Ali Cherri: 'My work is about finding solidarity'

Ali Cherri. © The National Gallery.

Ali Cherri. © The National Gallery.

Dreamless Night, Ali Cherri's latest exhibition that launched at GAMeC, Bergamo, before it opens at Frac Bretagne, Rennes, in February, is a timely meditation on the terminal inertia that war can induce on body and land.

Curated by Alessandro Rabottini and Leonardo Bigazzi of Fondazione In Between Art Film, Dreamless Night (10 February–19 May 2024) centres on The Watchman (2023). The short film follows a Turkish-Cypriot soldier as he mans a watchtower on the dividing line between the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and the Republic of Cyprus.

The soldier guards what increasingly feels like an atemporal space, where the spectre of war lingers on the horizon. That constant tension defines Cyprus, an island in the East Mediterranean on which an enduring and unresolved fault line was inscribed during the Cold War.

It was in 1974, amid a coup against Cyprus' democratically elected president orchestrated by the U.S.-supported dictatorship in Greece, that Turkey invaded the island. Existing tensions between Greece and Turkey over rights to the Aegean Sea, exacerbated by the discovery of oil and gas in its waters and OAPEC's decision to impose an oil embargo on the U.S. in response to the Arab-Israeli War in 1973, were thus intensified.

Then, as Cherri points out in this discussion, the Lebanese Civil War erupted in 1975. Cherri finds geopolitical resonances between the Cypriot capital of Nicosia, known as the world's last divided capital city, and Beirut, which was divided during the Lebanese Civil War. But The Watchman does not unpack these histories. Rather, their shadows infuse an allegory of war embodied by the film's protagonist.

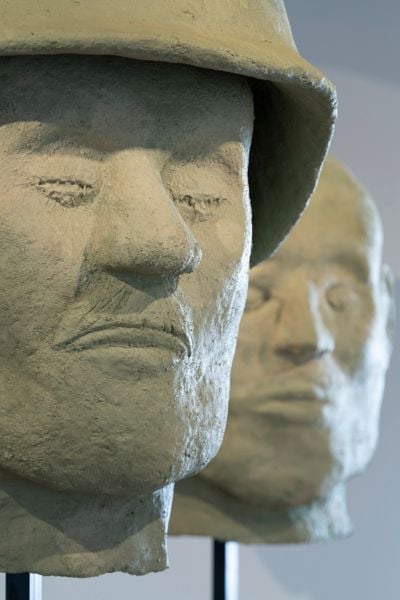

As the sun goes down, he enters a dream-like world. A ghostly battalion emerges like an abstraction of a modern army, embodied by Cherri's sculptures created for Dreamless Night. The Seven Soldiers (2023) comprises seven giant resin heads of soldiers supported by a stake-like stand, while Wake Up Soldiers, Open Your Eyes (2023), comprises two standing soldiers cast from mud and plaster.

The Dismembered Bird (2023), a massive, antique Prussian eagle's head with a body composed of fragments cast out of mud, sand, and resin, connects to the mud bodies with ancient artefacts for heads that Cherri presented at the 2022 Venice Biennale. They were shown alongside Of Men and Gods and Mud (2022), a three-channel film weaving footage of brickmakers in Northern Sudan, as a narrator describes myths of the first humans fashioned from mud.

There's a relationship between Of Men and Gods and Mud and The Dam (2022), Cherri's feature-length film zooming in on one brickmaker who builds a mud structure in the desert amid the Sudanese revolution. 'One needs the other and they support one another, but they are also really separate self-standing projects,' Cherri explains.

The Dam, which premiered at Cannes in 2022, is part of Cherri's 'Geographies of Violence' series alongside The Disquiet (2013), exploring the geological faultiness beneath Lebanon, and The Digger (2015), where a Pakistani caretaker of a Neolithic necropolis in the Sharjah desert goes about his rounds.

In Dreamless Night, one remarkable sculpture manifests another kind of violent geography. The Prickly Pear Garden (2023) grafts cladodes cast from the ubiquitous Mediterranean prickly pear cactus, creating jaundiced-green resin and fibreglass cacti tinted with infusions of sand that line up like a barbed fence.

Precise and intimate studies like these, of the ruptures that shape the land's formations and inhabitants, define Cherri's practice, where bodies align through violence—something the artist elaborates on in this discussion.

SBThe Watchman follows a soldier in Cyprus who encounters—or imagines—a ghostly army while standing guard at his post. What emerges is a reflection on war and what it demands of its soldiers. Could you talk about that?

ACThe guard is a figure I keep going back to. It's there in The Dam and Somniculus (2017), which means light sleep, where I am filmed as a sleeping guard in different museums, like the Louvre. In The Digger, too, there's someone guarding the ruins.

