Mounira Al Solh: How to Live Musically

Sponsored Content | Zeno X Gallery

Mounira Al Solh. Still from the video portrait Mounira Al Solh: Lovers, Nahawand and Saba (2022). Courtesy Zeno X Gallery.

Mounira Al Solh. Still from the video portrait Mounira Al Solh: Lovers, Nahawand and Saba (2022). Courtesy Zeno X Gallery.

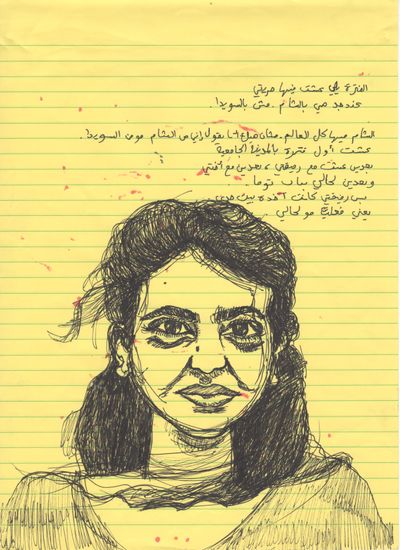

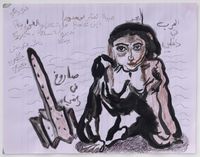

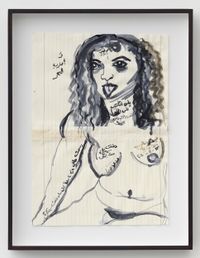

For documenta 14 in 2017, Mounira Al Solh created a series of portraits on notepaper, using ink, marker, graphite, paint, and thread, to amplify each sketch into both document and drawing, with notations in Arabic attesting to the lives of her interlocutors.

'I Strongly Believe in Our Right to Be Frivolous' is an ongoing project first conceived in 2012 as a series of 'time documents' of the 'Syrian and Middle Eastern revolutions and subsequent crises', writes curator Hendrik Folkerts. The portraits were started in Beirut and were continued, among other cities, in Kassel and Athens, where documenta 14 had been split. Each image depicts refugees and migrants who escaped war or oppression.

As a whole, the project 'approaches the topic of (forced) migration on the level of oral history: an ambiguous historiographic category that escapes more formal archival processes', Folkerts continues, 'yet an undeniably tenacious one because knowledge is conveyed through people themselves.'

