documenta fifteen is a sum of its parts, not a single event

Atis Rezistans, Ghetto Biennale, Ghetto Gucci (2022). Performance view: St. Kunigundis, documenta fifteen, Kassel (17 June 2022). Photo: Frank Sperling.

It was a perfect day, before things took a turn. documenta fifteen had just opened to the public, celebratory events were taking place across Kassel, and, as culture writer Siddhartha Mitter observed, everything and everyone seemed to be vibing.

'How can you capture a feeling?' asked one curator from the Philippines; others from Hong Kong and Nepal agreed. You had to be there.

But you didn't have to go to a B.D.S.M. party organised by Party Office b2b Fadescha, or catch a Black Quantum Futurism performance on the group's floating stage on the Fulda River, to feel part of it, either.

That is, lumbung, the Indonesian term for a community rice barn that artistic directors ruangrupa used to describe the process that shaped this edition of Germany's quinquennial exhibition (18 June–25 September 2022), in which a common resource (the show's eye-watering budget) was distributed among a community. (Here, a constellation of invited collectives and individuals, who in turn invited other collectives and individuals, resulting in over 1,500 participants.)

All you had to do was see some of the show, which, despite preconceptions, has great art. Like Elisa Strinna's pink porcelain Valerian root sculpture, My Body is a Plant – roots my nervous system (2022), and Nino Bulling's hanging ink-on-silk paintings of moments between lovers, Sometimes when we kiss, it feels like I am drinking water from your mouth (2022).

You could admire the show's stunning visual identity, conceived by Jakarta student collective Studio 4oo2, with colourful hands plastered across the facade of ruruHaus, documenta fifteen's 'living room' housed in a department store on Obere Königsstrasse.

Or you could get a cheese and sauerkraut sandwich outside the Museum of Natural History Ottoneum, courtesy of INLAND, a collective focused on rural collaboration.

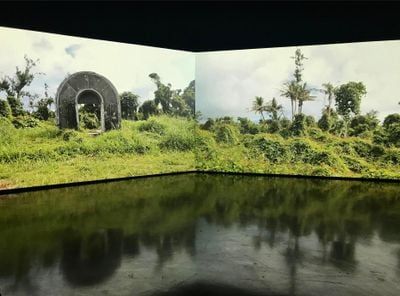

Inside the venue, INLAND introduce their alternative currency, 'Cheesecoin', sharing space with Tropical Story (2022) by Korean collective ikkibawiKrrr. The two-screen video treats footage from former Japanese-occupied sites across Asia, such as Peleliu island in the Palau archipelago, like poetic notes in a percussionist score.

Lumbung, as ruangrupa state, is not the theme of this untitled show; it's the working model that made it happen. Some have likened the endeavour to a Web3 D.A.O. (decentralised autonomous organisation), but it feels more like a grounded networking of grassroots communities, collectives, and artists, from Richard Bell, whose Aboriginal Tent Embassy stands outside the Fridericianum, to Budapest's OFF-Biennale and Haiti's Atis Rezistans.

In short: people have been invited from across the world—not just the 'Global South', which ruangrupa's Ade Darmawan calls 'a false' and reductive 'juxtaposition'—to share their work with each other and their audiences. This is not documenta fifteen's claim so much as its action.

Connections between here and there abound. Inside the dark interior of the Rondell tower, chilli plants arranged by Nguyen Trinh Thi are serenaded by the sounds of the sáo ôi flute. Their leaves cast dancing shadows on the walls, triggered by fans and lights connected to a wind and WiFi system in Vietnam.

At documenta Halle, Britto Arts Trust's hall-spanning mural weaving scenes from Bengali movies (Chayachhobi, 2022), faces Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture's The Rituals of Things (2022). The four-screen video installation tracks exchanges between dairy farmers in Kassel and the town of Nongpho in Thailand, alongside shadow puppets for Ramayana epics and Brothers Grimm fairy tales, and a skate ramp flanked by electric light mills.