I think there's something interesting in the figure of the guard who keeps watch when nothing's happening, when waiting is not just a temporal experience but also a spatial one. That's what the soldier embodies in The Watchman: he is in this space of waiting for the enemy, and when the enemy doesn't come, he has to invent one to give meaning to this waiting.

Coming back to your question, this is a reflection on the ideological construction of the military and what it asks of our bodies. The line that appears in the film, 'Wake up soldier, open your eyes', for example, is a song from the Turkish army. The army wants its soldiers to be alert and awake and ready, so I respond with a soldier who imagines other realities to resist falling into sleep. I see this as a political fable. A little story anchored in a political reality.

The relation between how I create sculptures and films is quite similar: you always start from existing stories.

In terms of the sculptures, The Seven Soldiers references Akira Kurosawa's film Seven Samurai (1954). It's not an obvious reference. Kurosawa also has this short film about dead soldiers who return to their sergeant to blame him for their death. Wake Up Soldier is based on photographs of sleeping soldiers. Standing, they embody this state between falling and sleeping, and there's a vulnerability to that.

SBSince you made The Disquiet in 2013 in Lebanon, you have created films that are anchored to a specific context, from the U.A.E. in The Digger to Sudan in The Dam, and now Cyprus in The Watchman. How do you see The Watchman in terms of how your practice is evolving?

ACIn my mind, The Watchman was always going to be a precursor to my next film, which I am starting to develop now, that is set in Lebanon and also centres on a guard. I've had a kind of blockage with Lebanon and have been unable to film there since 2013, when I made The Disquiet, because of everything that's been happening, of course most recently with the catastrophic port explosion in 2020.

Since The Disquiet, I have filmed The Digger in the U.A.E., The Dam in Sudan, and now The Watchman in Cyprus, and if I look back, I've been circling Lebanon without addressing it directly. When you think about the politics of borders, all these films are geared towards thinking about the post-war Lebanese experience.

These films are all part of a series I call 'Geographies of Violence'—the starting point is always a land in conflict. We begin from a place where violence has happened and from there, I try to build a fictional story rather than a documentary.

I'm always thinking about how you can turn the trauma of a violent event into fiction in my films, but the story always begins with real people and real locations. I have never worked with actors and always work with actual people. In The Dam, those are real workers you see. From there, I explore the possibility of opening up that reality; to create a fictional story out of a real place.

I took that approach with The Watchman. The Turkish village where the film is set is an almost abandoned village on the dividing line between the north and south of Cyprus. It was a Turkish-Cypriot village within the context of Cyprus before the Turkish invasion in 1974, and since Turkey occupied the North this village has basically become a pocket of Northern Cyprus inside Greekland. That was the starting point for me.

SBCould you talk about the soldier and the grandmother in the film, and the context they represent?

ACWhen Cyprus became part of the European Union, all Turkish-Cypriots born in the north gained European citizenship because European law technically considers this European land under Turkish occupation. The north is occupied land for the rest of the world but for Turkey, Northern Cyprus is a self-declared republic.

So there is this status in Cyprus of being both occupied and self-declared. But for the people living there, there are calls for unity. The North voted for reunification in 2004 but the South rejected it, so it didn't happen. Then around 2011, people occupied the Buffer Zone calling for reunification of the island. All this forms the context in which The Watchman is filmed.

When you think about the politics of borders, all these films are geared towards thinking about the post-war Lebanese experience.

For the character of the soldier, the criteria was to look for someone who had just finished his military service. I wanted to find someone who was still really in their experience of being a soldier in this place. He's not from the actual village. The grandmother you see in the film is from the area, which adds to how their relationship plays out.

I can really identify with that when I think about Beirut and its own divisions. If you want to characterise it a little bit, West Beirut and East Beirut are like the North and South of Cyprus in terms of dynamics, which of course includes religion. You have all these parallels.

SBThe date of the Cyprus invasion is also not insignificant within the context of the Middle East during the Cold War. It was just after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, and amid the oil embargo.

ACExactly. And this was also around the time the Lebanese Civil War started, so there's a parallel in terms of a land becoming divided—the beginning of the separation war in Cyprus was also the beginning of the Civil War in Lebanon.

So for me, Cyprus has always been like an echo chamber for Lebanon—in fact, when the port explosion happened in Beirut in 2020, it was heard in Cyprus. It's as if whatever happens in Lebanon reverberates in Cyprus in some way.

During the Lebanese Civil War, for example, when you could not access the airport in Beirut—which was a divided city—people took boats to Cyprus to fly, and in fact lots of Lebanese moved to Cyprus. Now with the economic collapse in Lebanon, some people have put their money in Cypriot banks.

