Looping The Loop: Reflecting On Art Basel In Basel

Another year, another three Art Basels, and Art Basel’s home edition opened as if the boom days Hans Mayer recalled in a story about a Paladino painting passing hands four times in a few hours—increasing its value by five—had returned. “She’s literally remaking the readymade,” one gallerist gushed, as if looping a loop. The new layout enhanced the buzz: Magazines moved to Hall 1 to join Art Unlimited, and the Statements sector joined Galleries in Hall 2—a welcome move given the commercial advantage the switch provided for participating Statements gallerists. A positive blend, if you will.

And another blending took place, this year, too, as articulated at Art Unlimited in Xu Zhen’s monumental installation, Eternity… (2013/14): a scale reproduction of the Parthenon’s east pediment connected to upside down sculptures of various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas from the Northern Qi and Tang Dynasties. The piece, presented by Long March Space (Xu Zhen also showed with Nathalie Obadia, Vitamin Creative Space and ShanghART), illustrated The Art Newspaper’s front-page proclamation on preview day 2: “Now East meets West.” The article explained that, despite there being fewer Asian galleries this year (21 out of the 285, with 34 countries in total represented), more western galleries are showing Asian artists.

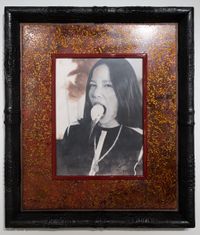

Correct enough. In the Galleries sector, McCaffrey Fine Art, presenting Richard Nonas at Art Unlimited, showed an excellent selection of works by Noriyuki Haraguchi, Sadamasa Motonaga, Jiro Takamatsu, Tatsuo Ikeda and Kazuo Shiraga, who also showed at Georg Nothelfer and Dominique Levy, with Taka Ishii Gallery presenting photographs of Shiraga at work by Kiyoji Otsuji. But the trend (or blend) went both ways: SCAI the Bathhouse presented works by Darren Almond alongside a selection of its regular roster—including Lee Ufan, Yosuke Komute and Kohei Nawa.

But what is at stake in this cultural meeting? Maybe what Long March Space Director Theresa Liang in The Art Newspaper noted when discussing the gallery’s excellent solo booth of works by Liu Wei: “You don’t need to know the historical or political context of the country to appreciate the works.”

This is of course a contentious statement. Especially when considering the common view of the art fair as a homogenizing space, which results in observations like one the director of a prominent European institution made of the fair this year while pointing to the fact that the market was dominating aesthetics: “everything is starting to look the same.” These sentiments recall Kimberly Bradley’s reflections on this year’s 8th Berlin Biennale: that an attempt to pull the biennial “out of its longstanding east-west narrative” resulted in an exhibition of what J.J. Charlesworth terms “art world Esperanto”— as Bradley explains, “artistic production operat[ing] on a visual lingua franca that no longer reflects cultural specificity or locality.”

Yet, though there are truths to such views as those of Jerry Saltz—whose hatred for bad (repetitive, derivative) abstraction was recently expressed in a Vulture diatribe—does everything really look the same? Has Art Basel’s cloning of itself led to a cloning of the aesthetics seen within it? Despite the wonderful works you might find at the fair—such as those by artists in Berinson’s outstanding historical selection, from Hannah Höch, Meret Oppenheim, Max Ernst (dotted throughout the fair), Frederick Kann, Carl Buchheister and Erich Comeriner, or in Thomas Zander’s excellent collection of photographic and video works—have we reached some kind of telos?

