One belt, one road, one biennale: Yinchuan's stand against cultural desertification

Yoko Ono, Exit (2016). Dimensions Variable, 100 coffins, plants and trees. Courtesy Yinchuan Biennale.

Over 70 artists from 33 countries are represented in the inaugural Yinchuan Biennale, which opened amidst scandal on 9 September 2016. Not included is a work by Ai Weiwei, who was invited to take part alongside other art stars Yoko Ono and Anish Kapoor before being disinvited just weeks before the opening.

In a tweet, Ai connects the decision of 'higher officials' not to include him to sensitivities surrounding the 'One Belt, One Road' policy, which aims to build economic and political ties between China and countries to its north and west (the Silk Road Economic Belt) and countries from Southeast Asia to East Africa (the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road). The ensuing scandal has somewhat dimmed the wattage of the soft power project.

Were it not for the policy, it's hard to imagine the Yinchuan Biennale existing at all. Located in Ningxia province, on the old Silk Road between Beijing and Xinjiang, Yinchuan is a city of roughly 2 million people, better known for goji berries and its Sand Lake scenic spot than contemporary art. By my own measure of a Chinese city's development—the number of three wheeled cars still on the roads—Yinchuan is a long way behind Shanghai and Shenzhen.

Yet since 2015 it has been home to China's second ever state run contemporary art museum, a secular cathedral designed by Britain's waa (we architech anonymous) to suggest the shifting sediment of the nearby Yellow River. For now, it's quiet. Located in wetlands half an hour from the city, artistic director Hsieh Suchen says as few as four people a day come through the museum during heavy winter snowfalls. But the museum is looking ahead to a future when the ancient Silk Road, once the major trade route connecting China to Europe and Africa, is again a thriving economic and cultural corridor.

For his part, Ai had planned to exhibit a steel sculpture inspired by a photograph he received from the exhibition organisers. The picture was marked with a digitally drawn red line showing the area outside the museum where he would be allowed to place his art. 'Redline', modeled on the mark, would have been emblematic of the numerous times Ai has overstepped the Chinese Communist Party's invisible red lines and the limited spaces in which he is permitted to pursue his practice.

In late August, however, it is reported that Ai received a cryptic lyrical message from Hsieh on behalf of herself and biennale curator Bose Krishnamachari: 'Bose and I invited you to participate in this year's Yinchuan Biennale because we sincerely admire your artwork. But things change in this world. Even though your project is full of philosophical awareness, an artist's prestige overshadows his work. The autumn wind is blowing around us. The museum has no choice but to rescind its invitation to you.'

Kapoor contemplated withdrawing from the show in solidarity with Ai, but his towering self-generating crimson wax sculpture Untitled (Bell) (2010) was installed when the exhibition opened. Mary Ellen Caroll's This Time With Jacky, Look Far Away (2016)—five red flags stretched taught over the full height of the museum's exterior—was a better apology for the absence of 'Redline'.

Krishnamachari, co-founder of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (along with Riyas Komu, whose work You Made Me a Communist (2016) appears in the exhibition), appears to be alluding to the red and crimson controversy in a passage introducing the exhibition. Artworks, he says, 'may propel us across the Red Line of restrictions: economic, political, social and ecological. Seek the spiritual as we Think the Unthinkable and Do the Impossible. Create a new Thin Red Line along the humbling silhouette of the Helan mountains where Hope floats ... ∞'

Even without the predictable exclusion of Ai's work—a brave effort by the organisers nonetheless—the Yinchuan Biennale has set itself a challenging task. Krishnamachari has described the exhibition in traffic light colours, alluding to communism and Islam as 'Red, a state of dominance, and Green, a state of acceptance', with Yinchuan on the Yellow River, at 'the fault line of these two colours'.

China's relationship with Islam is not as hysterical as it is in French and American politics, but nor is it straightforward. Uighurs, a Muslim minority from Xinjiang Province, face widespread suspicion and discrimination, and a colleague of mine, whose mother is a Hui Muslim, says Han Chinese have asked her why Muslims worship pigs.

Yinchuan is the capital of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR), home to a large portion of China's 20 million Muslims. Yet Chinese Muslims (admittedly only two per cent of the population) are invisible in the Yinchuan Biennale, as they are in the broader Chinese contemporary art scene.

Only one participating artist, Mao Tong Qiang, comes from Ningxia. His work 15 Decibel (2016) is an abandoned KTV room in which a Mao-era propaganda song plays on loop, a thick layer of grey dust over everything suggesting—a little prematurely—that it's all ancient history.

