Xiaoyu Weng

Xiaoyu Weng: Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Xiaoyu Weng: Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

In 2015, Xiaoyu Weng was appointed The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Associate Curator of Chinese Art at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, where Weng is working with consulting curator Hou Hanru to implement a long-term research, curatorial, and collections-building programme that focuses on commissioning major works from artists born in Greater China.

The appointment was a natural progression for Weng, a prolific curator who has organised exhibitions and public programs at such venues as the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, the CAFA Art Museum in Beijing, and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam.

Prior to her appointment at the Guggenheim, Weng was the founding director of the Kadist Art Foundation's Asia Programmes for Paris and San Francisco, where she oversaw artist residencies, built the contemporary Asian art collection, and launched the Kadist Curatorial Collaboration, which organises exhibitions designed to encourage cultural exchange. Before that, she was program director of the Asian Contemporary Art Consortium in San Francisco and a curator at the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts at the California College of the Arts.

In this interview, Weng talks to Ocula about Tales of Our Time (4 November 2016–10 March 2017), the second exhibition organised within the framework of the Guggenheim's Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art Initiative.

Shown at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the exhibition will present new commissions by nine artists born in mainland China, Hong Kong, or Taiwain: Chia-En Jao, Kan Xuan, Sun Xun, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Tsang Kin-Wah, Yangjiang Group, and Zhou Tao. In creating work for the show each of the artists responded to a challenge Weng and Hou Hanru have posed: how to represent—and respond to—the conditions of globalism when creating work that also responds to a certain kind of national frame, which in the case of this exhibition and the programme to which it belongs, is China.

SBTales of Our Time brings together artists who, as the exhibition's introduction states, 'challenge the conventional understanding of place. By portraying often-overlooked cultural and historical narratives, Chia-En Jao, Kan Xuan, Sun Xun, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Tsang Kin-Wah, Yangjiang Group, and Zhou Tao explore concepts of geography and nation-state. Their artworks address specific locations, such as their hometowns, remote borderlands, or a group of uninhabited islands, as well as abstract ideas, such as territory, boundaries, or even utopia. China, too, is presented here, not only as a country but also as a notion that is open for questioning and reinvention.'

In your introductory essay you talk about one of the greatest challenges in working on this show: how to reconcile the contemporary condition in China that is characterised by a conflicting relationship between its developing globalism—summarised by a 'cloud' mentality in which the 'free-floating individual' embraces the idea of the global community—and its own national and political character.

XWYou sum up this complex situation in a really succinct question: 'Can we diagnose and counteract the deceptive deterritorialisation enacted by the ideology of the cloud, without resorting to reterritorialisation that is, without projecting an equally false monumental and unified Chinese artistic character?'

SBCan you talk about how you sought to answer this question along with Hou Hanru, your fellow curator, in the various stages of the project, from conceiving of this exhibition theme, the selection process that followed, working on commissions, to the final installation?

XWHanru and I hold interesting positions ourselves in understanding this condition. As Chinese-born curators, we both work in an international context; we absorb information, communicate with different artists, look at exhibitions and participate in discussions with peers and colleagues from multiple cultural and political environments. Such plurality has enabled us to constantly reflect on these issues. Therefore, we are always more interested in the tensions between China and the global situation, the rest of the world, and other different cultural contexts. The point is not to place one in opposition to the other but to examine the complexity of these relationships.

I am very much against the idea, especially for commissioning projects, to have a theme before even knowing what the artists are going to work on; in other words, to let the artworks somehow illustrate a theme—such a method can itself be an act of 'marking territories' through curatorial authority. Therefore, the concrete theme actually came after we did the studio visits, selected the artists, and received their proposals. We understood from the beginning that we would like to work with artists who practice in similar conditions—who understand the plural and rich tensions between China and the rest of the world and share similar concerns.

Therefore, these artists either have experience living and working abroad or have participated in exhibitions substantively outside of the context of China or both. After fully comprehending what they were working on and thinking about, or their interests at the time, the links started to emerge among some of the artists we visited. After further evaluation, we decided to work with these seven artists and artist groups. Then, we provided these artists a set of key words for them to respond to, including ideas of territory, boundary, and borders but we invited them to think as speculatively and poetically as possible. We also provided the same set of key words to the fiction writers who contributed short stories to our catalogue.