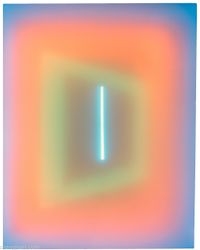

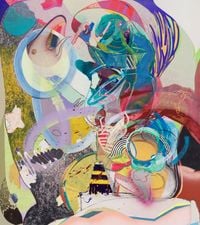

Not quite. Take these artists from various regions and generations who work with abstraction: Ivan Serpa (showing at Barbara Mathes); Eduardo Terrazas (showing at Proyectos Monclova, Almine Rech Gallery and Nils Stark); Jean Xceron (at Washburn Gallery); Almir Alvignier (at Berinson); Camille Graeser, Beat Zoderer, Auguste Herbin and Andrew Bick (included in Von Bartha’s fantastic booth); Lesley Vance (at Xavier Hukfens); Ben Nicholson, Ivan Kilun and Alexander Exter (at Annely Juda Fine Art); Julian Stanczak (Mitchel-Innes & Nash); Albrecht Schnider (at Galerie Thomas Schulte and Bob Van Orsouw); or Willi Baumeister, presented by Galerie Klaus Gerrit Friese in the Features sector and Shinro Ohtake, presented at Take Ninagawa also in Features. Then there were Rita Ackermann’s three large-scale chalkboard paintings in Unlimited: A Study on the Aesthetic of Disappearance – Hair Wash (2014), which collectively stood, as explained in one text, “as a monument to movement as opposed to any narrative story or lecture.”

In each case, the artist has applied languages and concerns produced from manifold sources, bringing us back to Liang’s statement on Liu Wei’s work, and the assertion that it is better to know the artist first and start from there.

In this sense, Liang’s quote would be better read in relation to the approach Cameroonian artist Pascale Marthine Tayou took for a sprawling Christoph Büchel/Kader Attia-esque Unlimited installation, Tayouwood (2014), which suggested that, rather than knowing the country or the context, one had to look to the artist. A maze-like construction designed to resemble Tayou’s hometown, and framing an internal curation of video and assemblage, the text describing the work explained: “The objects produced by Tayou share a common denominator: they dwell upon the individual moving through the world, exploring the global village.”

And if the art world is a global village, Art Basel is its market square: a place that—for its individuals—could well feel like the subjective space Kazuo Shiraga described in a wall text at Dominique Levy when talking about how he wanted to paint: “as though rushing through a battlefield, exerting myself to collapse from exhaustion.”

Indeed, presenting multiple worldviews that overlap, diverge, and at times dominate, Art Basel is a battlefield (Matias Faldbakken’s Unlimited installation invited viewers to walk on gun shells). A place where conflicting, parallel and complementary desires and narratives—personal and collective, local and global—collide, and it can be exhausting. It is an art fair that invokes Arjun Appadurai’s observation that today there are fewer cultures and more internal cultural debates: where the “East-West” (or “North-South”) narrative might be read on more fluid, universal terms, like the spectrum produced at Cheim&Read between Jack Pierson’s 2014 wall text “FREE LOVE” and Jenny Holzer’s 2006 marble footstool inscribed with the statement: “THE BEGINNING OF THE WAR WILL BE SECRET.”

Culture, after all, can so often lead to conflict. And market culture can ignore conflict altogether (or capitalize on it). This report, after all, does not even go into the other issues within the fair space, like the Yang Fudong vs. Ming Wong showdown on gender representation in Unlimited, or to the artist rosters that led one visitor to tweet on Art Basel’s gender #fail.

But conflict is not confrontation. In Mikhael Subotzky’s Unlimited work, Moses and Griffiths (2012), a four-channel video installation focuses on a small city in Grahamstown, South Africa, through interviews with Moses Lamani, who gives tours of the Observatory Museum’s camera obscura, and Griffiths Sokueka, who gives tours of the 1820s Settlers Monument. The video edits both the official tours the men present as Subotzky describes, “by rote,” and the personal accounts offered upon the artist’s request. Presented in the round with each recorded account cutting and splicing into the other, the result is a chaotic confrontation. Placed firmly at the centre of this meta landscape, the viewer is not necessarily challenged to respond to the portrayal of the lives of others and the histories such lives are embedded in, but rather bear witness to the testimonies, at least.

This tactic was also palpable in Santiago Sierra’s 14 Rooms installation—an exhibition of performance art curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach—with a title that said it all: Veterans of the Wars of Afghanistan, Timor-Leste, Iraq and Vietnam Facing the Corner (2013). The work acted like a mirror: implicating the viewer-as-voyeur while underscoring the detachment from others that comes with distance and privilege, not to mention spectacle.

