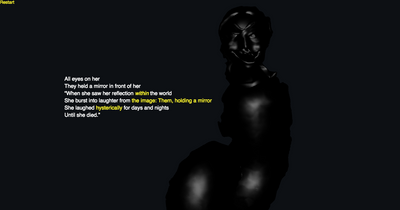

Drawing this history into the present, curators Sally Tallant and Kitty Scott have commissioned works by over 40 artists from 22 countries, which are presented in 16 historic and contemporary venues across the city. An online hypertext-based work by Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees The Unknown: The Laughing Snake (2018), can be viewed on the Biennial website; a collaboration with FACT and Whitney Museum of American Art.

As always, Liverpool's complicated ancestry as a dockside city that rose out of Britain's Imperial boom, is central to the exhibition's investigation overall. At Tate Liverpool, which resides in what was once a 19th-century warehouse within the Albert Dock, photographic imagery of quay cranes are collaged with folk imagery in Haegue Yang and Mike Carney's collaborative digital print, Dockside Rock and Roll (2018), which wraps around the entire interior of the ground-floor Wolfson Gallery. In the centre of the space, Yang's ongoing project The Intermediates (2015–ongoing) questions embodiments of folk traditions in the midst of this collaged industrial world: artificial straw weaves into fertility statue-like forms surrounded by plastic greenery, and woven ribbon designs ascend columns mimicking both the Maypoles of England and Saekdong—a traditional patchwork textile—of Korea (where Yang was born).

Upstairs, historical overlaps rooted in trade, industry, and conquest are brought out in Dale Harding's Wall Composition in Bimbird and Reckitt's Blue (2018). Reckitt's blue, a pigment used for whitening laundry up until the mid-20th century, has been applied directly to the gallery walls using the techniques of Aboriginal rock art. Harding's painting sees this specific blue pigment come full circle in this presentation—centuries ago, Reckitt's blue was transported to Harding's homeland, Australia, from ports like Liverpool to the workhouses of colonial settlements throughout the world, a reminder of Liverpool's place in support of the British Empire.

Much of the postcolonial critique on display seems to suggest that the beautiful world the Liverpool Biennial is searching for remains hidden or forgotten—in some cases, historically suppressed by imperialist structures that imposed their rule centuries ago. Positioned in front of Harding's wall painting are Brian Jungen's Warriors 1, 2, and 3 (2017): Native American style headdresses sculpted from the soles of sports shoes arranged in the centre of the space, mediating connections between past and present. Duane Linklater's installation The marks left behind (2014), a series of hanging skunk furs strung from metal clothing rails, is alcoved to the right of Jungen's work, serving as a reminder of Canada's colonial past and the fur trade's devastating impact on its indigenous people.

Drawing out a revolutionary angle to colonial history is Naeem Mohaiemen's marathon three-channel film installation Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), installed in the Crown Court room at the 19th-century neoclassical St George's Hall, which once functioned as a criminal court. The film carefully chronicles the various countries involved in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) during the Cold War period, with an emphasis on Bangladesh, Mohaiemen's home country, and its fight for independence from Pakistan, which was achieved in 1971. Through archival footage and interviews, Mohaiemen constructs a narrative that draws parallels between the liberation movements taking part across Africa, Asia, and Latin America at the time, while considering the implications of this ongoing history in the present.

At the Open Eye Gallery, Madiha Aijaz's documentary film installation These Silences Are All The Words (2017–2018) reflects on some of the reasons behind such struggles by exposing the gradual extinguishing of Urdu language and literature in favour of English, through conversations with librarians and library users in Pakistan. (In one example, the documentary tackles issues of censorship through the librarians of Ghalib library as they remove copies of Urdu poet Daag Dehlvi's work to avoid criticism from the academics who visit.) Unmasking the lasting impact of India's partitioning post-independence, the film touches on the difficulties in disentangling traditional culture from its colonial influences in our current globalised society; a theme that George Osodi's series 'Nigerian Monarchs' (2012–ongoing) continues in richly saturated photographs of regional rulers in the artist's home country. The composition of these photographic portraits gesture towards resilience and subversion through the means of self-representation. Men and women are composed in studio settings, their dignified poses reminiscent of neoclassical portraiture, and the intricate beadwork and lush fabrics of their clothing alongside the loyal servants crouched around them.