What is worth mentioning is that these artworks have all entered the permanent collection at the Guggenheim Museum. The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art Initiative does not only present exhibitions but also builds a collection to contribute to a bigger narrative of our contemporary art history. This is very important and interesting, because another layer of 'deterritorialisation' takes place in this context. We hope that these new commissions will have a different life after this exhibition, after being interpreted in Tales of Our Time; they will go on to be interpreted and displayed in many other exhibitions, in many other narratives, and most importantly, to be connected to artworks produced not in a 'Chinese' context.

The exhibition ends on an uplifting note about the possibility of creating a utopia—another concept of a place—in a contemporary art exhibition.

SBCould you talk about the works that will be shown, and how they reflect the theme at hand?

XWIf I can draw a parallel, I would love to compare this exhibition to a poem, but absolutely not a piece of argumentative writing or expository writing. I hope this can enable an understanding of the relationship between all these artworks with the 'theme' or 'title' of this exhibition, and more importantly, how they relate to each other. As a curator, I never consider artworks as illustrations of a curator's idea.

Curators provide a context for artworks to be experienced but not a didactic speech of how they should be understood. Therefore, for me, making an exhibition is always a process of many threads woven together, from the issues we curators would like to put forward, the ideas the artworks express, and the materiality of the artworks, to the spatial relationships, architectural conditions, the route a visitor will navigate through, how such spatial experience enhances the meaning of an artwork compared to when it is displayed alone, and so on. Perhaps such an approach also differentiates my practice as a curator versus other museum curators.

With that said, I can give a very brief outline of how these artworks connect to each other. But again, these connections are intended to be read as one would read a poem. Kan Xuan takes us to places that used to be cities in different eras of history, spinning from earlier centuries to more recent time, across thousands of years; Chia-En Jao visited sites loaded with historical and political significances with local taxi drivers in Taipei. But it is not only about these specific sites but also Taipei and even Taiwan as a concept of place. Therefore for Kan, it is cities of old times and for Jao, it is the urban metropolis of today. Then Zhou Tao investigates the formation of the urban environment.

Taking Guangzhou and Shenzhen as starting points, he filmed many of the construction sites and their interesting semi-ecologies and the relationship between natural and artificial elements of our contemporary existence. The complex relationship between nature and culture perhaps is also exemplified through Sun Xun's new work, for which he used the mining history of his hometown Fuxin as an entry point. The history of coal mining is itself extremely political and is a history shared by many different regions in the world.

So again, China, or a specific place in China, becomes a connection point for many larger discourses. Then we have Tsang Kin-Wah who looks at the Diaoyu Islands (Senkaku Islands in Japanese), a place that is constantly and enduringly under territorial dispute between China and Japan. He uses this group of uninhabited islands to reflect on the course of history and the relationship between human experience and the writing of history.