In some cases, ruangrupa invited organisations to regroup; like Sada, founded by Rijin Sahakian, which supported artists in Baghdad between 2011 and 2015.

A cycle of videos at the Fridericianum include Sajjad Abbas' I CAN SEE YOU (2013), also showing at the Berlin Biennale, which documents Abbas painting the work's title on a building facing Baghdad's fortified Green Zone, where he unfurled a black-and-white banner of his eye. The intervention was quickly taken down, only to be raised again in 2019, amid an uprising in a country still reeling from the 2003 American-led invasion.

The lumbung curatorial logic is palpable at a site like Hübner areal, an industrial complex where presentations by artists, collectives, and organisations unfold across 7,500 square metres.

Among them is Guangzhou collective BOLOHO's working Cantonese canteen, complete with painted screens and T.V.s playing gleeful dramatisations of the collective's collaboration like a sitcom; and Cambodia's Sa Sa Art Projects, whose group-show-within-the-supra-group-show includes Ngoc Nau's Ritual Objects 1 (2019), where circular mirrors embedded in a hanging fabric screen turn real and virtual footage of rituals into light orbs on the wall.

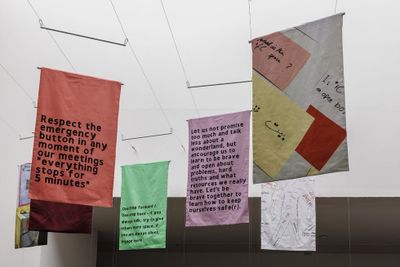

Imaginative and context-specific formulations around the action—not just concept—of communality are at the heart of documenta fifteen, and extend to other projects at Hübner areal.

Lumbung, as ruangrupa state, is not the theme of this untitled show; it's the working model that made it happen.

Taking up a section of the ground floor is Fondation Festival sur le Niger, founded in 2009 to support the Festival sur le Niger, which became one of the largest cultural events in West Africa after it started in 2005 in Ségou, Mali.

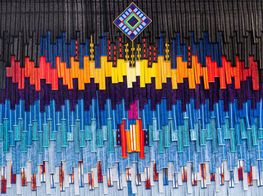

Works include Abdoulaye Konaté's Hommage aux chasseurs du Mandé (1996), a large earthen fabric panel hosting figures created with talismans and cowrie shells that won the 1996 grand prize at Dak'Art; and sculptural hangings of folded cardboard blocks wrapped in thread by Losso Marie-Ange Dakouo, whose brilliantly lit monumental spiral ADN Collectif (2021) casts a spectacular shadow.

The title of the Fondation's presentation, Le Maaya Bulon / Vestibule Maaya, refers to the room in a Malian house where hospitality is practised, but also echoes the festival's origins.

Founder Mamou Daffé originally owned a video store in Ségou that doubled as a meeting place. When video fell out of fashion, Daffé opened a hotel but realised people didn't stay in Ségou much, so he rallied the community to imagine, establish, and support a festival rooted in the concept of 'Maaya entrepreneurship'.

At the heart of Maaya entrepreneurship is knowing your community and yourself—an ethos that comes through beyond collective participations in Kassel. A case in point is artist Amol K Patil's stunning presentation Black Masks on Roller Skates (2022), which unfolds across a massive chunk of Hübner areal's basement.

A series of bronze sculptures and paintings depict body parts, sometimes disembodied at other times multiplied, as with a clay-like slab of cast bronze from which ten profiles line up vertically.

In one corner of the space, which is filled with irregular wooden soil boxes, a video shows Patil rollerskating in Mumbai. He holds a radio playing a song about people who 'dug the land with the toil of [their] hands'—an homage to Anil Tuebhekar, a Dalit who swept the street on roller skates with a radio at his waist.

'He cleaned the city, but knew he wasn't welcome into the bus or in the hotel for a drink of water,' Patil states. 'Shutting the world out with music was his individual protest.'

