Acts of Survival: Art in Beirut after the Blasts

Vartan Avakian, Short Wave, Long Wave (2009). Exhibition view: Water, Marfa' Projects, Beirut (21 May–31 August 2021). Courtesy Marfa' Projects.

It has been nearly one year since Joumana Asseily's gallery Marfa' Projects was closed due to the catastrophic explosions set off by ammonium nitrate stored in the customs area at Beirut's port district. Marfa', which means 'port' in Arabic, was immediately destroyed.

Luckily, no one was there when it happened on 4 August 2020. But the gallery was reduced to rubble and shards of glass: an image that continues to characterise Beirut, a city long revered as a capital for art and culture in the Middle East.

On 21 May 2021, ten months after the blasts, Asseily decided to reopen the gallery with a group show, Water (21 May–31 August 2021) as part of an international collaboration with Galleries Curate: RHE, presenting works by artists from the gallery's roster.

In Lebanon, 'compounding crises have blocked our horizons', wrote Asseily in the invitation. 'It is not in spite of the circumstances, but rather with them in mind, that we have decided to reopen ... in a neighborhood that was destroyed but is still home to all Marfa's artists.'

While much of the debris has been cleared, buildings damaged or destroyed from the port blast can still be found. Either next to collapsed or bullet-holed structures—remnants from Lebanon's violent past, including a brutal 15-year civil war—and those newly decimated structures abandoned from the process of rebuilding due to lack of cash or a tenant or property owner that fled the country seeking a better life.

Husks of their former state, these destructed buildings recall Lebanon's current woes as the country plunges into some of its darkest days in history.

If life was a challenge in Beirut before, it has become even more so now. The World Bank recently called the situation among 'most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-nineteenth century.'

As the value of Lebanon's currency continues to fall owing to the economic shock of the pandemic, Lebanon's collapsed economy, and the aftermath of the August 2020 port blast, basic necessities are scarce and extreme poverty is on the rise.

Deliberate inaction from the government means the country is facing a prolonged state of depression, with no solution in sight. Those who can—among them members of the creative community—are fleeing the country, following in the footsteps of the previous generations who escaped war.

Artist, curator, and publisher Abed Al Kadiri is one of many Lebanese professionals that have recently left. He moved to Paris and was offered a studio in the Cité Internationale des Arts by the Al-Mansouria Foundation for Culture and Creativity. He's only just starting to produce work again.

Those who remain are engaging with a variety of projects. Beirut-based photographer Dia Mrad has been photographing for the Beirut Heritage Initiative, Together Li Beirut, MARCH, and other NGOs, in symbolic rates, and has now shifted to short-term contracts and daily shoots.

While last year's many fundraising initiatives, organised locally, regionally, and internationally, contributed greatly to Lebanon's efforts—including its arts and culture sector—to rebuild, more cash is still needed to bring back to life Beirut's institutions and heritage buildings.

The artist recently had a solo presentation at Arthaus, a boutique hotel and exhibition space, in The Road to Reframe (16 June–5 July 2021). His photographs include surreal portrayals of Beirut, particularly the destroyed silos in the port from where the blasts took place. On 3 August, the artist will exhibit in the Grand Hotel du Cap Ferrat as part of a gala dinner to raise funds for Sursock Palace.

Local and international entities also continue to assist artists. Ashkal Alwan – The Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts, a non-profit organisation that promotes contemporary art practices in Lebanon, in addition to the French Ministry of Culture, have helped to find dozens of Lebanese artists residencies abroad.

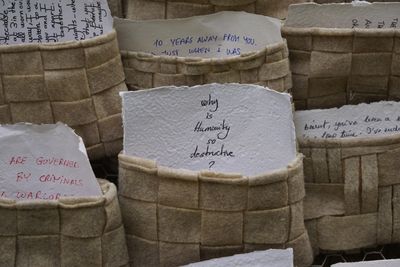

Lebanon's multiple crises have also fuelled artistic production. Lebanese-Polish architects and sisters Tessa and Tara Sakhi, who run the multidisciplinary architecture and design studio T SAKHI, have created a poignant installation running parallel to the Venice Architecture Biennale (22 May–21 November 2021) titled Letters from Beirut: a six-metre wall of 2,000 handwritten letters to Beirut from Lebanese citizens.

'The installation is our way of contributing to the preservation of Lebanon's collective memory,' say the sisters. They too say there are no work opportunities for them in Lebanon today.

