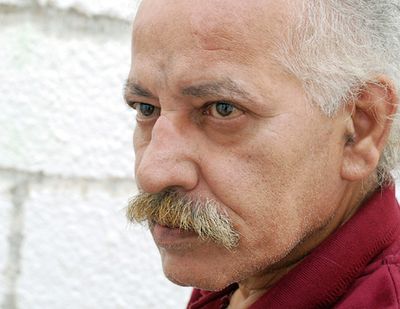

Hassan Sharif

Hassan Sharif. Image courtesy the artist

Hassan Sharif. Image courtesy the artist

Hassan Sharif lives and works in Dubai. He has made a vital contribution to conceptual art and experimental practice in the Middle East through 40 years of performances, installations, drawing, painting, and assemblage.

In his early artistic maturation, Sharif rejected calligraphic abstraction, which was becoming the predominant art discourse in the region in the 1970s. Instead, he pursued a pointedly different art vocabulary, drawing on the non-elitism and 'intermedia' of Fluxus and the potential in British Constructivism's systemic processes of making.

Sharif graduated from the Byam Shaw School of Art, London, in 1984 and returned to the UAE shortly after.

He set about staging artistic interventions and the first exhibitions of contemporary art in Sharjah, as well as translating art historical texts and manifestos into Arabic, so as to provoke a local audience into engaging with contemporary art discourse.

In addition to his own practice, Sharif has encouraged and supported several generations of artists in the Emirates.

He is a founding member of the Emirates Fine Art Society (founded 1980) and of the Art Atelier in the Youth Theatre and Arts, Dubai (founded 1987). In 2007, he was one of four artists to establish The Flying House, a Dubai institution for promoting contemporary Emirati artists.

In this conversation between Hassan Sharif and Anabelle de Gersigny, the artist discusses his approach to new works for his recent exhibition at Isabelle van den Eynde and his participation in the UAE Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale. The conversation includes an exploration of the artist's thoughts on consumerism, art as a social practice, notions of identity and national identity and the role of artists in the UAE.

Images are there to stimulate people in our current consumerist society, or perhaps that was always their function.

AGI'd like to start with your recent exhibition at Isabelle van den Eynde (which closed 5 May 2015). You included a broad range of work, from projects that were started in London in the 1980s to more recent pieces. It was interesting to see your story folding back on itself, in a kind of reflection and re-purposing of methods and concepts. What were your intentions with this exhibition, in terms of this approach of bringing older works to the fore?

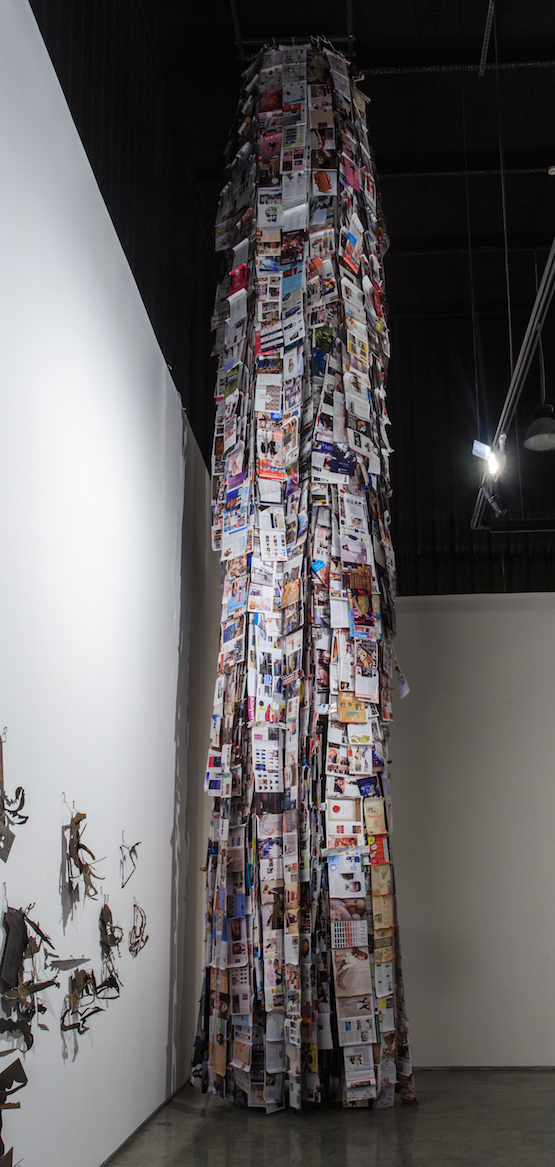

HSI've been working on the project I call Images for three years now. It wasn't something I worked on all the time, but images that I referred back to and would store, till they were ready for exhibiting. The underlying concept to the new works is related to the proliferation of images in our contemporary world.