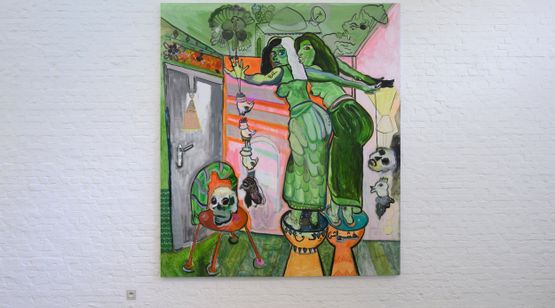

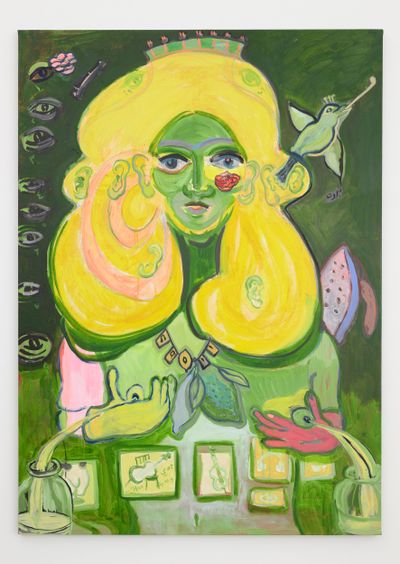

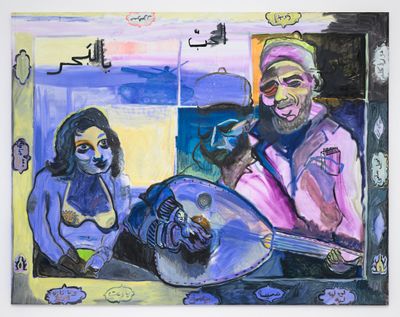

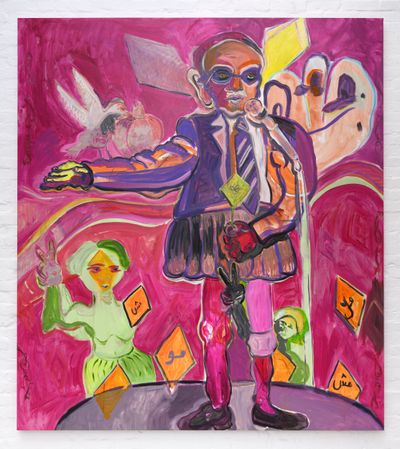

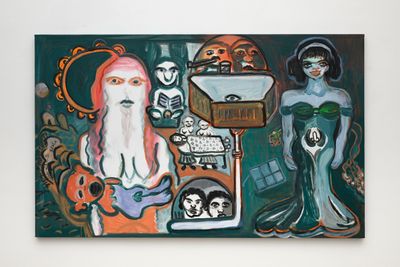

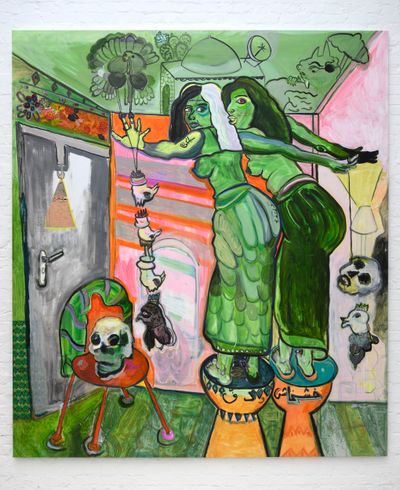

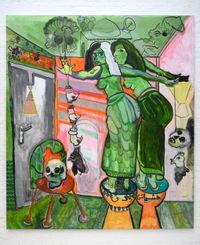

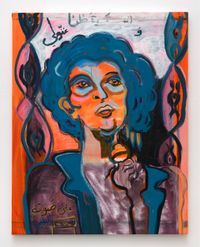

This idea of an embodied, material transmission extends to the artist's latest solo exhibition with Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp, Lovers, Nahawand and Saba. She sang me songs and I didn't mind (30 November 2022–28 January 2023), where a new series of paintings treat music as a prism through which a kaleidoscope of associations emerge.

Working from her studio in Beirut to a playlist that not only invoked particular histories, but threaded them together, Al Solh reflected on the potency of music as a mobilising force, transmuting the sounds of singers like Fairuz, who became at once the voice of Lebanon and the pan-Arab region, into paintings that reflect on the complex, sonic responses to the times in which particular songs were sung.

The result is a series of expressive compositions on canvas in which Al Solh responds to the music she has heard with a liquid accumulation of strokes and shades, building up figures and scenes that are as uncanny as the colours used to render them, as if invoking the illuminated tones of Degas' captures of Montmartre by night.

Al Solh admits the paintings composing Lovers, Nahawand and Saba are personal, despite their connection to meta-narratives surrounding the history of her native Lebanon, and the Arab world more broadly, not only in the 20th century but in the evolving 21st.

Weaving stories and registers, however, is something of a hallmark of Al Solh's multi-disciplinary practice, with its articulation of expanded and enmeshed perspectives across time and space, such that a painting is never a painting, but a note in a larger score exploring the bearing of the past on the present.

The artist's recent solo at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, A day is as long as a year (2022), for instance, centred around an installation that takes its form from the Qajar-era ceremonial tents of Iran. Created with women embroiderers from Afghanistan, Iran, Lebanon, Turkey, South Africa, and the Netherlands, the henna-tinted hemp structure is intricately patterned with embroidered flowers, birds, and Arabic words on the outside, while inside, larger panels hanging in the centre recount stories of loss, resilience, and hope.

Under the tent, a sound installation recites the same Arabic words describing happiness and sadness, uniquely hand-embroidered by the artist. The audio, voiced by Lebanese singer Rima Khcheich, is mixed with the recording of two Iranian women singing Iranian songs they associate with mourning.

The tent form, this time, red and yellow, was likewise a focal point in Al Solh's 2019 exhibition with Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut, The Mother of David and Goliath, with Mina El Shourouk ila Al Fahmah (Lackadaisical Sunset to Sunset) (2019) embroidered with contemporary testimonies of oppression experienced by women, in addition to instances of female empowerment in Islamic history.

There is a sense of intricate interrelation in Al Solh's body of work, with paintings, drawings, recordings, and other forms of expression combining to create a visual score that explores communication as an expanded field.