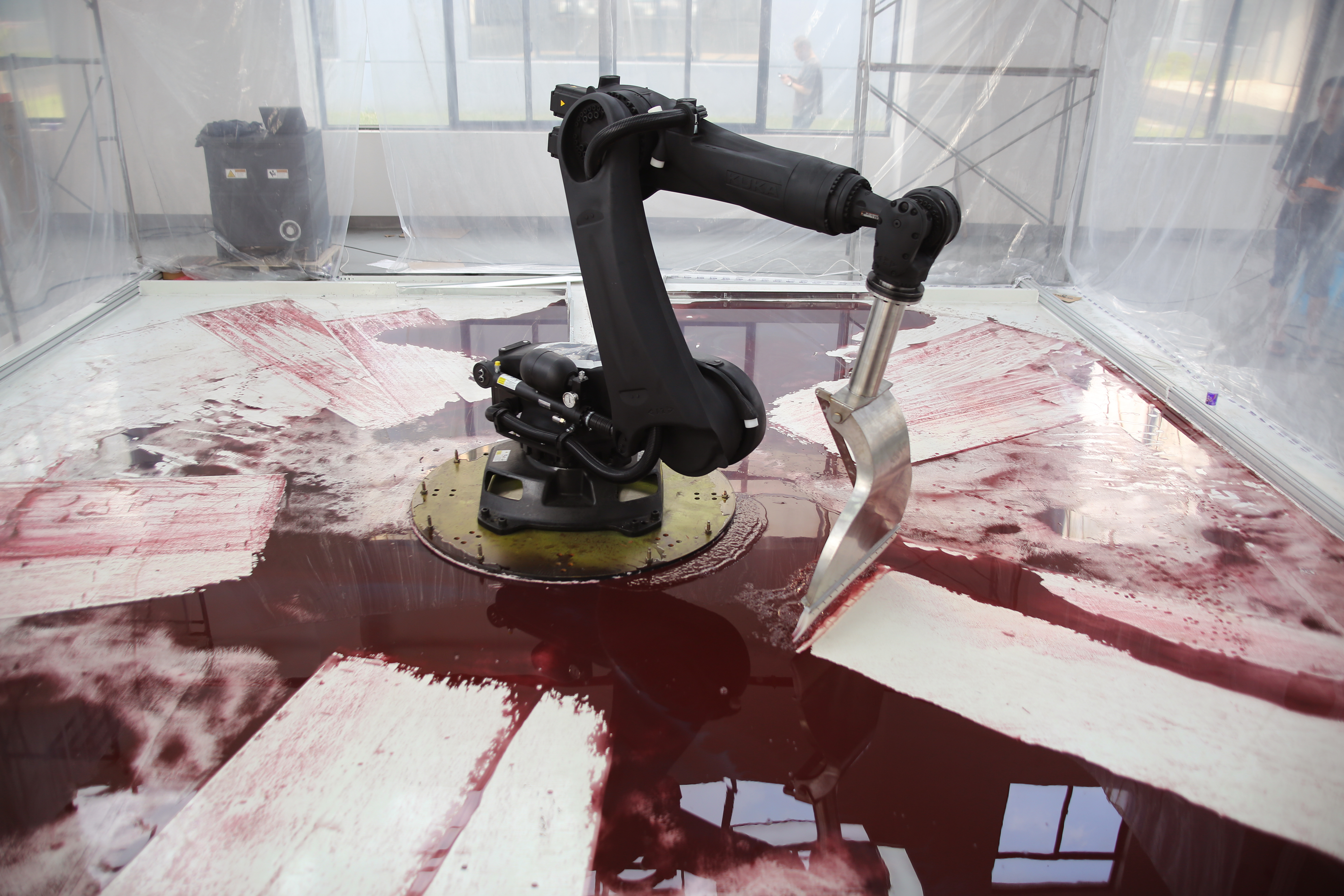

If the above-mentioned artists all consider a specific site as the starting point of their work, Beijing based duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu speak about concept of territory and boundaries in an allegorical way. They have employed a robotic machine and programmed it to conduct a specific action: monitoring a puddle of red liquid on the floor and shovelling it back whenever it spreads over a pre-determined border. But the exhibition ends on an uplifting note about the possibility of creating a utopia—another concept of a place—in a contemporary art exhibition.