While last year's many fundraising initiatives, organised locally, regionally, and internationally, contributed greatly to Lebanon's efforts—including its arts and culture sector—to rebuild, more cash is still needed to bring back to life Beirut's institutions and heritage buildings.

Organisations such as Beirut Heritage Initiative, a consortium that aims to gather funds for the rehabilitation of heritage buildings, the Aliph Foundation, UNESCO, Beit Barakat, Live Love Beirut, and Bebw'shebbek, continue to raise funds to bring the city of Beirut back.

'For the moment the funds they gathered really serve more to reinforce the structure of these buildings and make sure they don't collapse rather than rehabilitate them as the costs are huge,' says Zeina Arida, the director of the Sursock Museum, one of Lebanon's prized cultural centres.

For institutions in Lebanon's capital, life is also a day-by-day existence, but a stroke of good news came for Sursock in June when the Italian government and UNESCO signed a funding agreement of USD1.2m out of which $965,000 is going to the refurbishment of the museum through the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS) and UNESCO's initiative Li Beirut.

The Sursock Museum, housed in a 19th-century mansion that only completed a costly restoration in 2015, is shy of around $600,000 to reach its target of $3 million to completely rebuild and reopen, which Director Arida hopes to do by April 2022. But until it receives the funds it is difficult to commit to the future planning of exhibitions.

There is some positive news on the horizon, with the museum in discussions to loan some of its famed works to a big art organisation (name still under embargo), but for now the focus is on surviving each month.

'There's just not enough cash in the country,' says Arida—something that gallerists are also navigating as they reopen. For gallerist Saleh Barakat, who lost a member of staff, Firas Al-Dahwish, during the explosions: 'A bit of everything is allowing us to survive locally and internationally, these days.'

Amid the catastrophe, life goes on, but that doesn't mean it goes back to normal.

The museum is struggling to find fuel to keep the AC going in its artwork storage facilities—in Lebanon, electricity routinely shuts off for hours in a day due to dysfunctional political management. Generators, which the Lebanese rely on for when the lights go out, are operating 20 hours a day, Arida says, if not more, and fuel costs are rising. It's now become a common sight to see long queues of cars awaiting petrol—sometimes for less than quarter of a tank.

Barakat's strategy to survive is to sell his old stock of paintings to international clients or art auctions while launching new Lebanese artists in a country that can only sell within its present complex financial system of 'lollars'—a Lebanese dollar is a U.S. dollar stuck in the banking system when it collapsed, with no value outside of Lebanon—and Lebanese pounds, whose value continues to plummet.

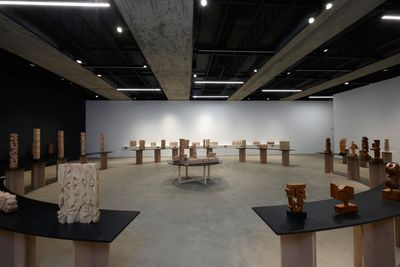

To sustain both Agial Art Gallery, which he relaunched in October 2020 with a show by Lebanese artist Bassam Kahwagi, and his larger space Saleh Barakat Gallery, which reopened with a solo by Lebanese artist Hiba Kalache in December 2020, Barakat is collaborating with entities in Europe and the U.K. to bring high-value 'fresh' U.S. dollars into the country.

The gallery also participated in the first edition of MENART, a fair run by Laure d'Hauteville, the founder of the Beirut Art Fair, dedicated to Middle Eastern art staged in the Paris capital in May 2021, with Galerie Tanit, founded by Naila Kettaneh-Kunigk and Stefan Kunigk, also taking part.

'For us the most important thing is to survive the three coming years with dignity and pride and sustain our artists until this dark cycle finishes and we can start a new cycle,' said Barakat.

Prominent Beirut-based collector Tarek Nahas is doing his part by buying works by Lebanese artists and initiating collaborations for them that he hopes will come to life soon.

Additionally, auction houses in Lebanon, notably FA Auctions, Nada Boulos Auctions, ArtScoops (an art platform dedicated to auctions online), and Arcache Auction, are active online, selling a mix of Lebanese works and those by other Arab artists.

Amid the catastrophe, life goes on, but that doesn't mean it goes back to normal. 'The art and culture sector cannot be okay because the country is not okay,' Arida stresses. 'Everyone is leaving. There is a brain drain and we are entering even worse days now.'

If a museum is a place for community and positivity, Arida continues, 'how do you make that happen in such dire times?' —[O]