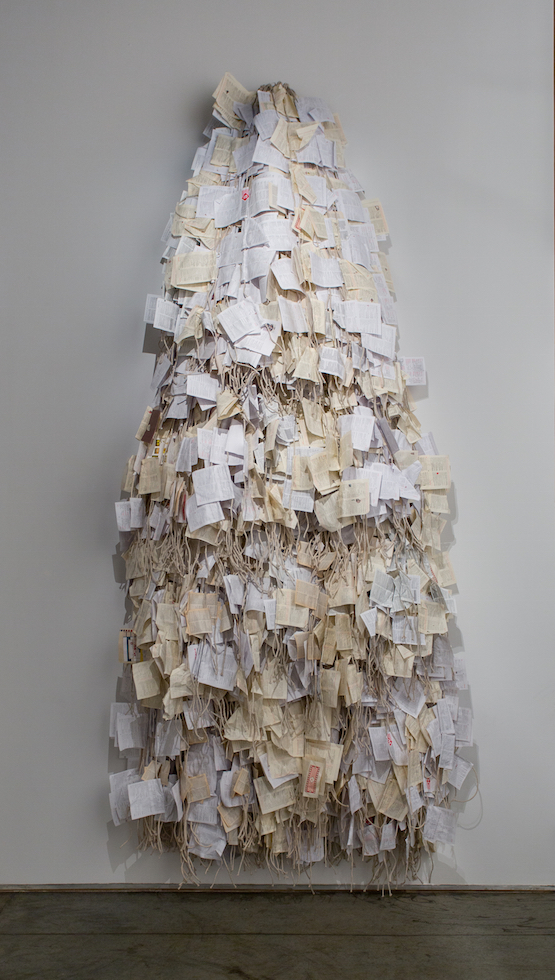

Images, particularly photographic, are everywhere—constant and yet ephemeral like ghosts. They are fast, often coming from distant places, and coming from a number of sources: the computer, TV, even the radio. Sounds become images that you hear, for example if I say the word 'apple', you immediately imagine the fruit or the company. My Dictionary pieces stemmed from that—I used about seven illustrated dictionaries, both English and Arabic—one being a dictionary I used when I was at art college in London in the eighties.

When I went to study in London, I was told that if I didn't learn English, I would not be able to access the information and knowledge required to work conceptually—something I retaliated against and the Dictionary piece is a play on that. So, I use anything from the illustrated dictionary to printed t-shirts.

AGIt's interesting to think about language in that way too: that access is restricted to the language you speak, even in the visual arts. How did you then, and how do you now, transcend these barriers?

HSImages are there to stimulate people in our current consumerist society, or perhaps that was always their function. But images can also provoke people. We can see it in the shopping mall. The malls are an important social vehicle in the UAE and everything in the mall is there to stimulate us. It's a post-modernist existence, and I think of post-modernism as something horizontal, like the multipliant species of trees, for example mangroves, that grow laterally as much as vertically, their branches dipping into the ground and initiating new roots.

AGIt's interesting you say that, because they also often create big shelters for communities, under the interconnected canopies. Do you see this canopy of images in some way as holding back and containing communities and social structures?

HSYes, they make colonies, reinforcing themselves against each other. Similarly, if you cut a branch and plant it, it starts to grow again. It's a bit like the recycled material I receive on my doorstep, day in and day out, advertising papers; I've collected all these over the years and then used them in this project. I didn't want to throw them away, because each image was its own form of communication: for example, the supermarket brochures, with the prices of items listed.

It's like a printed shopping window, the seduction of that framed space in print. I imagine people standing in front of the shop window, they can see a reflection of themselves in the glass, whilst they simultaneously see the reflection of other people passing, coming and going, and all they can think about is this thing that they want inside. They make comparisons of themselves to the others around them. They start to believe that these things will make them more themselves than anything else.

Through this work, I am saying, 'These are the images I am subjected to. What are yours? Do you recognise yourself in these?'

This person goes inside, he or she wants to touch the unreachable. The sales person asks them what they would like, how they can help, and they point to the object, ask the price, and decide to buy it. So as soon as they've paid, they believe that they are getting something—that they are in a better spot than they were before. But actually, they're losing something vital—his or her own hold over their identity. This is consumer capitalism and it is a sickness.

If you drive down Sheikh Zayed Road, there are massive billboards all the way along it. I like to look at these, to watch them change every month or so, they are like those mirrored sunglasses. You stare out through a filter, and the thing in front of you is yourself; each image holds the potential of a new self. This is everywhere, not just the UAE, but perhaps here the billboards are more present or numerous than in other cities.

So there is this cycle, you work in order to buy, you spend and then you need to work again. I don't criticise this per se, but I am keen to show or remind viewers that this is now our reality. Through this work, I am saying, 'These are the images I am subjected to. What are yours? Do you recognise yourself in these?'