Taking into account the other side of the colonial condition is Mathias Poledna's new film Indifference (2018), entombed in The Oratory, a 19th-century building originally designed for funeral services adjacent to Liverpool's Anglican Cathedral. Framed by the century-old busts and relics that perch on the interior walls, Poledna's film depicts a soldier dressed similarly to the French Imperial guard, who moves, slowly and forlornly, from his seat at a restaurant to an exterior walkway. A dramatic orchestral soundtrack charts the man's movements until he falls down dead at just about the six-minute mark, when the film loops back to the start and plays again. The tragedy of the work resonates with the conditions in Europe today, as it seemingly stumbles into a future shaped out of its own past.

But the Liverpool Biennial does offer some productive responses to these historical inheritances. A short walk from The Oratory is Blackburne House, a charity centre which focuses on educating and empowering women. On view here is Taus Makhacheva's ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) Spa (2018), which extends the function of the House as a wellness centre for abused women. Staged like a room in a wellness centre, Makhacheva makes use of the online ASMR phenomenon, which has grown popular in the past decade, in which actors employ high definition speakers to re-stage calming or relaxing scenes defined by an acute focus on audio triggers, such as a trip to a hair salon, for instance, in which a practitioner will re-create the sounds associated with the space, such as brushing hair. Makhacheva's version utilises performers who apply facials to participants lying on a marble slab apparently repurposed from a statue that once guarded the building's entrance, while whispering stories of forgotten and lost artworks, such as Frida Kahlo's The Wounded Table (1940). The work explores mirror-touch synesthesia, a medical condition that allows people to experience other's sensations, embrace empathy, and bring about healing through it.

Another form of empathetic exchange is demonstrated in Rehana Zaman's film How Does an Invisible Boy Disappear? (2018), a reflection on racial and gender identities in Liverpool that the artist produced with a group of young Somali and Pakistani-Liverpudlian women. Shown in three parts, the film tells the story of a teenage boy who goes missing, and the young women who rally to find him; it also documents the establishment of a film co-operative by Zaman and the young women she worked with, which will outlast the exhibition's run.

Blackburne House's proximity to St James Gardens feels especially poignant. Buried there is Edward Rushton, an 18th-century poet and campaigner for the abolishment of the slave trade, a movement that started in Liverpool in the late 1700s. The grounds back onto Toxteth, a neighbourhood close to the city's once-thriving docks, where the 1981 Toxteth riots against racist and classist policies upheld by the government and local police took place. Decades on, Granby—the starting site of these riots—is home to a number of social movements and enterprises that continue Toxteth's ethos of community action, including the Granby 4 Streets Community Land Trust, which lobbies 'for affordable housing for shared ownership and affordable rent'.1

It is in this neighbourhood that Mohamed Bourouissa spent several months working with students, locals, gardeners, and teachers to produce Resilience Garden (2018): a greenhouse and garden constructed next to Kingsley Community School, which incorporates local greenery and plants from Algeria. Bourouissa was inspired by the revolutionary psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon, whose work explored the impact of colonialism on those who experienced it, and one of his patients, Bourlem Mohamed, who created a garden during his time at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Blida, Algeria. At FACT, where Agnès Varda's Liverpool Biennial commission, 3 moving images. 3 rhythms. 3 sounds (2018) consists of edits from Varda's films Documenteur (1981), Vagabond (1985) and The Gleaners (2000), Bourouissa presents the single-channel video-installation Le murmure des fantômes (The whispering of ghosts) (2018), in which Bourlem Mohamed talks, about Algeria's fight for independence, his bitter memories of the French, and survival as a form of revenge.

In this edition of the Liverpool Biennial, testimonies demand a degree of accountability, not least an openness to other historical and cultural perspectives. Each venue communicates a story of regeneration and resilience—none louder than Bourouissa's community garden, where genuine growth, with all its challenges, feels practically possible—even if the context of the city ensures that such optimism is tempered with stark realism. (The recent removal by unknown perpetrators of Banu Cennetoğlu's list of 34,361 documented deaths of asylum seekers, refugees, and migrants within the borders of Europe since 1993 from a Great George Street wall being a case in point.) What this tenth edition of Liverpool's Biennial demonstrates is that art can be utilised as a tool to share histories, traditions, cultures, and experiences while developing new ways of being in the process. By that chemistry, a beautiful world may well come into view.—[O]

—