Heri Dono

Born in 1960 in Jakarta, Heri Dono is unquestionably one of Indonesia’s most highly regarded contemporary artists, developing a distinctive style early on that came out of an exploration of Javanese puppet theatre. Drawing on traditional aspects of Indonesian culture and art making, his immersive multi-media installations and paintings speak to the plurality in global contemporary art. Beneath a playful approach through combining storytelling, mythology, machines and animation, there is a poignant socio-political comment on the situation in Indonesia, as well as the fraught interrelationship between the local and the global. Here he talks about his early days at art school, the power of humour and his project for the Indonesian National Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale—only the second time Indonesia has participated.

You studied painting at the Indonesian Institute of the Arts in Yogyakarta in the 1980s before branching out to installation. It was a significant time for contemporary art in Indonesia. Tell me about your early experience.

When I was in Jakarta, where I was born, I saw the exhibition of the New Visual Art Movement in 1975 at the art centre there. In 1984, I started trying to find a formula about the existence of Indonesian modern art because at the time there was no concept of it. We had to follow Paris or New York when talking about modern art, but we had people like Gupta, Tagore and Lao Tzu. I tried to find this formula about tradition and the concept of pluralism. At this time I also created a lot of experimental art, aquarium art, kinetic works and so on.

You were breaking away from what you were taught at art school?

Yes, my work was rejected by my teachers. It wasn’t painting. They thought I was crazy bringing an aquarium in! I treat painting as a language or visual notes. I can make performance, installation or calligraphy through the visual. People who can’t understand language can read it through pictures. In these years, I tried to formulate these ideas and wrote many diaries. It’s not instant though—if you make wine you have to put the good ingredients in and wait for it to ferment. I would look to the language of artists like Miró, Klee and Gauguin in library books. I was at art school until 1987, but never finished. There is no guarantee from an institution to be an artist. It must come from within.

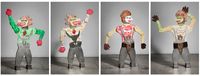

Image: Heri Dono, VOYAGE—Trokomod, Venice Biennale, 2015. Credit Luciano Romano.

In your work you reference many facets of traditional Indonesian culture including glass painting, textile techniques and most importantly, Javanese folk theatre or wayang. You even studied for a year with the master puppeteer Sukasman.

I like to use the shadow puppet performances because I can directly get a message through to the audience. With television, the information cannot be interacted with, just consumed. But today we have computers and we can respond to the information. The shadow puppets at that time, before technology, were very effective in being able to see the reaction of people. Pluralism is the basic idea of the contemporary. It’s about accepting and respecting many different cultures. When Suharto was president, there was only one television channel to control all 27 provinces at that time. Across the different islands there are many different traditions and issues; shadow puppets are a good way to give many perspectives and create solutions. Painting is about the distance between our life and the perspective inside the painting. But with installation, the audience and the artwork are in the same space. It’s the mandala perspective.

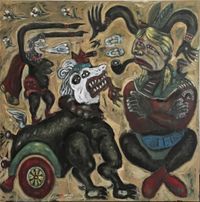

Where did your interest in cartoons, comics and animation come from?

When I was a student I tried to combine animation and animism; they are the same thing with different techniques. In animism, people believe that everything has a soul. When I see paint or pencils, for example, they all have a soul. Life without imagination is fairly dry. I used to love watching fantasy movies when I was a child. When I was nine, Neil Armstrong arrived on the moon but in the story of Flash Gordon they arrived on Mars—further than the moon. I think imagination is more forward than technology. As human beings we can never attain these things—such as flying, but in animism there is life after death. We believe that our ancestors are still around us. When I work I just see my hand moving, I don't think about what I am making.

Image: Heri Dono, works in progress at STPI—Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore. Courtesy of STPI.

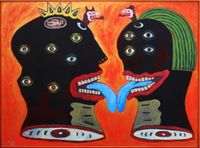

You grew up in Jakarta during a time of intense political turmoil. Behind the elaborate, colourful, fantastical characters and stories at play in your paintings and sculptures, there is a darker social comment present. How do you use humour, irony and parody as tools?

In traditional theatre, the servant or the clown can say anything because they are considered stupid. Artists can act in the same way. Sometimes it might seem that it’s not serious because there is a lot of humour. But humour, like Charlie Chaplin, has a strong concept. It’s not easy to create humour because the people who are creating it must already know the issue or the matter in order to make a parody. You have questioning, discussion, serious consideration of the solutions, and then the last thing is how to laugh. You can either make a protest or a parody. My work is about the humour and the darkness; it’s an oxymoron.

Image: Heri Dono, VOYAGE—Trokomod, Venice Biennale, 2015. Credit Luciano Romano.

You are based in Yogyakarta but travel extensively, having undertaken numerous residencies in Australia, Switzerland, the United States and now the STPI in Singapore. How have these experiences informed your practice?

Residencies are different from exhibitions. During residencies you can communicate with and understand the perspectives of the people from where you’re staying. We can explore art from this message. I have experience as an artist and can share knowledge with people. Exhibition is just a presentation.

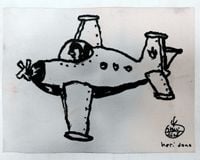

What drew you to the residency at STPI in Singapore?

I wanted to explore hanging prints and to experiment with the medium of paper. There are many facilities here. I try not to use the conventional way to think about print but to question whether it is print or not. I am making prints, 3D sculptures and puppets.

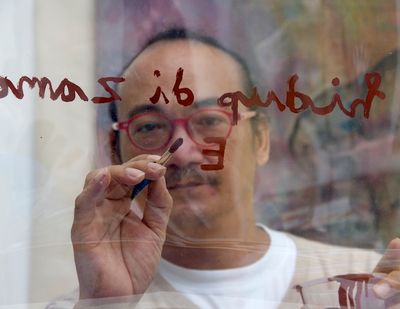

Image: Heri Dono in the artist residency studio at STPI—Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore. Courtesy of STPI.

You are representing Indonesia at the 56th Venice Biennale with a site-specific project VOYAGE—Trokomod in the Arsenale. Would you tell us about it?

It’s about the voyage. I think this time is a very interesting one. Before, in Western countries, when I would discuss East and West it would be a mistake. It wasn’t seen from a geographical perspective. When I saw the exhibition Metropolis in 1990 in Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, they talked about East and West after the fall of the wall in Berlin but from a geopolitical perspective—they considered Latin America, Eastern Europe and North Korea the East. For a long time people didn’t talk about Southeast Asian art—it was a blank spot.

I read in a book called 1421: The Year China Discovered the World by Gavin Menzies about how the Chinese travelled to many countries without conquering or colonising but just introduced things like agricultural machinery and technologies. Why didn’t they colonise these countries? I think it is because of the concept of mandala—that there are no subjects and objects, there is no concept of distance. The Asian concept is like this, but in the West there is Terra Nullius.

My project is about questioning the domination of Western culture or art. The Trokomod is a Trojan horse crossed with a Komodo dragon. The Arsenale in Venice was once used to make weapons, so that’s why I have put the Trokomod there. There is a telescope where people can see artefacts from Western countries, like a judge’s wig, books, weapons or a Morse code machine. The ceiling is covered in Batik with many religious symbols present. There is a periscope to see outside too. —[O]