Diriyah Biennale ‘After Rain’ Draws Inspiration from Renewal

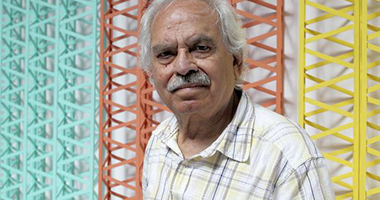

El Anatsui, Logoligi Logarithm (2019) (detail). Exhibition view: Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024: After Rain (20 February–24 May 2024). Courtesy the Diriyah Biennale Foundation. Photo: Alessandro Brasile.

With its petroleum bounty under the sands and holy mosques above, Saudi Arabia has long been run on strict Islamic lines, with its rulers carefully calibrating foreign influence. Recent reforms are transforming the country, with restrictions eased for women driving, public cinemas, music festivals, and tourism; even the sale of alcohol is on the cards.

More broadly, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's Saudi Vision 2030 charts an ambitious course to a post-petroleum future for the country through investments to the tune of U.S. $500 billion. One of many such ventures is The Line in Neom, a linear city designed to be traffic and emission-free. For the historic capital of Diriyah, the projects include heritage revitalisation and the arts—and, somewhat improbably, a Saudi version of the Champs-Élysées.

Despite—or perhaps because of—such overarching logics of soft power, the second edition of the Diriyah Biennale, After Rain (20 February–24 May 2024), hews to a familiar biennial format. A range of artworks—spectacular, thoughtful, or otherwise—dot six warehouse spaces and outer courtyards, while an artist-run communal kitchen and juice bar showcases social forms of artistic practice.

On the whole, being well-funded, the Biennale is well-installed, without seeking to reinvent the wheel. Given the event is set in relief against some of the country's more ambitious projects, I could not help but wonder: what if the biennial included wilder propositions, or played with exhibition-making practices beyond an international art-world norm?

Nevertheless, After Rain draws inspiration from a tremendous sense of renewal in the country—and the intensely earthy smell, known scientifically as petrichor, that emanates when rain lands on dry soil. This scent guides the curatorial approach of Ute Meta Bauer and her team, linking science and the senses, surfaces and structures.

One can only hope that, like a brief but intense spate of desert rain, the Diriyah Biennale will nurture an oasis of regenerative potential.

Themes revolve around waterways and toxicity, natural and human environments, and extend to performativity, modern art histories, time, and space. Lurking in the backdrop, however, are questions about how artists negotiate resistance and compliance.

One work best exemplifies this tension. Charivari (2019), an installation by the Dagestani artist Taus Makhacheva, greets visitors with abstract circus forms—ladders, hoops, and towers. Whispered recordings, drawn from archival circus materials, tell of fictions and half-truths.

'Charivari' refers to a traditional circus performance in which solo and group acts are staged all at once. As the show goes on, the rhythm revs up and movements multiply, merging into a kaleidoscopic ensemble. For the artist, the circus offered 'a space of freedom within a society controlled by ideology and state narratives', providing glimpses of alternative possibilities beyond the here and now.

Might this be a poignant metaphor for the contemporary biennial—particularly this one, situated in a state that brooks no dissent? As jesters of sorts, artists play fast and loose with control; at the same time, they can become caught up in the spectacle, whether of the market or the state. As a whispered line in Makhacheva's work goes, 'Good treatment and a strong whip—that's the key to a successful performance.'

One significant strand of works in the Biennale explores the impact of scientific rationality and extractive capitalism on natural and human environments. Other works also engage critically with ethnographic or native-informant positions—with varying degrees of success. In the Black Box, a screening room hosting most of the moving-image works, Sammy Baloji's Aequare, the Future that Never Was (2023) examines the lingering legacy of overcultivation in Belgian Congo through haunting landscape shots of absence.

Liu Chuang's Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018), meanwhile, delves lyrically and speculatively into the linkages between infrastructural statecraft, cryptocurrency mining, and Indigenous habitats in upland Southwest China. Through a spellbinding array of moving images—drone footage of bitcoin mines and archival clips of infrastructure, among others, ending with a montage of a woman in Mongolian wedding dress morphing into Padmé Amidala from Star Wars—the work blurs fact and fiction while musing on the dialectic between state order and recurring escapes from control.

A personal highlight of the Biennale is Alia Farid's video Chibayish (2023), in the section about water and toxicity. The artist captures young residents in the southern marshes of Iraq telling the story of a water buffalo, through which they gradually reveal their way of life and an ecosystem under threat of war and extractive oil infrastructure. Drained and then re-flooded in the 1990s, the Iraqi marshes subsist and survive, and the work weaves an intimate yet magical tale of memory and loss from the accounts of the marsh dwellers.