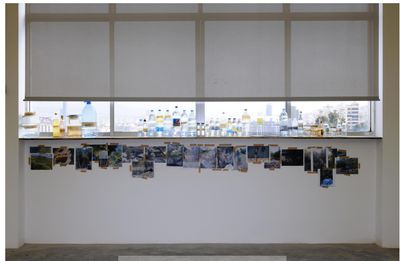

Take The levels of Thirst (2019–ongoing): 39 plastic water bottles of undulating sizes are arranged in a line, filled with water from various sources in Lebanon and Syria, from polluted rivers to drying wells. Behind these bottles, words by 11th-century Persian scholar and poet Al-Tha'alibi describe different forms of thirst, while images of each water source are pasted in a row below this display.

From a background in music to a deep exploration of how culture transmits itself through spectrums of experience, Al Solh elaborates on the dynamics at play in her work in this conversation, which focuses on her latest music paintings. What emerges is an intellectual and intuitive process that filters deep research into expressive compositions that tap into art's capacity to challenge the way the world is understood.

SBCould you introduce your latest show with Zeno X Gallery?

MASThe exhibition is titled Lovers, Nahawand and Saba. She sang me songs and I didn't mind, and it's showing a series of new paintings inspired by various moments of listening to music. The title borrows from the name of scales in the Arabic repertoire of music, which we hear less today within pop music. Their words are in Turkish, Farsi, and Arabic.

The series is about music, but it's also about the meaning connected to every song.

I am very inspired by scales that have a quarter tone, which doesn't exist in Western scales. I actually studied music in the past and played the double bass in a band. The songs we played were based on Turkish, Farsi, or Iranian scales. But slowly, I stopped wanting to be a musician.

SBHow did you make the transition from musician to artist? Was there a eureka moment or specific project that cemented this turn?

MASI drew and painted since childhood and played instruments on and off, including the classical guitar. At school, we were lucky to have Lebanese artist Greta Naufal, who transmitted her passion for art to us!

In her class, we were encouraged to listen to music, make collages, and paint, while studying other painters. She had a very contemporary approach and assigned amazing projects. Once we salvaged wooden window frames from old houses in Beirut during the reconstruction that followed the war and re-painted them.

Greta is also our neighbour in Beirut and I've been to her house a few times to draw with Patitucci's music in the background. In my youth too, I always painted at home and listened to music with my brother, a DJ.

We were many at home, so I had to wait for my family to fall asleep and woke up at night to make huge painted drawings. In the morning, they liked to come and see what I did and tell me their comments. In other houses, we were not allowed to paint or make a mess, but my mum and dad both loved music and art, and they transmitted their passion to us.

As children, we were the only ones in the building allowed to draw on our bedroom windows. All the neighbours came and we made a collaborative drawing, alongside my cousins. As a teenager, I did cross the line sometimes, but in general, I was really encouraged.

I didn't want to go to a private university for painting. I studied the double bass at the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music and borrowed the instrument from a friend of a friend. When the bass had to return to its owner, I panicked because I was very attached to it. In Beirut, it wasn't easy to find a bass to practise, so I stopped abruptly.

I switched to cello because I could find an affordable one, but the teaching method was so bad, it made me hate studying music. At that time, I was drawing and illustrating Al Laylatou Ba'd Alf Lyla wa Layla (The night after one thousand and one nights), a book written by Mounir Abedallah.

I was also doing my own paintings on paper, so I thought to continue my passion for drawing. Then, around 1997, friends introduced me to the acclaimed Lebanese artist Hussein Madi, who gave me drawing lessons in his studio. After a year, he convinced me to continue studying at the Lebanese University, so I did a few exams until they accepted me there.

For me, there is no difference between being an artist and a musician, even though they are two completely different practices. Music always comes into my work, somehow.

SBWithin the context of your practice, where would you locate this new series of paintings? Why did you decide to paint music?

MASBy working on this exhibition, I got into music again and this time I found it from a different perspective. Painting in my studio is also very physical, and dancing or listening to music as a warm-up is part of it.

I am interested in Arab musicians from the golden age in Egypt, back when the film industry was connected to the singing world. There were a lot of musical films at the time, and if you were recognised as a singer, you would also be acting in films. To become famous in Lebanon, you had to be recognised in Egypt, so there was a lot of intertwining.

SBWhat do such songs represent to you?

MASWe all listen to that music, being Lebanese, Iranian, Syrian, Iraqi, Palestinian, Jordanian, and so forth. When it comes to songs by Umm Kulthum, the one and only Lebanese Sabah, Sabah Fakhri from Aleppo [Syria], or Samira Tawfik, the Lebanese tabla percussionist, who has Armenian roots, there are a lot of shared images in our minds and souls.

The state of being in my mind is a sort of Sufi état d'âme ascending. When this is allowed, the painting breathes.