Songs are sung throughout documenta fifteen. From those heard through speakers in MADEYOULOOK's installation Mafolofolo (2022) at Hotel Hessenland, whose ballroom has been transformed into a three-dimensional topographical map, to those performed in works by Rojava Film Commune at the Fridericianum, including Shero Hinde's joyful music video for composer Mehmûd Berazî's Kurdish acapella ensemble, 'Nazê Nêrgiza Hewşê' (2020).

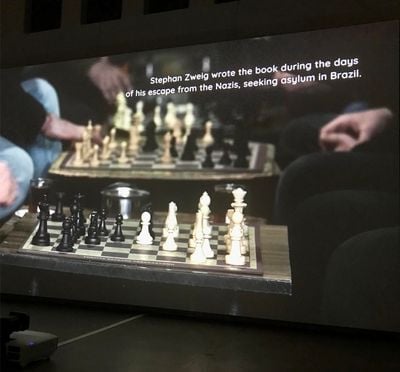

Darên Bi Tenê (Lonely Trees) (2017), also directed by Hinde, invokes the words of Kurdish politician Abdullah Öcalan, whose egalitarian form of governance, democratic confederalism, has been enacted in Rojava: 'Our lives cannot be explained with books, only with songs.'

The film, presented on a monumental screen, tracks the musical traditions intersecting across the so-called Fertile Crescent while highlighting the landscape's role in shaping them, from the popular songs of Arab and Kurdish Bedouins, to Assyrian raweh.

'The art and culture of people who live on this land is similar,' says one man in the film, because 'nature is the source of this art.' It's a vital observation recalling one of Dan Perjovschi's drawings on the plaza in front of Kassel Hauptbahnhof, where 'NATURE' is written under an image of the earth, and 'CULTURE' under a shipping container.

At documenta fifteen, art is nature. It is alive, evolving, and certainly not something to be contained by the formal tastes of high-end international art fairs and their patrons. (A fact that adds another dimension to Marwa Arsanios' beautiful contribution, Who is Afraid of Ideology? Part 4, a 2021 video that starts by asking viewers to imagine a land untethered by the private property regime—the same to which the art market is tied.)

Take Water System Refuge (2019–2021) by Chengdu-based artists Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun, shown at Hafenstrasse 76. The video records testimonies of ethnic Qiang grappling with the loss of their culture due to the disappearance of traditional agriculture after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.

But rather than settle on that conclusion, young people describe how their community is adapting—a view that invokes the Indigenous futurism illuminated by Moana Oceanic collective FAFSWAG, who express Indigeneity as a charged, lived reality.

FAFSWAG videos are screened on a loop at Stadtmuseum Kassel, where high vogue and trans-living intersect with a constellation of cultural and aesthetic vernaculars.

Among them is Pati Solomona Tyrell's Pasifika spiritual Fāgogo (2016); Tanu Gago's choreography of the queer masculine Indigenous experience in Aotearoa, Apparatus (2018), with its masterful use of tracks like 'Garden' by Emeli Sandé featuring Jay Electronica & Áine Zion and FVBIO's 'Chrome'; and Gago's poetic dance portrait of diasporic womxn, Diaspora (2021).

In the same venue, Safdar Ahmed's Border Farce-Sovereign Murders-Alien Citizen (2022) centres on a two-channel video installation created with Alia Ardon.

Blending documentary and performance, death metal is introduced as a form of healing and community. Scenes include musician Kazem Kazemi recounting his six years at Australia's Manus detention camp, performing with Ahmed as part of their band Hazeen, and eating at the kitchen table in full corpse paint.

FAFSWAG reappear at Hessisches Landesmuseum, with an A.R. work visualising the celestial Te Kore, 'a mighty chaos'. They share the venue with Pınar Öğrenci's Aşît (2022), a colossal film charting the lived histories of a mountainous region on the Turkish-Iranian border through Öğrenci's return to her father's hometown Müküs, where Armenians, Kurds, Persians, and Arabs lived together before the Armenian genocide.

A short walk away at GRIMMWELT, dedicated to the Brothers Grimm, are a series of context-appropriate interventions. Nestled among the museum's exhibits is Jumana Emil Abboud's The Unbearable Halfness of Being (2021), a collaborative project bringing together annotated beeswax sculptures and drawings inspired by Palestinian folk tales like The Orphans' Cow, whose plot resonates with the Brothers Grimm's Brother and Sister (1812).

