Taloi Havini: Reclaiming Space and History

In Partnership with Artspace Sydney

Taloi Havini. Courtesy Artspace. Photo: Zan Wimberly.

Taloi Havini. Courtesy Artspace. Photo: Zan Wimberly.

Artist and curator Taloi Havini was born in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville—a chain of islands northwest of Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea.

A descendent of the Nakas clan of Buka Island, Havini's father, Moses Havini, became a political leader after the beginning of the Bougainville Civil War (1988–1998), which was triggered by the unequal distribution of resources, ethnic cleavages, and other factors that arose from the Panguna copper mine, which opened as a subsidiary of the Australian Conzinc Rio Tinto in 1972.

Having closed in 1989, threats to reopen the mine have been murmured in recent years. The region's violent recent history looms large, and Havini—who is currently based in Sydney, her family having sought refuge in Australia in 1990—has produced a body of work spanning photography, sculpture, immersive video, and mixed-media installations dealing with colonial history, human rights, and environmental issues in Melanesia, along with material culture and the transmission of indigenous knowledge systems.

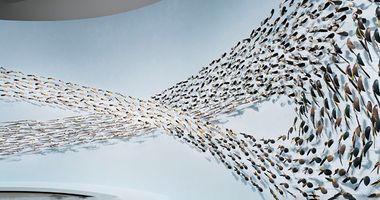

For Sharjah Biennial 13 (10 March–22 October 2017), Havini presented Beroana (shell money) (2015/2017)—a suspended spiral up of porcelain, stone, and earthenware discs, gradating from tones of earthy terracotta to cream. Replicating the shell-based currency of beroana in materials extracted from her home region, Havini references the extraction of natural resources for the cash economy. Traditionally, beroana are passed through generations and hold sacred importance, stored in vessels stowed in out-of-reach places, used in ceremonies, and worn as adornments.

In another body of work created with photographer Stuart Miller titled 'Blood Generation' (2009–2011), the violent extraction of natural resources is forced into the present—the dark grey, devastated landscapes surrounding the open-cut Panguna mine foregrounded by young residents of Buka.

A connection to land was explored in Havini's first Australian solo exhibition, Reclamation at Artspace Sydney (17 January–23 February 2020), an iteration of which then travelled to the Dhaka Art Summit (7–15 February 2020). An eponymous installation, created with members of Havini's matrilineal clan, referenced knowledge-sharing and customary designs that are used for specific, temporal architectures. On the floor of this structure, Havini laid earth upon the ground to 'create an uninhabitable surface' in reference to the still-uncertain present.

Also on view in the exhibition was Habitat, a four-channel video installation that the artist began in 2015, after she was given access to the National Film & Sound Archives of Australia, where she obtained footage of Australian presence in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. Fusing archival footage with film excerpts of her own clan and family, Havini once more presents a collision of past and present.

In this edited transcript of a conversation that took place at Artspace on 19 January 2020, Havini and Ruth McDougall, curator of Pacific art at Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, discuss reclaiming land, intergenerational knowledge, material history, and other themes present in the artist's work.

RMI'd like to begin with the idea of welcome. In the Pacific, welcome is a particularly important thing. In Aotearoa, when you are met by a Maori hongi, you are greeted by coming very close, in a nose-to-nose context, so that you can share breath—the thing that sustains all of us.

I remember on my first trip to Bougainville, when I got to the first village in Buka, I was met by a group of women standing in a line. They were carrying small containers of water, which they then poured over my feet. I was wondering, Taloi, if you could tell us a little bit about that ceremony and what it means? I remember at that time thinking both about the act of cleansing, but also my connection to the earth.

THWe call that a 'tsutsu' ceremony. It means that land is sacred. As you're coming from Australia, we realise that you're bringing spirits of other lands on the bottom of your feet. So, before you can come onto our land, we ask you to remove your shoes. Sometimes we don't care—we just throw water over you. If there's an important minister, they don't want to take their leather shoes off, for example. But for us, it's symbolic. I went to Vancouver Art Gallery for the Transits and Returns exhibition (28 September 2019–23 February 2020) and we went on some really sacred tribal lands in Sabretooth. I was completely cleansed coming back on our lands.

RMUpon entering Reclamation, we're welcomed by an image of water, and this very intense blue colour. The blue, for those who don't know, could simply be the blue of beautiful tropical waters from islands in the Pacific. However, it does have more sinister connotations. I was wondering, Taloi, if you might be able to talk a little about this colour, what it is, and the ongoing significance it has?

THThey are photographs that I took in the heartland of Bougainville, which looks right over running water. The colour also refers to the process of copper leaching, which involves dissolving copper into copper sulphate, which is bright blue. The colour brings people into the materiality of what is so integral to the Bougainville story.

