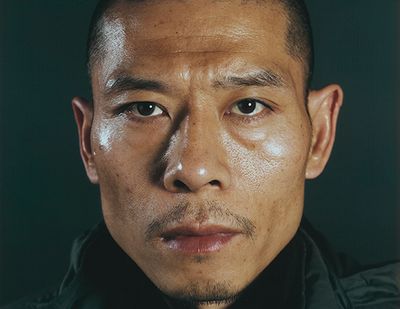

Zhang Huan

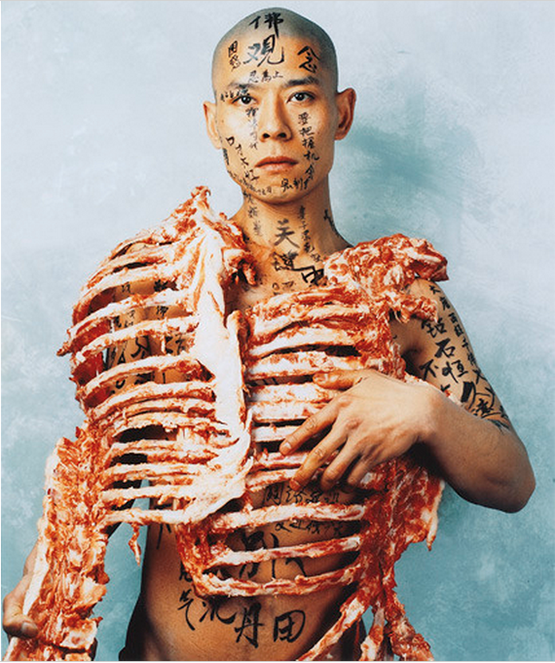

Zhan Huan. © Chuck Close, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Zhan Huan. © Chuck Close, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Few people were all that rich when China finally officially opened its borders in 1978, but Zhang Huan was poorer than most. He was born in Anyang, Henan Province, in 1965, just before Mao initiated the decade-long calamity of the Cultural Revolution. Living hardscrabble with his grandparents in the remote countryside, his early childhood memories are of the deaths of family members and state leaders.

In his mid-20s, Zhang moved to Beijing where he remained poor and itinerant, frequently unable to pay rent, before ultimately settling in the city's East Village. There he created artworks out of barely suppressed screams and his own body: thousands of flies crawled over his skin as he squatted naked in a public toilet covered in fish oil and honey in the performance 12 Square Metres (1994); and his own blood hissed and spat as it dripped onto a sizzling hot plate for 65 Kilograms (1994).

Today, Zhang is one of China's most successful artists, both critically and commercially. In a country where artists accomplish mythic feats—from Cai Guo-Qiang's sky-high daytime fireworks to Ai Weiwei's 100 million sunflower seeds—the artist's ambition still stands out. Works include tumorous golems stitched together from dozens of cow skins, fragments of Buddhist statues made from tonnes of copper and steel, and huge paintings created from ash gathered from incense burners in temples around Shanghai.

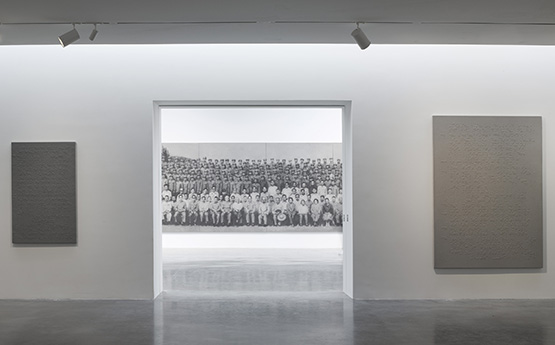

The ash works are a peculiarly literal but genuine attempt to embed spiritual content in Zhang's art. What seems superfluous (what good is the dust after the smoke has diffused and the spiritual communication is complete?) regains poignancy in the details of its use. The ash must be gathered, transported to the studio, sorted by shade and applied, in a process reminiscent of Buddhist sand painting, to the canvas.