AGAs objects, that stand independently, that reflect on these notions of mass consumerism, of the realities of capitalism, do you imagine the viewer placing or finding themselves somewhere within these objects? For example, the younger generation of artists—where do you hope or imagine they position themselves and what do you hope they draw from these pieces, particularly from the perspective of comments on current societal states?

HSThere are a number of artists doing very well in the UAE at the moment: Ebtisam Abdul Aziz, Nasir Nasrallah, Abdullah Al Saadi and Shaikha Al Mazrou among many others. They are not just making conventional works of art, but they are committed to seeking out new areas, to drawing on conceptual approaches.

I see this consumerist future as something that is forcing itself on us, and it is really important that the younger generation of artists realise this and think laterally about how to perhaps deviate, how to interpret. Again, I see this as a horizontal approach as opposed to the vertical.

If we use the city landscape as an example—on a physical level this city is growing as much vertically (in terms of architecture) as it is horizontally (culturally), but one is not more important than the other. The future may be heading in one direction (a focus on the vertical and prolific construction), but this does not diminish the importance of the horizontal activities. There is a quote by Andy Warhol when he was making his Mona Lisa prints; he said that multiple Mona Lisas were better than one, so from one silk screen, he created 30 [images].

Accumulation becomes important, stacking one thing on the other. It's like time—the idea that history stacks itself one event on another. By taking elements from the world around me, I repurpose them, restack them and present a different way of reading the situation. My practice insists [on] and requires this process. This also involves a recycling of concepts and approaches, for example British Constructivism; art as a practice for social purposes.

My intention is to stimulate society, the viewer, in order to understand the foundations of contemporary or modern art and to understand or engage with the importance of these. I believe that 'isms' are now over; instead in the shift from the twentieth to the twenty-first century we moved to an era of remaking, rethinking, redoing and re-evaluating.

AGThis idea of remaking or revisiting the past in order to progress is interesting and brings us to some of the core curatorial concepts that Okwui Enwezor brings up in All the World's Futures. I am interested to discuss Venice and the works to be exhibited?

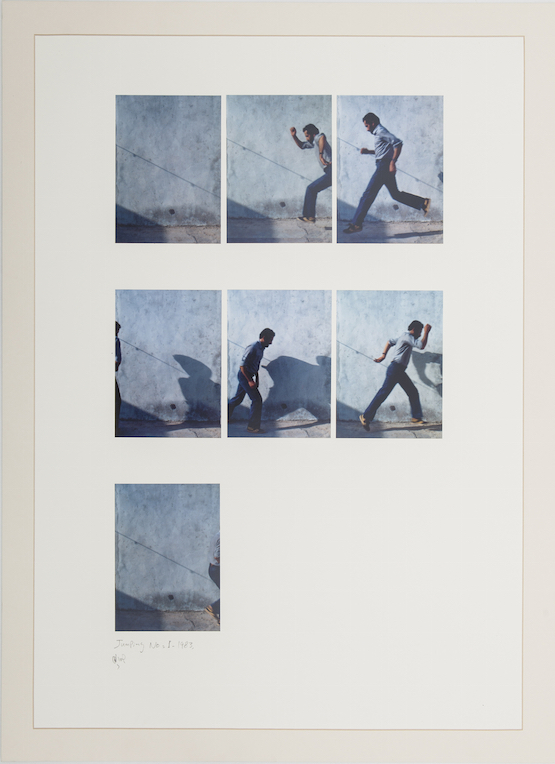

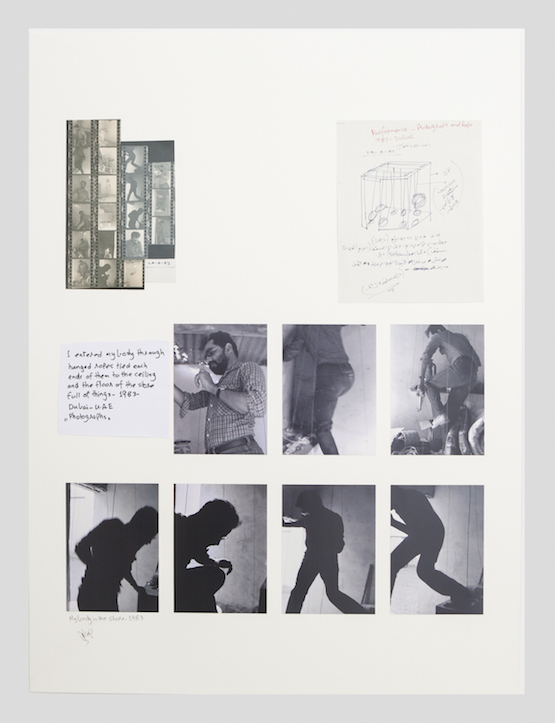

HSHoor Al Qasimi took a selection of works, mostly my older performances and experiments, focusing on 1983, including: My body in the store, Sound of the act, Recording Stones and the Jumping series.