I always find myself drawn to these situations of collapse or destruction. That's what The Dam is about. Set during the uprising against President Omar al-Bashir's regime, it considers the dam as a form that connects oppressive regimes around the world, whose construction disrupts ways of life in terms of people and the environment. The Sudanese dam is considered one of the most destructive in the world. The point of destruction in terms of The Watchman is the dividing line.

So as I said, filming The Watchman in Cyprus was a good way to start testing things that I want to do in Lebanon in the next film. As it is not my country, I can deal with it with a bit more distance before embarking on this future work, where I want to shoot on the border between Lebanon and Syria.

SBCould you talk about this new film?

ACBecause I've only just started developing it, there is only so much that I can say, but the questions I have all started with The Watchman. The question of the enemy, of waiting, of what a border is, whether a border between here and there, between fiction and reality, between fear and safety—all the different meanings of what a border is.

I always come back to this question of how you inhabit the border. I come from the south of Lebanon, and I grew up when Israel was still occupying the region, when we needed to cross Israeli checkpoints to get to the village. So for me, the border was this buffer zone. Now I'm revisiting lingering questions that I now feel ready to confront.

SBHearing that you are coming back to Lebanon for the first time since you made The Disquiet, it feels like your practice is coming full circle. How has your approach to filmmaking evolved throughout this period?

ACI think I feel at ease with this idea of fiction now, having moved further into it through my work. The Disquiet still takes on the form of an artist essay, or a film essay; it has a voiceover, while The Digger is a silent film that I treated really cinematically.

The Dam was the turning point for me because I used this work to think about how to build fiction from a reality of hardship, violence, and conflict. And for the first time, I had a scenario to work from; I really went into a cinematic mode of production.

I also worked with a scenario for The Watchman, because I was working with a team and everything had to be scripted. I used to think this was a limiting way to work. Before, I would just film and write the film at the editing stage. But this time, I created a storyboard, frame by frame, and discovered that it's not limiting. It pushes your idea further because you have to be clear about your vision.

SBThe scenario you write also becomes the tool to collaborate with your crew, which decentres your authorship. This connects to how you work with real people as actors and the politics of that. How do you navigate the dynamics of entering a space as an outsider and working with people there to tell a story rooted in their context, which can teeter into extraction?

ACThat's always the question. It's very tricky. I'm going to a place that's not mine. There's the question of legitimacy. There's the question of being aware of where I'm talking from. I'm not telling people's stories, but it's still my film. I don't want to take their voices. I don't want to take away who they are. So there is a lot of negotiation and care when it comes to what I can and cannot say. I am also very careful not to position myself as a saviour.

When I think about The Dam, this film just so happened to be the first film that was made in Sudan and released after the revolution there. All of a sudden, even for the Sudanese, it became very important. It was the first film that talked about, at least in the background, the revolution. There is a weight and responsibility that comes with that. Can I be here in Sudan telling this story?

I'm going to a place that's not mine. There's the question of legitimacy. There's the question of being aware of where I'm talking from.

It's scary because the question of legitimacy is very valid. All these questions are in my head all the time. The way I try to approach it is to be as transparent as I can about what I'm doing with the people I am working with. These films are still a contract between a filmmaker and an actor, and I try to be very clear about our collaboration based on a contract that describes how we work together.

Most of the things I film usually come through conversations with the actors. In The Watchman, I would talk to Halil about what he was thinking and feeling while standing guard for ten hours at a time during his military service, and I would describe what intention and meaning I wanted from a scene. It is always very important that we communicate and agree on what we are doing here.

In that sense, I definitely feel more comfortable working with non-actors. Because actors are trained, you need to speak to them in the language of their training, but I didn't study cinema, so I'm much more at ease with non-professional actors in terms of connecting with them on a human level.

The relation between how I create sculptures and films is quite similar: you always start from existing stories. When I get an Egyptian funerary mask, for instance, you start from that. You have the story, the history, the imaginaries around this object and where it was taken from—you're not really starting from scratch. It's the same when you're working with actual people and actual places. You are starting from a person: where they are from, how their body moves, how they talk.

In the case of The Dam, I wrote the film for the main actor, Maher El Khair, because I knew what he could and could not do. He also wanted to be in the film. His dream was to become an actor. So The Dam became something of our shared dream: of him becoming an actor and me making my film. The first time he saw the film was also the first time that he watched a film in a cinema. And it was him on screen. Then he won a best actor award at the Cairo International Film Festival.