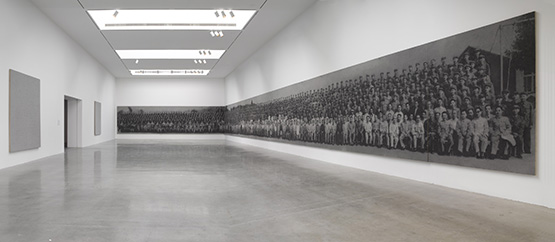

Zhang's ash paintings were included in the artist's solo exhibition, Let There Be Light (30 October–5 December 2015), recently shown at Pace Gallery in New York. In this interview with Shanghai based contributor, Sam Gaskin, he discusses the new forms and meanings for his ash paintings, along with his early life and the broader evolution of his practice.

SGLet There Be Light includes your largest ash painting to date. It's 122 feet long and based on a photograph taken on 15 June 1964, which represents Mao Zedong, the central leaders of his government and 1,000 loyal followers. Scale is an important part of your practice: you've raised the height of entire mountains and lakes, attempted to pull down museums, and super sized yourself with muscle suits made of meat. Is that because you're aware of your smallness in the universe, or in awe of your ability to shape the world around you?

ZHEveryone has his or her own dimensions of life. It is determined by fate. Size and scale don't matter most to my work. What matters is the specific content that an artist wishes to express.

China has a vast national territory. Growing up in such a big country inspires me to create large-scale works that match its expansiveness.

SGThe scale of your work also means you have one of the largest studios and production staffs of any artist in China. Would you introduce your studio and how it's run?

ZHIndividual creation is a campaign by one person, while team creation is the division of labour. The role I play in my team is more like the abbot of a temple or the commander in chief in war. I am the one to develop the principle and route. It is under my control what to do, when to start and where to finish, while my team members do the producing process during the course of the art creation.

We moved to the present studio in 2008. The studio used to be a state-run factory built in the 1970's to produce hydraulic equipment. It is one of the few old factory complexes still remaining in Shanghai, with a total of 30,000 square metres. There are nearly 20 buildings in the studio complex. The main buildings are reinforced concrete structures.

I hope this place is full of energy, suitable for work and living, and also good for artistic creation and a natural environment. The space is quiet and therefore suitable for creation. I really like the 1970's architecture; it's very similar to my experience and background growing up. I also want the workspace to have the energy of life. This is my home; every member of the studio is part of my family.

SGWould you please elaborate on your background and growing up in Henan Province, and the early years in Beijing, and the way it impacted your early work through to the work you do today?

ZHI grew up during the Cultural Revolution and was influenced by the education of the Mao era. After graduation, I gradually began to think in my own way and I changed. Until now, I can sum up my early life by using this word 'uncultivated' (or 'being wild'). I grew up in a village, where life was close to nature, where I could be free and keep my own personality.

I was born in 1965 just prior to the Cultural Revolution in a small town called Anyang, in the Henan Province. Anyang was the capital of the Shang Dynasty and the centre of ancient Yin culture. Seven dynasties had their capital there. I went to live with my grandparents when I was one-year-old. They lived in the real countryside, and when I was there the countryside was very different from what it is now.

The earth was yellow, and everybody wore blue-colored Mao suits. I grew up with my grandmother, uncles, and aunts. Together with other children I cut grass in the field, collected ferments, cleared fallen leaves, and climbed trees. Our main foods were sweet potatoes, corn, carrots, and cabbage. The living conditions were poor.

When I was about 14, I started my artistic training in the so-called SU style or Soviet style. I traveled by bus to an art class after school, and made sketches of bottles and jars. Gu Xijiu was my first art teacher.

I moved to Beijing in 1991 and left the city in 1998 for New York. In those eight years I moved thirteen times, because I either could not afford the rent or I was kicked out. Later I wanted to move to a bigger place. A friend introduced me to an area [in Beijing] I later called the East Village.