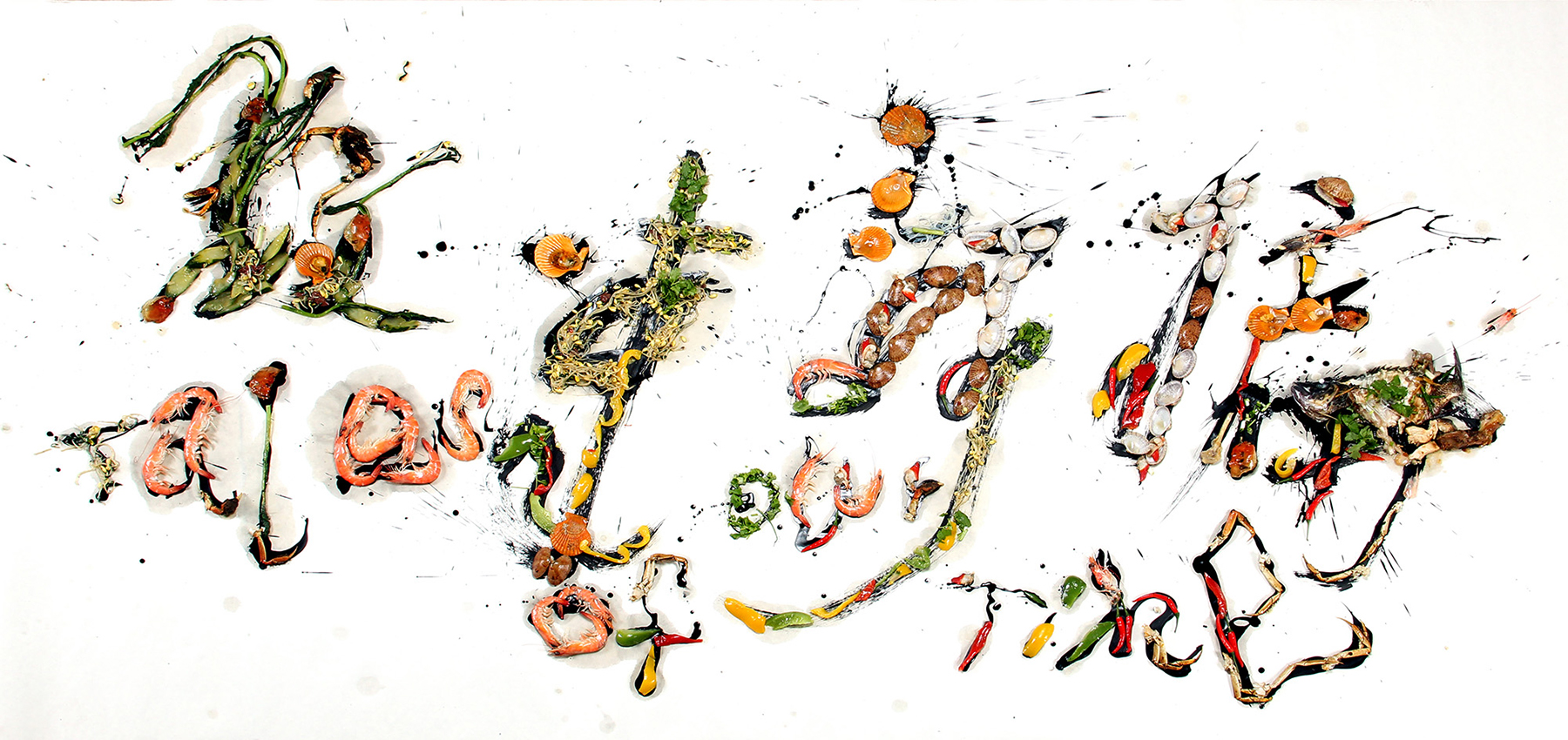

Yangjiang Group transplanted their autonomous zone from Yangjiang China to the Guggenheim Museum. Since 2002, this collective has been organising communal gatherings in their studio, where they invite neighbours and friends to share meals, practice calligraphy, drink tea and play scorer. They have transformed part of the Guggenheim gallery into a tea gathering space, a Chinese garden with calligraphy murals.

SBI am curious about how you made this selection based on the geographical criteria set by The Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art Initiative, which includes what some might call wider China into the mix—that is, artists born in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. There are of course political undertones to this regional framing of China, which makes me think of how Para Site's executive director and curator, Cosmin Costinas, and Asia Art Archive senior researcher Anthony Yung, used the term 'Chinese world' in the 2015 group show, One Hundred Years of Shame — Songs of Resistance and Scenarios for Chinese Nations.

XWTo that end, could you elaborate on the politics of this exhibition, as complex as they are? On one hand, we have a show consciously trying to escape the regional or national frame in monumental, or solid terms—that is, by allowing the definition of 'China' to remain fluid.

If I can draw a parallel, I would love to compare this exhibition to a poem, but absolutely not a piece of argumentative writing or expository writing. I hope this can enable an understanding of the relationship between all these artworks with the 'theme' or 'title' of this exhibition, and more importantly, how they relate to each other.

We are not interested or capable to propose a new 'canon' in how to define 'China', not even the art from China (not to mention China in its historical, political, and cultural complexities) through a small exhibition of such. This is to big of an issue to be addressed through an exhibition, and I am a disbeliever of anyone who claims to do so. But this is the condition we are working from. What you just described is the condition of [The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art] Initiative, on many levels; a parameter we shall be working from. We simply selected the interesting artists whose practices in recent years will make an attractive exhibition and generate previously non-existent artistic connections.

There is not much politics in terms of balancing a relationship between the mainland, Hong Kong or Taiwan in this exhibition. I think this approach has already differentiated us from exhibitions at Para Site, whose exhibitions, in recent years do carry much bigger ambitions. (Para Site is doing very important work and creating interesting narrative-based essay exhibitions.

That's why I have invited Cosmin Costinas to be in conversation with David Harvey, Howard French and Robin Visser as a key part of the surrounding program for Tales of Our Time. They will speak about the intersection of art, urbanism and literature.) We are not escaping/denying/protesting anything but to open and to complicate any pre-fixed frame up. Simply 'escaping' does not equal 'making fluid'. We can apply your same questions to the ideas of what Hong Kong or Taiwan shall be. So what is Taiwan? How do you understand it? Is it just an island? A place whose recent history was made by Chiang Kai-shek? How do people living there feel about Japanese culture? I am afraid the answer is not that black and white. But art practice, through the power of imagination, can make these places and notions plural.