There's an openness and fluidity in the music, too—then and now. Today, you don't need a CD player or tape to find your music, you can go online. Music is also something you can take with you anywhere you go—in exile, or outside of it, to the beach. I'm interested in finding ways to live with music, or live musically. For example, when there is war, somehow its events are also connected to certain songs or sounds.

Despite its wars so far, Lebanon has generated so much music. Lyrics that could be very trashy at times, or kitsch, but they can also be taken from poetry! They have meaning, accents, and images—so it's an endless sea of absurd or poignant matters that are connected and surprising. These songs stay in people's minds, unlike the poetry you learn by heart at school. Even if you can't write, you can learn a song by heart.

Going to school in Beirut, there was usually Fairuz playing on the radio in the car, and her music generates endless meanings. For us, it's the music to wake up and start the day to—usually the most precious time of the day. It was also like a punishment when you didn't want to hear it!

Music has this meta nature that can heal. It's a process we practised every day since the explosion.

You also feel sorry because, after the war, the nice things she sang about no longer existed. The saddest moment is when your city is bombed and someone plays Fairuz in the background.

Fairuz has outstanding songs from the war days. She has been singing for decades and her family has written hundreds, maybe thousands of amazing songs for her. Her repertoire is exceptionally rich and spreads over decades. Sabah, as I read somewhere, recorded around 3000 songs!

SBThis comes back to the idea of living musically that you mention, which taps into music as a composition of fragments or notes that people connect to create a collective sound. As you've said, it draws endless meanings and metaphors, like how to find commonality, or chorality.

I feel like this is the underlying structure that informs the composition of your work. Individual works become notes in a bigger composition that expresses a rich and material intersectionality, thereby resisting the perceived conditions of formalism as a minimalistic reduction.

An example is when you mentioned the complexities of the Arab musical scale being reduced by pop music. With that in mind, how are you interrogating this through your paintings? How were they composed?

MASIt's intuition as much as it is intellect, which is why I love the medium of painting. I also love some kitsch songs and music born during the wars—my influences are too diverse to pinpoint. What I like is the confusion of things; the state of being in my mind is a sort of Sufi état d'âme ascending. When this is allowed, the painting breathes.

Painting is a very personal thing, as opposed to the tents, or my other socially engaged works. It's the solitude I need to process everything, all these networks are in my mind.

After living through the 4 August explosion in Lebanon, it took me a year to understand the permissiveness I needed to give or tolerate for myself, to open for my own healing process. Music a component of constant healing from the things we will never heal from.

Painting is great because you can combine so much within it, from music to sociological connotations, research, anthropology, and musicology. It's very physical at the same time; the use of brush and colours is marvellous because you can go beyond the limits of say, research, and carry a lot of notions to another level through the act of painting.

SBLike a musician, you seem to conduct your thoughts to the surface through painting. Could you speak about the role of sound in your work, now and then?

MASAs I have mentioned, as a practice, I always warm up before painting by dancing or listening to music. In the tents, I always recorded voices, music, singing, connective performances, or performances on my own. Somehow, music comes back strongly, but it's also a part of you. It's meant to process, but it's also very emotional.

After that explosion in Beirut in August 2020, I think there was a need for inner recovery. Seeing your own city and neighbourhood blown, I saw my heart break. Music has this meta nature that can heal. It's a process we practised every day since the explosion. You carry the guilt of survival and the feelings are complex. Listening to music, isolating yourself, and being isolated in your studio are part of the healing process.

Telling yourself that you still have a lot of beautiful things around despite everything happening in these Arabic countries and all around is also a way to hold on.

SBCould you describe how your compositions reflect this engagement with the history of music from the Arab world?

MASIt's a process, of course. I don't know if I want to say everything because it's very personal [laughs]. I have this challenge: I don't want to portray the people I am listening to, but portraiture is a way to put it out there.

Every person or song is related to an era. For example, Ragheb Alama, whose songs accompany us in love, in dance, and on so many occasions, is from Beirut. If I'm in my studio there, I see him going to Starbucks. Or for example, Georges Wassouf, who is a Syrian singer who is enormously loved and made himself famous in Beirut.

In the Mar Mikhael neighbourhood, people have printed his enlarged photo on their cars. A day after the explosion in Beirut, someone played one of his songs loudly while passing by our street. I have since associated the song with my sadly destroyed neighbourhood sights.

Wassouf sang Umm Kulthum songs since childhood—so again, it's about these connections across continents and topics. They're as fluid as music, and there is no rigid or cold concept behind which to imprison the flashes of thought that come out in the painting.