There's this conspiracy theory that James Cameron made Avatar based on Bougainville; you know, the blue-skinned people fighting for their land.

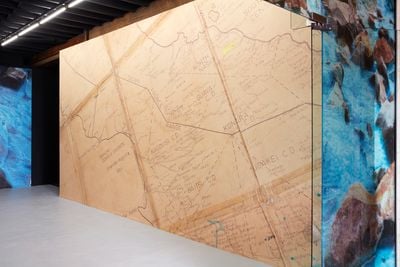

RMI have read, also, that if you swim in the Jaba River, which is downstream from the now-defunct Panguna mine, your skin can turn blue. These images—which are photos of bright blue copper leaching in the polluted rivers of Panguna—have been enlarged as two wallpaper surfaces and applied like a layer of skin to the exterior of the glass entrance that leads us inside Artspace. The wall behind the glass entrance depicts another image of the same bright blue copper leaching, while an enlarged, cropped colonial map of Bougainville is spread entirely over a built wall that creates this in-between space, separating the two installations, Habitat and Reclamation. The map also has a similar colour to skin.

I was wondering if you might talk a little about the relationship between the body, skin, and the land for you and how it's important?

THThere's this conspiracy theory that James Cameron made Avatar based on Bougainville; you know, the blue-skinned people fighting for their land. The original map is only about 60 centimetres by 1 metre, and it has been blown up. A good friend of mine in Canberra called Melissa Howe works with archives, and I put it in the post and sent it to her. I asked her to scan it to the highest resolution she could.

The idea was not to show the map in relation to where Australia is, or where Sydney is, or for viewers to locate themselves in relation to these people. The idea was to look at this Australian colonial map of Bougainville. It's blown up so much that when you really inspect it, you can see how an external government has named places like the 'Crowned Prince Range'. The people living there don't call it the 'Crowned Prince Range'. Then there are all these places where you can see someone's stroked out the name and written their own version. There are certain highlights and circles. It's about the idea that Western mapmaking is contested, and that indigenous people don't delineate boundaries on an aerial perspective as if it's used as a tool. There's that aspect to it, and it's torn—it's got holes in it. It has travelled and it has a story.

Looking at the relationships between Australia and Bougainville, mapping has been integral and contested all along—especially with the line that cuts Bougainville from the Solomon Islands and lumps it with Papua New Guinea. This was done at a time when Bougainvilleans were looking to be independent. People refer to the Panguna mine as the 'catalyst', because it was the catalyst for the Bougainville Civil War.

RMI understand that the map was your fathers. In what ways did he use it? Was there significance in using the map in reference to the other works in the show?

THYes. I'm interested in intergenerational knowledge—how knowledge is passed on and shared; how you inherit the things you had no choice in; what you learn to discover yourself. So, the map is really about how the West looks at land and space, whereas Reclamation came from a play on the words 'claim to land and country'. My father talked about how in our traditional architectures, there is a claim to land and country—they are firmly in the ground, using natural materials, and each post refers to a lineage. My generation is going through a reclaiming of space and history, because we're also deciding on the future right now.

I'm interested in intergenerational knowledge—how knowledge is passed on and shared; how you inherit the things you had no choice in; what you learn to discover yourself.

RMYour immersive video Habitat was also shown at Artspace. This is a work that looks at very different perspectives and intentions towards land in Bougainville. It brings together the colonial archives and new footage. I wanted to ask about the use of the colonial archive and why that was important to engage with—not only with the material, but also with the history that material has created here in Australia, and even internationally.

THThe video contains 1960s footage from the ABC, showing a man pulling a female protester from Rorovana village in Bougainville. At Artspace, I presented the last iteration and a four-channel installation of Habitat. Previously, it was three-channel, while the very first video installation in 2015 began as single screen.

Habitat, for me, is like an ongoing commitment to document Bougainville, starting with the catalyst of the mine, and broadening out to the coastal areas of where I'm from in Buka Island, in the northwest. The first iteration was really an exploration, after a friend of mine whose maternal land was destroyed by the mining tailings suggested that I go and see her aunt Lucy, a traditional landowner from Konawiru, who told me about the environmental damage. I went to the end of the mine site, where the tailings are and I just thought, wow this is pretty big—the damage, the stories... So the older version was really a poetic version from the tailings into the actual pit of the mine, following another matriarch and landowner who has been panning for gold, called Agata.

By the time I wanted to make another one, I realised I hadn't dealt with history. I knew a lot of that history was actually in Australia, in the Australian archives. I spent a lot of time scrolling through the National Film and Sound Archives for anything to do with Bougainville, and I distilled a lot of film footage, including a propaganda film that was pro-mining called My Valley is Changing, along with ABC news footage from the nineties showing Papua New Guinea military presence in Bougainville. These chapters of history from the sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties, were really important for me to use, along with my own footage of my family in Bougainville.