I found a place with high ceilings, suitable as a studio, and I rented it for 120 yuan per month. It was there that I created 65 Kilograms, a series of installations entitled The Angel, and other 'poor-artist' works. It was my first studio.

SGFor your exhibition at Pace Gallery in New York, incense ash paintings are the focus of the exhibition. Can you please tell me about how you got started working with this material? Was it difficult to persuade temples to give you their ash?

ZHIn the past, ash from Buddhist temples was scattered into the sea or lakes, dumped in the woods, or simply buried. In the modern society it is processed as garbage. To me, ash delivers the human spirit. At the moment when it is burnt, ash is a witness to the changes and development of a human spirit.

My studio got in touch with the people in charge of the temples, but it was really hard for them to understand my ideas. Usually, I explain patiently to the monks why and how I use the incense ash in my art. The incense goes into reincarnation by becoming a painting material. I often make contributions to these temples to express my sincerity and gratitude.

Every year, we have several cubic metres of incense ash from more than ten temples around the Shanghai region moved to the studio. Generally, incense ash from temples is stored in gasoline barrels and keeps burning in them for about one or two months. When it arrives at the incense workshops they are still burning, and emitting smoke and fire. All day long the ash workshops are filled with smoke. However, many people feel that they can no longer move when they walk there. It's because there is something mysterious in this workshop, something inexplicable and not visible. There is a mental aura.

SGIn the new show you're also exhibiting braille paintings that depict phrases from the Bible and 'The Star Spangled Banner': all in Chinese braille. I'm interested in the production of these braille works, as the technique involved seems quite different from other ash paintings. What is the ash combined with to make sure it retains its form, and how is it applied to the linen to create the convex bumps and concave impressions?

ZHIncense ash is mixed with a bonding agent which is specially made by the studio. The ash is spread on the canvas by hand to make sure of the paintings' quality. This technique took numerous experiments to achieve.

SGAssuming the ash paintings are too fragile to touch, the braille works are an impossible form of communication. They've been compared to religious faith, where empirical examination is at odds with belief. Can you tell us something about the relationship between religion, art and belief in your work?

ZHMy wife and I are faithful Buddhists. Buddhism believes in changes, reincarnation and karma. It expects people to abandon egoism, to attach less importance to themselves, and finally achieve the state of Anatman.

As artists and as individuals, we select materials as message-carriers to reconnect with the spiritual world outside of our everyday life. Incense burning touches and awakens the spiritual impulse embedded deeply in our subconscious. Therefore, the ashes produced already possess a great deal of potential for connecting the human with the spiritual.

The task for me is to solidify these remains of the spiritual life, and allow this evidence somehow to haunt my pictorial depictions of historical events, people or earthly symbols. I select my imagery carefully and hope that, through this haunting process, it will invite a new examination of our collective awareness and experience. And finally, the subjects of my ash paintings shall receive blessings and solicitude from the human world.

SGAre you please able to elaborate on how you select the images for your ash works?Incense ash has extraordinary meaning to me. It was my invention to create ash paintings. To me, ash is not a mere material; it is the collective memory, collective soul and collective blessing.

ZHThere are extensive subjects in my ash paintings. I saw so many impressive images in the old official magazines and the old photos, which reminded me of life I experienced during the past years. The combination of ash and photo images is beautiful; connecting the new world with the past, history with now, belief with real life, collective memory with individual experience. In one ash painting people can perceive a number of elements. The painting can bring unique visual and psychological experience.

The subjects of my recent ash paintings are the Bible in braille, and the US National Anthem in Braille.

SGIn your new braille works, there's also a cultural barrier to communication that the work implies; the messages come from the West (Christianity and US national mythology) but they're conveyed in an Eastern language using Buddhist material. Beyond linguistic and political barriers, are their limitations to what the West and the East can ever understand about each other?

ZHThey convey the conversation, communication and combination of politics, cultures, histories and religions between the East and the West. In the future, more works will break these so-called barriers because art lives in everyone's heart. —[O]