In general, the series is about music, but it's also about the meaning connected to every song. I remember when an American ship, the New Jersey, came to Lebanon during my childhood. They bombed everything including my grandmother's balcony facing the sea.

I came back to these houses a day or two after the explosions, when everything was broken, and there was always someone playing a song. These songs carry memories and moments through time, like those of the 1980s, which connects to the 4 August explosion in my mind.

I remember in 2019, as you stood on the streets, you saw your country going back to zero; it was as if ten years of war had happened in an instant. It felt like I was in a black-and-white photograph of the war: everything was beyond black, with buildings expressively exploded.

But the most horrible was the number of people wounded on the streets. The next day, many were still bleeding, not knowing where to get stitched, or even have wraps to cover their wounds! People were still missing.

There's this connection between passion—of memories from bad times, but also nostalgia—in music like this. So for me, this work is quite autobiographical, even without being written. When Covid-19 came, it also forced us to isolate ourselves, and painting is an act I do in isolation.

SBSo when you were making these paintings, did you put on a track and let the composition flow from mind to surface? If so, what did these paintings reveal to you in the process of making them?

MASI love listening to songs when I paint—very emotional songs, like 'Wardahel Jazairiyya' from the 1980s, and this Lebanese belly-dance song, 'Habibi Ya Eini' (1993) by Maya Yazbek, which we saw on Télé Liban frequently as kids. When you go to bars, people always play songs like these. There were also amazing music programmes on TV, such as Studio El Fan, which carved some aesthetics.

The night dancing scene in Beirut is amazing. People need to let it out because there's so much happening. In a way, painting gives you the same outlet. It's like going to a bar and dancing on the tables—something you easily end up doing in Beirut's nightlife scene.

SBDancing, of course, is exemplary of music's potency to organise; as a language that brings people together.

MASThe dabke dance, I felt, really connected people during the 2019 revolution. In the first days of October, when we were on the streets, everyone held hands and did the dabke together.

I remember meeting many young boys, as we were all filming each other as a journalistic personal imprint and to share what was happening online. One of them got a phone call from his mum. He did not say he was in the revolution. Some boys wore masks to conceal their identities, because for their communities, they shall not be demonstrating.

In the first two weeks of the revolution, people were really united for the first time, and there was so much music everywhere! Women were so active and chants were so strongly improvised. Yet for some, looking from afar at the Lebanese-revolution days, it was because we danced that our revolution should not be taken seriously. After that period, it all became much more tragic and people were shouted at.

SBWhen you mentioned dabke, forms of which can be found across the Levant and North Africa through to Greece and Crete, I thought about how your works trace connections across time and space. Your tent works, for example, explore how cultural forms travel and evolve as they engage with other communities. Could you talk about that?

MASMaybe when you live very intensely, the more decades you witness, the more intertwined and playfully they mix and connect. You understand the connections more and more.

For example, now, we are all hopeful for the Iranian revolution and uprisals led by young girls, children, and people who are fed up. How many times have we shown our being fed up without anyone caring? But once upon a time, we shall succeed!

SBI asked the previous question with your project for documenta 14 in mind, for which you met with migrants in Kassel and Athens, among other cities, and sketched their portraits.

Given your work explores the enmeshments of geopolitical space-time through the prism of culture, could you talk about how this project sits within your practice? What was your experience navigating Kassel and Athens within documenta?

MASIt's an ongoing project. If you read the conversations I had with the people I drew, we spoke about everything that came to mind—music, love, food—anything, really! Music is my home wherever I go.

I cannot survive by staying in Lebanon at this moment; it's also my way to oppose the ruling people at home. I do not want them to decide my fate, my daughter's, and that of generations to come. I do not want to live in the country they stole from me. It's a stateless place being ruled with filth by force and the wrong people. This is not Lebanon. But no matter what, I love it. It is my home, they can't steal this from me.

We were pushed to find a second safer home to survive, and for me, it's the Netherlands, where I also find many inspirations! But in my case, I kept my studio in Beirut and my deep connection with the sea, rocks, mountains, as well as the people I love, and divide my time between the Netherlands and Lebanon according to my schedule.

SBReturning to your latest paintings, how would you say they extend or differ from previous bodies of work, and what horizons have they opened up for your research? Are you working on any new projects?

MASThis series is still in progress. There is so much more to it! And yes, the works I usually make are connected and ongoing. I am also looking forward to co-initiating the 5th issue of NOA (Not Only Arabic) magazine in a few months with the collective Qalqalah as guest editors and creators. —[O]