RMSome of the archival material is from your family archives, both from your mother and your father. I was wondering if you might be able to tell us about the inclusion of that material?

THThere is footage from my father's Hi8 camera, recording the first president of Bougainville, Joseph Kabui. In 2005 we got our own government, the Autonomous Bougainville Government. After compiling all of the history and getting very depressed, I thought it was very important to have images that come from our perspective, rather than films about or on us by the West. I was fortunate to receive some funding to purchase the copyrights to use the archives and do some digitisation of my father's archive. The first thing I did was digitise old tapes from my father's archives. I had no idea what was on them. When that footage came through, I just thought: this is really important footage and it has to be in the story of this archive that I'm creating.

My parents worked together as a team in life, and my mother Marilyn helped my dad by compiling and administratively writing human rights abuse compilations that were coming into the house from Bougainville, dated between 1989 and 1995, including statements such as 'I lost my brother to this PNG soldier', 'rape victim here', or 'house burning here', and so on. Any kind of human rights abuses were sent to the house. I was probably about nine years of age. The list appears in Habitat, at the same time as we see scenes of conflict. It was important to have my parent's archives in that story.

RMHabitat was first presented in the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9) (24 November 2018–28 April 2019), as part of a project called Women's Wealth, which looked at the strength of women's practice in Bougainville and in the Solomon Islands. It was presented alongside a group of really beautiful textiles and adornments, and other hanging works by women from Bougainville and the Solomon Islands. I'm just wondering if you might be able to tell us, what aspects of this work did you see jumping off of and continuing the story that was being told in those works?

THWomen's Wealth was absolutely integral to telling the story of Bougainville and the Solomon Islands—how we are matrilineal people, as opposed to the patriarchal ways that land and inheritance are passed along. We inherit through the mother's line, or through the father's female line, so there's this idea that the mother would nurture for the land. Through that, ideas of wealth are questioned—not just material wealth or economics, but that we are a people and culture that has other ideas of how to be full, and these ideas run our relationships, land, and so on.

It is very patriarchal to say, 'This land belongs to the Crown, we're going to go in and just take.' In Habitat, there are scenes of women wearing headdresses, which are made from pandanus and stitched and sewn into hoods called 'tuhu' in my language. These are symbolic for us, because every woman wears them, starting as a baby and through marriage and funerals. They're also practical and waterproof, used as protection from the rain and sun. You know, if we go into the garden and it rains, we put our tuhus on. Or if we have a child, we put them in it, since it breathes and is nice for them.

RMHabitat begins with a woman's voice speaking in the language from central Bougainville. Would you be able to tell us a little bit about what she's saying and how that frames the work?

THI have to credit Kuntamari Crofts, who lives in Sydney and is a Nasio-speaking Bougainvillean and allowed me to go back and re-edit the 1970s film and give that woman her voice back. In Habitat, there's a scene where an Australian patrol officer is waving around a scrolled-up map, and he's basically using it as a weapon. He's saying, 'Well you people are ruined anyway, what's the point?' And the woman says, 'No. I always be here.' Knowing what she said, it was really important to put that in the centre.

As the editing process went on and got its own personality, I thought, if I'm going to visually represent women from Nasio—where the Panguna mine sits—it will be important for audiences to hear the language. So I asked Kuntamari: 'What would you say today?' We watched the footage together, and she sat with the sound designer and said whatever came naturally to her in Nasio, which is: 'I will always be here. This is my land. Where will we go? We'll always walk this land. This is our land.'

RMThe sound is quite a significant part of the work. In fact, within the context of the display at Artspace, you heard the work before you viewed it. Can you talk a little about the importance of sound in all of your videos?

THWhen you purchase copyrighted footage from the archives, they don't give you the music rights or score. You have to get a separate licence and pay if you use sound and music for that. I thought that was great; I didn't want their colonial sounds. It was actually frontier music. It just didn't represent who I am and how I view my history and my place, being both Australian and Bougainvillean. To silence it was already satisfying. Then, I was picking out the bits where, for example, a man says, 'Our share will be 20 million dollars' to mining executives in a boardroom. To this day, I still don't know whether they're acting, or if it is a real boardroom with shareholders.

I worked with sound designer Michael Toisuta for the sound. We spent a long time talking about the topic and its history, before we started sitting down and working together. The sound had to hit you in the chest and take you on a journey of feeling really heavy and elevating you at some points to deal with what you've just seen. I think Michael worked really well with getting that feeling.

RMThe inspiration for the Women's Wealth project in APT9 came from a dream shared by you, Sana Balai, and Marilyn Havini to make creative opportunities available to women in Bougainville. Quite a significant part of the making of this work also entailed you working at home with members of family and clan, taking archives back. I was wondering if you could talk a bit about that process and its ongoing importance in your work?