Installed in a space of its own, is a two-screen animation by Versia Harris as part of the Alice Yard project Telling After All ... (2022). A figure with a swan head cycles through a greyscale landscape that flashes with technicolour details from Disney movies, like Sleeping Beauty's dress and true love kisses.

Alice Yard, a collective headquartered in Port of Spain, are also at WH22, with works by nine Caribbean artists like Blue Curry, whose Leisure Aesthetics (2022) install includes a sharp floor assemblage of materials arranged in neat squares, from conch shells lit from within by flashing L.E.D. lights to white synthetic braids with gold beaded edges.

Artist Hamja Ahsan is also present, with a sign for 'Kabul Fried Chicken–Graveyard of Empires'. It's among a series of halal fried chicken signs installed across documenta's venues that interrogate histories of occupation, displacement, faith, and resistance. (At the Museum für Sepulkralkultur, one for 'Final Fried Chicken' appears amid artefacts focused on death.)

Also at WH22 is an exhibition organised by The Question of Funding, with works by the Gaza-based Eltiqa collective, from luminous cacti paintings by Mohamed Abusal to digital collages from Mohammed Al Hawajri's 'Guernica Gaza' series (2010–2013). The latter superimposes images from the Israeli occupation onto modern paintings like Millet's Harvesters Resting (1850–1853), recalling Martha Rosler's agitprop collages 'House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home' (c. 1967–1972).

Graffiti in this location brings this text closer to events that erupted after the preview. In May, vandals sprayed '187' and 'PERALTA' inside the building. (In The Question of Funding gallery, 187 appears crossed out, and a P stands alone.) The number is believed to reference the California Penal Code section for murder; the name seemingly refers to a far-right personality reportedly barred from entering Germany in March, after Nazi material was found in their luggage.

By that time, documenta fifteen had become embroiled in an intensifying furore, with participating artists and selection committee members called out in the press as antisemitic (and attacked and threatened as a result) for their support of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement (BDS).

The movement, condemned by Germany's parliament as antisemitic in 2019, aims 'to end international support for Israel's oppression of Palestinians and pressure Israel to comply with international law'.

Imagine the devastation, then, when Taring Padi—whose powerful exhibition of paintings at Hallenbad Ost tracks the collective's community activism in Indonesia—unveiled People's Justice (2002) on the Friedrichsplatz, just after the preview.

The now-notorious mural of a dense crowd contains two antisemitic depictions amid a line-up of agents that refer to the geopolitical forces believed to have supported General Suharto's anti-communist regime in Indonesia, which encouraged the mass killings of between 500,000 to one million leftists in the 1960s.

It was a demoralising and damaging oversight; something that gave naysayers everything they needed to dismiss a show that is so much more than this one glaring mistake. (The kind you would have hoped that, in its intimate entanglement with the German context and support of ruangrupa, documenta's management would have kept an eye on.)

What has since ensued is a tumultuous confrontation—both revealing and potent in its lessons—between documenta and its publics. Whether in terms of recognising antisemitism regardless of context, acknowledging the histories of colonialism and nationalism and their racist affects, or challenging the conflation of antisemitism with critiques against the Israeli state's treatment of Palestinians, particularly in the occupied territories.

The latter seems to be reaching boiling point in Germany, where, on 17 June, the Goethe-Institut disinvited activist Mohammed El-Kurd from a conference in Hamburg. El-Kurd, who addressed the UN General Assembly in 2021, has been documenting forced evictions of Palestinians from Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem; including the occupation of his family house by settlers. (One of whom was filmed saying if they didn't steal their home someone else would.)

At a symposium organised by the 12th Berlin Biennale, Forensic Architecture's Eyal Weizman—describing himself as an Israeli Jew who supports BDS, and whose collective, which has been called antisemitic in the German press, has worked with El-Kurd—weighed in on People's Justice and El-Kurd's disinvitation.