I was still living in the UK then, but I used to come back in the summer holidays, because I was working in the ministry so when there was no study I would have to come back. Effectively I was employed. I was already doing performances in London, which had been photographed. But in London, these were really public performances, in public spaces, but here I went to the desert, it was private.

The aura no longer exists in the artwork, but instead in conversation.

AGThere is a quote I wanted to share with you that ties into the biennale (from Walter Benjamin's Theses on the Philosophy of History):

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.

The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

When I looked at your recent sculptural pieces, they could almost be a visualisation of this quote—the cascade of magazine pages, the accumulated dictionaries, they act as a stream of consciousness. Obviously the UAE Pavilion has a different theme tied into it, but Hoor Al Qasimi has looked towards pinpointing a particular time within the history of contemporary art in the UAE.

HSYes, Walter Benjamin is important. In 1936 he wrote an article called The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (or Reproducibility).

It was his concept surrounding the 'aura' of the image, painting or artwork that is of interest to me—this idea that this 'aura' has effectively disappeared—and he is right. We no longer have this same attachment to the idea of a Picasso or a Van Gogh painting, we are not capturing time and place anymore through the work, this enchantment by the idea of the touch of the artist has gone. The aura no longer exists in the artwork, but instead in conversation. This is why audio is important. Sound has more impact than a painting now.

I went to see Laurie Anderson perform in the eighties in London. At the time she was just making sounds, going back to pre-language. Before language, we had sound, before we even had hieroglyphic drawings. There are many things in the deep and profound past that I believe we could be revisiting now. And this is what my work has become about.

If you look at my works, they are handcrafted, but with a complete lack of skill utilised, they are raw actions. I prefer now to use found material that has its own history attached to it, I used to buy materials from markets for example, but now I am moving towards only reused materials. Giving them a new purpose or new home, allowing their unknown history to exist as opposed to starting from scratch.

Ezra Pound was the originator of the 'Make it New' slogan at the beginning of the twentieth century, and this phrase is useful for all ages and all times and it's very important.

AGYes, reimagining possibilities too is important. If we turn this towards the social role of artists, here in the UAE, do you think there are some new approaches artists could be employing that lead to social engagement and activism?

You have played an instrumental role in art in the UAE and wider region. You left the country just after a time of change across the Middle East, when there was a shift away from Westernisation and towards reimagining something alternate and derivative of this region instead. You also aligned yourself to constructivism, to art as a practice with a social purpose.

When you ask people, perhaps artists more specifically, to reimagine or to 'make new', do you consider that this is pertinent in a nation that is characterised, or perhaps stereotyped, by its transiency, by a very fluid society that is made up largely of expats and one of such rapid urban change?

HSI think that this is where education is important. Education in order to respond to the changing audience. Artists here have to constantly re-discover their audiences. At the same time, everything is nascent, so they also are still one of the first generations to be responding to society, to pertinent subjects, through art.

I am saying that artists should not be afraid of the new.

There is also a risk that artists from the UAE, or the region, fear a loss of identity. This is fuelled by the consumerism we discussed earlier. But, it is impossible to lose ones identity, in fact, that is a ridiculous statement—'finding oneself'.

Similarly, it is impossible to find identity through consumerism or through objects and belongings. The artists should find a freedom in their practice that doesn't exist elsewhere and not try to conform to a particular style or category. For example, notions of 'Arab' painting, 'Arab' nationalism etc. are flawed.

AGDo you think there is an underlying role or responsibility for artists here to accelerate or tackle these questions of capitalism? To find approaches that take people's minds towards something different, towards an alternative?

HSI am saying that artists should not be afraid of the new. They should not be afraid to move away from heritage, away from notions of identity and national identity and away from nostalgia.

There is a certain fetishism attached to heritage here in the region, a yearning for the old, for a time which to be honest was not particularly pleasant. Memory is playing tricks on people. We had very little water, no air conditioning, poor housing, barely any electricity—and that was just recently, in the seventies ... this has all changed radically.

This yearning is unhealthy for a number of reasons and doesn't allow for the discourse and support that the community so needs. Mohammed Kazem, Layla Juma, Abdullah Al Saadi, Ebtisam Abdul Aziz, they all work outside of these boundaries and are important to consider for that reason. Being in the moment, in the now, existing only in the current is important.

AGThat's a beautiful statement for any artist to hold on to. Because inevitably, you cannot avoid history. It will come up on its own. You don't need to focus on it.

HSYes, exactly. I never look back, when a problem comes up behind me, I jump my whole self to face it. I don't turn my head and look backwards. My whole body moves so that I am always facing the future, whatever it may hold. As I mentioned before, the future is forcing itself on us, there is nothing to do but to face it. —[O]