THYes. I went home over October and November for the referendum vote for independence from Papua New Guinea. I also took all of the archives over, and we did lots of screenings in the village. That was the first time that people had seen all of this footage; they had no idea that there are lots of films about Bougainville in Australia. The process is just as important as anything. I'm always accountable to my family in Bougainville. We have to involve each other in the process; there can be no surprises and if they're happy with it, then we can go forward. This work has never been seen in Bougainville at this scale. We have no galleries, no contemporary spaces; we have one projector in the community hall.

It's important that before I go and show it in other places, there are huge discussions around it. My mother is always involved in the discussions around the archives that I'm constantly data mining from her and dad's house in the village. I think the relationships are important. My sisters, cousins, and uncles are all involved. Those aspirations also inform Reclamation.

RMReclamation returns audiences very physically to the land. I was wondering whether you might be able to talk a little about why you wanted your audience to come back into this very raw material engagement with those ideas?

THA large part of my practice is site-specific, and I know that term gets used a lot, but it really is important. This work started in Bougainville—in many ways that is due to the fact that I was born there and had all my experiences there, so it's an amalgamation of that time and my time in Australia. Habitat was a really hard work to make—to confront history and put all the faces of patriarchy mixing in with the matriarchy as well. At Artspace, I wanted to create a work of contemplation and a space for thinking differently about how knowledge is shared and passed on, as well as thinking about space and impermanence.

Without monuments, impermanence actually creates and keeps knowledge alive through the act of rebuilding.

RMThe cane structures at Artspace were a nod to the work that you showed in Dhaka, and that were created at home in the village with members of your clan. I was wondering if you'd be able to talk a little about the process behind Reclamation?

THOur formal and traditional architectures are constructed in a way that depends on what happens in the space. I know that someone from my language area, Hako, would come in here and look at certain works and say, 'That is a garamut design', or, 'That is a reki design', and that brings me great comfort, because this has been specific to our ideas of mapping and where we are in the world.

As a contemporary artist, I get commissions and take work to other places in the world. In the case of Reclamation, I said to my clan members, 'Hey, I'd like your involvement in this particular work'. Together, we built a contemporary structure based on these very old ideas that we've inherited over time. I had a crew of cousins, uncles, sisters, and aunties. This included, I'd like to acknowledge, Aunty Sana, who lives in Lontis village, which is not far from mine. Our families have connections and we have a special relationship—she acts as both a mentor and a friend.

Since I work with video, film, photography, sculpture, and installation, I'm very much a contemporary artist back home. When talking to my family about the work, it was principally about the ideas and not the forms. We don't have monuments in Bougainville, but we do have structures. That's what I talk about in the ideas around what permanence means—we build for a purpose and for a limited time, and then we gather again and deconstruct the architectures. If natural elements destroy it, that's ok—we'll build it again. Without monuments, impermanence actually creates and keeps knowledge alive through the act of rebuilding.

Everyone back home was excited by the idea of making these forms collectively for iterations at Artspace and Dhaka. In a way, the process of lashing and binding the cane into panels with my clan members was sort of like having a contemporary art centre under my house—going to the jungle, harvesting the cane, putting it together, and so on. So that's sort of how all of this came to be, except for the soil. Having 17 tonnes of soil here was to create an uninhabitable surface to reflect a kind of uncertainty that we are experiencing, or the uneven terrain that we're standing on right now.

RMYou have very poetically described these structures as well as maps. Could you elaborate a little on how the cane sculptures are considered as kinds of mapmaking, and how they operate in comparison to the maps at the beginning of the exhibition space?

THThe negative spaces in the structures suggest ideas of flight. The panels were placed in a larger structure at the Dhaka Art Summit that was itself a form of chart. We started making, twisting, and lashing, and when we knew that it was finished, we held it up to the sky or horizon. That's how certain kinds of navigational tools were made across the Pacific for long and short ocean voyagers: by placing certain sticks together and arranging them so that you could place your vessel in relation to other elements, like the currents or trade winds. These also reference mapmaking and navigation in Oceania.

So, when we held up our cane frames with our lashed compositions, we were in a sense creating a representation of our worldview in relation to each other and our natural habitats. In the first instance, after we collectively completed lashing one of the cane structures and held it up, Aunty Sana said, 'Oh, that's a reki!' Reki is the word for flying fox, which is my totem. That was a beautiful and intuitive outcome, to acknowledge our ancestral totem, the flying fox.

That first work then set the basis for more formal and less formal cane structures that were in a sense forms of us 'drawing' with sticks of cane and lashing them to form individual frames, which you could find at Artspace in the form of a free-standing installation in a room covered in soil or an 'uninhabitable' surface. —[O]