Even Halil, when I showed him the film, sent me a message. He told me that watching himself was the strangest experience in his life, but at the same time, he saw that he had made something positive out of his time as a soldier. These moments in my work, when a trauma is transformed into something positive, can only happen if I work with actual people.

SBThat human connection removes a level of artifice in a consciously fictionalising exercise that seems to seek common ground. We see this in Of Men and Gods and Mud, which treats mud as the ground zero of creation—a site from which so many cultures locate their origins.

ACFrom the beginning, the project in Sudan was meant to be a video installation and a fiction film, and we started shooting in 2019. Then there were the first demonstrations against President Omar al-Bashir. We were there when he was arrested and we had to leave the country.

At the time, I just wanted to document the work at the brickyard. We were just shooting whatever was happening without interfering. Then we tried to come back in 2020, but Covid-19 happened, and then we went back in 2021, when we had to shoot everything again because some people had left. It was easier to start from scratch. I ended up with hours of footage from 2019 and all this footage from 2021, which captured the time under Bashir and post-Bashir.

Whether creating films or sculptures from archaeological fragments, my work is about finding solidarity in the pain of others...

With these documentary images, I wanted to set the ground literally, as you said; to create a conceptual place from where the work would start by looking at mud in its historical dimension of being present within so many founding mythologies from Adam and Eve to Gilgamesh.

But in terms of creation, mud is also completely anchored to contemporary modes of production, of labour, of making these bricks, of making something to literally build from.

SBThis idea of mud linking ancient, historic, and contemporary modes of production feeds into the sculptures you created as part of the Of Men and Gods and Mud project, where mud bodies are formed to support the ancient heads you collect. Could you talk about that?

ACIn my work, fiction and sculpture emerge from the same ground. I had these heads without bodies in my studio, and I started to think about the kind of body that mud could give to them. I thought about how humanity has always seen mud as a place where other creatures arise and take form, and how a body of mud could bring these fragments to life, turning them into characters from mythological stories.

But there is another aspect to these sculptures that is important to point out. For me, the starting point for these sculptures is the auction house where I acquire the artefacts I use, and the endpoint is when the sculptures I create with them enter the museum. To me, these objects are in the private market because they're considered not important enough to be in museum collections, so I take them from the market and sneak them back into the museum camouflaged as contemporary art sculptures.

The questions these assemblages raise are the exciting part. There are always long discussions that go with their acquisition. Museums are very careful when acquiring work containing artefacts because they have to be mindful of their origins and how they were obtained. Since I only buy from the legal market, I have legal papers for all of them, but while I never question what is written in the legal market, there are lots of fakes. My idea is that whatever the system is telling me, that's it.

These artefacts also open up questions about whether my sculptures are considered contemporary artwork or a collage of contemporary and ancient, which affects what departments they belong in. This also connects to the issue of conservation. How do we conserve the ancient components of these compositions and the rest of the sculpture?

SBYour approach to artefacts follows the same logic as your films, in that these artefacts become recontextualised through their relocation into a new conceptual framework, just as your films begin from a context and move into fiction. That process transforms reality into something universal, which circles back to how your work seeks common ground...

ACWhether creating films or sculptures from archaeological fragments, my work is about finding solidarity in the pain of others; to create a community of broken bodies that come together in solidarity. That's why I like to call my sculptures 'graftings'. In botany, you can graft two species by connecting them with rope so they start growing together.

When I go to any context shaped by tough histories, I'm interested in finding links, because I also come with this same baggage. I want to find a space where we can talk to each other because even if we have different experiences, we also have shared references and questions.

That's how I deal with it. We all come from a place of suffering and hardship, and we all carry our own stories. We also try to find connection and meaning in our daily lives. So in terms of my work, I come with my own wounds and I look at your wounds and try to make something out of it.

The wound has always been very present in my work. It's a leitmotif that I go back to because the wound is also a place of permeability between inside and outside. It's a meeting point. You can spill your guts out of these open bodies or you can let the world outside look inside.

In The Dam, the main character carries a wound with him throughout the film. There's a scene at the infirmary where the nurse is putting medicine on this open wound, and it feels like someone's getting into your body. It references St. Thomas, who puts his finger into Christ's wound—there's this whole iconography around the wound as something that we come in and out of.

SBHaving navigated different geopolitical contexts, what have you learned about your practice as an artist and filmmaker over the years?

ACI think what we do as artists or filmmakers is that we create the conditions for something to happen that's beyond us. We make things visible.

In terms of how I navigate different contexts, I think if you are genuine about the approach, it'll be fine. I'm totally against this idea that you cannot make a work about a place because you are not from there. It depends on how you approach it, what you do with it, and the respect you have. It's a tricky and very thin line to walk on. But I'm willing to take the risk. —[O]