For the most part, Chinese artists participating in the exhibition are less interested in the country's Maoist past or the intersection of Islam and communism than China's high cultural and technological churn rate. Cao Fei's wonderfully wacky video Rumba II: Nomad (2015) sees robot vacuum cleaners struggle to steer toy chickens around demolished buildings; Liu Wei's China III (2006) is a rocket assembled from readymade ceramic vases; and Li Jinghu, who lives in the factory city of Dongguan, arranges cell phones vertically, connecting different videos of falling water playing on each to make a single, manufactured waterfall.

Most pertinent to the biennale's themes is Song Dong's_Through the Wall_ (2016), a bus-sized installation made of found doors and windows that opens at either end to reveal an exaltation of densely packed framed mirrors and a blazing ceiling of hanging lamps. The work is based on the idea of spirit walls, which allow people to enter and exit while keeping out evil spirits, incapable, for some reason, of turning corners. Of course, contemporary China and Islam have their own walls that are permeable to some and impermeable to others.

Though it's not part of the work she's exhibiting at the biennale, I spoke to British artist Abigail Reynolds in Yinchuan about her project visiting the sites of lost libraries along the ancient Silk Road from Xi'an to Italy, connecting the dots between the destructions of conquering Roman empires, Chinese dynasties, the Cultural Revolution and the contemporary aggressions of ISIS. It promises to be a marvelous commentary on hostility towards knowledge, communication and commentary itself.

Molla Nasreddin the Antimodern (2012) is another of the few works that really resonates in Yinchuan. Known from Morocco to Central Asia, India and China, Nasreddin is a white-bearded folk figure, both wise and foolish, who's often depicted riding backwards on a donkey. The version at the biennale, created by the Slavs and Tatars collective, is perfect: a ride on toy—ubiquitous in China—that serves as edutainment, a fair description of biennales in general, but especially those allowed to take place in authoritarian states.

Perhaps a Chinese curator would have made more connections between Islam and Chinese culture, but Krishnamachari has indubitably contributed to the biennale's distinct identity, and the 'One Belt, One Road' objectives, by including many artists from the Middle East and South and Southeast Asia.

Overtly Muslim works include: Ammar Al Attar's 24 Salah Movement, which depicts prayer as if it's a series of yoga poses; Saudi artist Dana Awartani's geometric patterns; and Hassan Sharif's wonderful White Knots (2015), Black Knots (2015), Pink Knots (2015), shaggy rope works he created in a process he described as 'weaving'. (Sharif passed away just ten days after the exhibition's opening ceremony.)

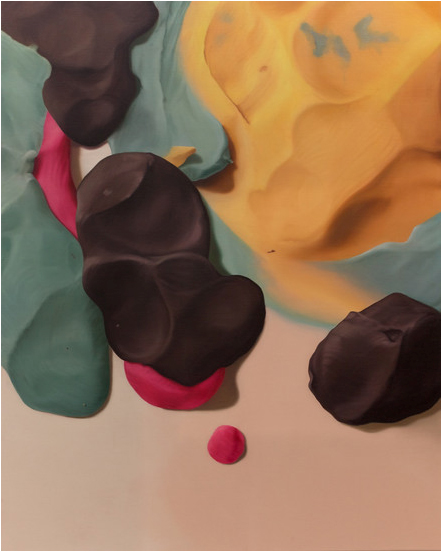

Impressive works from South Asia include: Dia Mehta Bhupal's Trolley (2016) and Pharmacy (2016), photographs of 3D sets made with magazines, newspaper and cardboard; and Benitha Perciyal's fragrant, fragile wall of incense, Me a Woman, My Thoughts a Thousand (2016).

And yet, while the biennale includes artist from Tunisia and Tehran, Sydney and Syria, Dubai and Delhi, Myanmar and Mysore, Kathmandu and Kota Kinabalu, there's something disingenuous about a monoculture that's increasingly hostile towards foreign culture, foreign residents, and foreign businesses hosting international biennales.

With the transparency that's so integral to his practice, Ai went public with the news of his exclusion from the Yinchuan Biennale, writing on Instagram that 'what we face is a world which is divided and segregated by ideology, and art is used merely as a decoration for political agendas in certain societies. China is trying to develop into a modern society without freedom of speech, but without political arguments involving higher aesthetic morals and philosophies, art is only served as a puppet of fake cultural efforts.'

Robert Montgomery, exhibiting total disregard for the flat, landlocked landscape of Yinchuan but genuine sensitivity to the insidiousness of 'fake cultural efforts', created the largest, longest, most prominent work in the exhibition. The LED text of Wipe Your Tapes With Lightning (Poem for Paul Reekie) (2016), which is displayed on a bridge extending across the pond in front of the museum, reads, 'THE BIRDS RETURN WITH UN-VIDEO-TAPED MEMORIES OF THE MOUNTAINS. THE SEA HAS NO NAME FOR CHINA OR AMERICA. THE SEA HAS NO NAME FOR EVEN ITSELF'. —[O]