Works with a conceptual gap between form and meaning leave room for play. One example here is Dala Nasser's installation Mineral Lick (2019), in which the artist created a 'hydromap' of Beirut by soaking fabrics in a mixture of dye, rock salt, and tap water from all 60 sectors of the city. The varying acidity levels in the water led different salts to grow on the textiles: much as photographs capture light, this long train of weathered fabric indexically records Lebanon's toxic mismanagement. The shimmering colours, a metaphor for the country's beauty, stand in stark contrast.

Another example is the striking installation Tuban (2019) by Ade Darmawan, a member of the Indonesian collective ruangrupa. Inspired by Pramoedya Ananta Toer's novel Arus Balik (1995), which recounts the world of the Indonesian archipelago on the eve of colonisation in the 15th century, the artist sought out the natural resources mentioned in the historic epic.

Assembling beakers, heaters, and tubes, Darmawan set up a laboratory distilling spices and leaves—including nutmeg, sandalwood, cinnamon, and clover—into fluids that drip onto and spoil the open pages of nationalistic tomes produced in Indonesia during Suharto's regime. While critiquing the extractivist greed that powered colonial empires as well as post-colonial nation-states, the work also gestures at vertiginously unfamiliar perspectives—alchemical, artistic—that extend beyond rationalist means of yielding truth.

While numerous works offer critiques of contemporary conditions in other countries, those directly addressing contemporary Saudi contexts appear distinctly more muted or oblique in bite, with the curators—unfortunately, albeit understandably—leaving viewers to draw their own interpretive conclusions. Artists and curators alike walk a tightrope between political sensitivities and creative resistance: the paradox of censorship (and taboo), of course, being that everyone has to know exactly what not to say in order to avoid saying it.

As jesters of sorts, artists play fast and loose with control; at the same time, they can become caught up in the spectacle, whether of the market or the state.

The photographic installation Saudi Futurism (2024) by Armin Linke and Ahmed Mater, for instance, examines the implications of the country's startling evolution through shots of industrial, scientific, and historical sites. The images are left to speak for themselves, however, devoid of any curatorial commentary. Unlike Mater's earlier photographic essay, Desert of Pharan (2016), which documented the rapid development of Makkah, the holiest city of Islam—and managed through force of repetition and skilful juxtaposition of imagery to open up space for different perspectives and critiques of 'progress'—Saudi Futurism might easily be read as a paean to the state, whatever the artists' true intentions.

Under restrictions on overt political expression, works must try different tacks, nudging subtly at old certitudes, sometimes finding refuge in formal means. In Sara Abdu's Now That I've Lost You in My Dreams, Where Do We Meet? (2023), for instance, towers of handcrafted soaps refer to cleansing rituals that prepare corpses for burial. The work grapples with loss, absence, and memory—perhaps even our relationship to history.

The section centring the modernist art history of the Gulf and Western Asia shows how artists have historically found the space to explore, with works by prominent artists like Rasheed Araeen, Siah Armajani, Lala Rukh, and Ibrahim El-Salahi, among others. I was touched by a series of Chinese ink drawings by Abdulrahman Al-Soliman, a respected Saudi modernist painter, critic, scholar, and educator. Palm, Bow, and Fragments (1990–1991) comprises abstract, calligraphic forms that capture the skies above Kuwait during the first Gulf War: distant missiles leave trails of sparks in the blazing sky, while the palm tree serves as a symbol of strength and perseverance.

Other standout works in this part of the Biennale include early pieces by U.A.E artist Hassan Sharif, who was inspired by Fluxus, Minimal Art, and British Constructionism. Documentary images of the performance Body and Squares (1983) show Sharif stretched out in various combinations across a grid on the floor. Toying with the interplay of chance and order—with rules set to dictate the outcome—the work manifests the power of art to birth new ways of perceiving and becoming.

And so even in the desert, life thrives. One can only hope that, like a brief but intense spate of desert rain, the Diriyah Biennale will nurture an oasis of regenerative potential. —[O]

![Left to right: Simryn Gill, Dalam (2001); Tiffany Chung, Energy Policy vol.166: potential CO2 emissions until 2050 by key fossil fuel and coal extraction projects [each>1 Gt] worldwide (2023); Christine Fenzl, Women of Riyadh (2023). Exhibition view: Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024:](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/Content/Features/2024/Diriyah%20Biennale/06-DCAB2024-Installation-Photo-by-Marco-Cappellletti-Courtesy-of-the-Diriyah-Biennale-Foundation16001066_400_0.jpg)