This is not an exhibition based on 'China' but a show with artists participating from the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan. If we continue such rhetoric in interpreting the making of the exhibition and the artists' works from the media world, the art critics, the writers and even the educators, then we will be running in circles and end up in a dead end. We have to think and reflect critically on ourselves as part of the art community and how we actually contribute not so positively and effectively in perpetuating such rhetoric. Have we opened up our own minds? Have we even made an attempt to understand these exhibitions and artworks and artists with fresh eyes? Can we get rid of the burden of pre-existing notions?

One important question I always ask myself: Are there any alternatives for showing contemporary art from China in a non-Chinese context besides the existing models: 1) the historicisation of art, meaning to situate artists in frameworks of politics and identities; 2) the market and commercial success of art and whoever is hot and big? Is it possible to create a different relationship with history? Can we go to the specificities, the specifics of an artist, the specifics of one artwork, the specifics of one element, one object? Are we still able to be imaginative? Can we feel them physically and let go of our mind? Can we love them? Can we balance the sensory and intellectual experience?

The same comments can be applied to the making of an exhibition. It is not just a reportage or commentary of a theme. For me, spatial relationships, site-specificities and all other experiences during one's visit of an exhibition are equally important to what will be read on a wall label.

SBHow does this exhibition fit into the politics of its context—that is, the United States?

XWWhat exactly is the cultural specificity of the US or let's be more specific, New York? How can we understand the idea of cosmopolitan today? Immigration culture? Do the American people know? And how to articulate it? Why is an American audience interested in arts and cultures from Asia, Africa, Latin America? Are people really still interested? Has a kind of global ambition evolved in the past decades? How can American institutions genuinely engage art produced in these places of the world? These are the questions we all reflect on and the answers are not easy. But I would like to consider Tales of Our Time as a trigger for people to think more about these issues, rather than finding ready answers.

SBI wonder if you could talk about how this exhibition develops on your previous work, predicated as it was on creating stimulating moments of cultural exchange? This includes the work you did at the Kadist Art Foundation, and with the Kadist Curatorial Collaboration, which you initiated, as well as the curatorial projects and writing projects you have engaged in prior to your appointment at the Guggenheim.

XWI always think about alternatives to our current condition, alternatives to the dominating art systems, cultural and knowledge productions and circulations, mainstream values and even social organisations: I guess a lot of the things artists think about. I am also a true believer of the power of imagination in art. I think the possibilities of the alternatives come from exchanging ideas and values, which makes the deconstruction of stereotypes possible. I am interested in introducing new things and ideas to people, as I am by nature very curious. I am always open-minded and ready to step out of my comfort zone. I think art is such a great thing when it comes to stimulating people to do the same. Many of our world's problems can be solved by more communication and exchange.

SBIn turn, how do you see your practice developing with [The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art] Initiative at the Guggenheim, and how do you see the Initiative developing as a result of your own evolving practice?

You mention that this is really your first experience within a major institutional setting, and I'm curious how you've experienced the crossover from a more independent, freelance position. You might call this another kind of cultural exchange of sorts ...

XWFor sure. I am experiencing big learning curves, but it's all interesting curatorial experience. I think in the museum context, I am not only an exhibition maker but also a curator in its traditional sense: a caretaker of collections. As I mentioned, these new commissioned works will enter the museum's permanent collection, forming The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Collection together with Wang Jianwei's work, the artist commissioned for the first cycle of the Initiative as organised by Thomas J. Berghuis. I really hope that these works will have a different life, being shown at different exhibitions and museums internationally. At the same time, I am very excited to be able to have a much bigger audience for my work. I am curious to learn how people can create a relationship with this initiative and this exhibition and what kinds of relationship.

But I also miss the independent work environment and spirit. For me, it is really important to always keep that criticality and independent thinking no matter what kind of position I am in. I like to challenge myself. I also would like to create connections between independent practices and institutional practices, not only by myself but also with other practitioners in the field. I want to engage people who are doing amazing work but do not necessarily have a big audience. I think the institution is a great platform to circulate these ideas and knowledge. At the same time, these independent practices also challenge the institution, pushing its boundaries and motivating its reinvention. Perhaps this is how the museum might avoid becoming the 'mausoleum' described by Theodor W. Adorno.

For my upcoming exhibition at the Guggenheim, for example, I am bringing many such independent and critical voices to be part of the programme accompanying the show. I think new innovations in exhibiting and interpreting art from China has to come from such cross-pollinating efforts. —[O]