14 Rooms drew mixed reviews. One performance artist took issue with the corporate nature of the presentation, noting how the exhibition exemplified just how far removed the art world is from the world right now. Such whispers echoed on the fair floor, and were reflected in works like Alfredo Jaar’s 1995 neon text piece Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness shown at Galerie Thomas Schulte’s excellent booth alongside—amongst other works—an installation by Michael Müller: the K4 Archiv (1995–2014). In this, a taxidermy scarlet ibis on a pedestal gazes at a framed image of itself like a mirror, in turn surrounded by the artist’s translation of Robert Musil’s novel The Man without Qualities into his own system of character-codes. Fittingly, Müller has a solo show on at Thomas Schulte to July 26 titled: What is considered art? What does it mean to be true to oneself?

This idea of a search—for new knowledge, better qualities, an identity that fits the art world’s clusterfuck—was articulated in a number of works this year, all employing the book as a readymade material, including, amongst other examples: Hassan Sharif at gb agency; Richard Wentworth’s dictionary stuffed with found materials at Peter Freeman; Peter Wuethrich’s beautiful geometric compositions using coloured books for blocks at Galerie Alice Paul; and Liu Ye’s Book Painting No 2 at Johnen Galerie, also featuring Roman Ondák’s used cans covered with book titles for labels: Ulysses, Pathology and Surgery (all 1995) presented on a bookshelf.

OMR showed Jose Dávila’s The Origins of Drawing, 2014: a series of archival book pages blocked out by gold leaf. On one page the title “THE CHILDHOOD OF ART” was printed over a gold rectangle, below which the caption described the blocked out image as: ”an outline of a rhinoceros chipped out of stone by South African Bushmen,” located by a “Dr. Holub,” to “their most primitive stage.” Here, the interpretation of visual culture is coupled with uncomfortable colonial (or utopian?) undertones: a kind of tyranny of knowledge (here linked to empire building) that added extra punch to Julieta Aranda’s A Machine for Perpetual Possibility: a 2008 work presenting the dust of pulverized science fiction from before 2007 in a Perspex box, occasionally puffed about by an air compressor. Such tyranny also reflects on judgments levelled on art through a consideration of where it came from, rather than what the artist was actually thinking through.

So why all the books? At Unlimited, Hanne Darboven and Ryan Gander provided some insight. Darboven’s Kinder dieser Welt (Children of this World) (1990–1996) was a sprawling installation of childhood memorabilia—kindergarten books, old toys, models and dolls—as well as some 2,134 framed pages containing charts, calculations and other notes on a musical score by the artist. Produced in the aftermath of German reunification and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the exhibition text described the work as one that makes “apparent the thought patterns of a possible ‘restart’ in history.”

This chimed well with Gander’s Imagineering (2013): a series of TV advertisements that form a campaign Gander designed and then commissioned promoting imagination in the UK public and produced in the style of the British government’s Department for Business, Innovations and Skills. The advertisements called for “daydreamers,” and was also featured in poster form under the title Make Everything Like It’s Your Last, as part of Florence Derieux’s stand-out Parcours programme this year, which fitted works seamlessly into the city, from Chris Burden’s public sculpture comprising of four iron benches forming a square with cast-iron lamps at each corner (Holmby Hills Light Folly, 2012), to Jean-Luc Blanc’s haunting canvas Un peu etriot (2014), shown in the shop window of a 14th Century craftsman’s house, to the inclusion of composed music by Seth Price in various locations.

As in Derieux’s Parcours, Gander’s project posited art and knowledge production as an act of play: a whimsical and wonderful thing that makes the impossible seem possible. In essence, his advertisements were a call for a refresh—a reminder that the willingness to approach the world with new eyes and imagine new things is something we all had, once. Just as the nostalgia for childhood in Darboven’s installation reflected on a loss that could be regained, or overcome: A looping of a different loop, from an end to a beginning. —[O]