Context-specific formulations around the action—not just concept—of communality are at the heart of documenta fifteen.

Talking frankly, Weizman observed a political tendency in Germany to 'insist that antisemitism is an imported problem,' as if 'German racism ... had been dealt with.'

His point speaks to a paper by Hito Steyerl criticising documenta's unwillingness to face its own context (not limited to its co-founding by a Nazi), written for a cancelled documenta-run forum on antisemitism and anti-Palestinian racism, no less. It also speaks to reports of abuse experienced by documenta artists in Kassel, most recently leading Party Office to suspend planned events.

Many documenta fifteen participants—including Steyerl, who's pulled out of the show—feel these issues have not been adequately addressed by the institution or the German press, who have been driving the national discussion around the exhibition.

Even the Anne Frank Educational Centre—whose director just quit as advisor to documenta, publicly accusing the institution of treating ruangrupa with a neocolonial attitude and preventing the collective from participating in a panel on the issue of antisemitism in June—released a statement in July. It calls for a constructive, nuanced discussion that neither labels the entire 1,500-artist show as antisemitic nor the debate on antisemitism in Germany as 'provincial'.

ruangrupa, meanwhile, have apologised and answered to the Bundestag, outlining the contextual precedents—among them, the stoking of anti-Chinese racism in Indonesia by Dutch colonisers wielding antisemitic tropes—through which history, as Darmawan testified, has come full circle in an incident that the collective, and others, must now process and learn from.

All of which loops back to Weizman's Berlin talk, where Weizman likewise described the boomerang effect of racism's export and return. The denial to critically and honestly address issues of antisemitism and racism, Weizman argued, not only creates a vulnerability for Jews and Palestinians 'facing ongoing racist attacks' in Germany. It damages 'potential solidarity and common struggle between Palestinians and Jews that feel and work for Palestinian liberation'—what Weizman described as a 'fragile, very complex relationship that we are trying to build, slowly.'

That task of building intersectional solidarities across insurmountable divides and dominating narratives is what ruangrupa likewise attempted through documenta fifteen. 'A way', to borrow Amol K Patil's description of his installation, 'to think the now, combining what's harsh and polite, sweet and silent, pitching a criticism of land politics and social separation'.

While things faltered pretty spectacularly, with an incident that caused real hurt, it doesn't seem fair to completely dismiss the lumbung's efforts to foreground practices—so many of them defined by joy, humour, grace, and pathos—working on the ground, across the world, for more inclusive futures, and often against unbearable odds.

Walking through the Karlsaue Park with one curator on that perfect day before things blew up, memories arose of Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev's documenta 13, which packed this green site with Artworks with a capital 'A'.

With only a few interventions to count—among them, Más Arte Más Acción's architectural installations that include a circular bench framing an old tree, and The Nest Collective's critique of the global clothing industry, Return to Sender (2022)—we commented on how generous this edition felt. Despite the dense sprawl—and with a central show that, unlike editions 13 and 14, is solely grounded in Kassel—there was space to take everything in, without losing the momentum that charges all practices involved.

That's the thing about this documenta, which avoids the current Berlin Biennale's static didactism and the mainstream finesse of the Venice Biennale's central show, and opens up horizons in the process.

In its undoubtedly well-intentioned effort to use a compromised exhibition platform and its resources to connect people and places within and beyond its remit, this ambitious project recalls one description of Maaya entrepreneurship: as something that evolves 'by trial and error.'

Humility and courage, not to mention transparency and care, define this kind of experimental, collective, and ultimately messy work. These are vital qualities to have in any attempt at testing the boundaries of what's possible, because mistakes happen when alternative pathways are sought out in common, and room for mutual learning and understanding is needed to reckon with them.

With two months left—and events still happening—perhaps documenta, the lumbung community, and its audiences can create that space for a show that remains unforgettable for so many reasons. That said, with the networks created through documenta fifteen extending beyond Kassel, which feels like a hostile environment for some, perhaps that space will (or should) manifest elsewhere. —[O]