Richard Bell Calls for a Reckoning

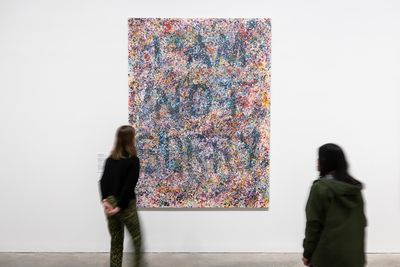

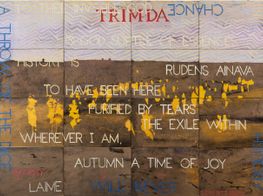

Richard Bell. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photo: Anna Kucera.

Richard Bell. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Photo: Anna Kucera.

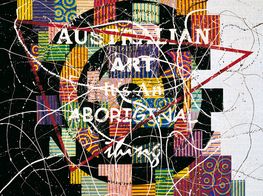

Challenging the discourse of art and art history written by white men, Richard Bell's works are acts of protest in which the rules are rewritten using the same language of oppression.

Born in 1953 in Charleville, Queensland, northeastern Australia, as a member of the Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman, and Goreng Goreng communities, Bell faced the injustices towards Aboriginal people from a young age. Growing up in an Aboriginal community in Queensland, where the government bulldozed his home, the Black Power movement fed throughout Bell's practice, and his life.

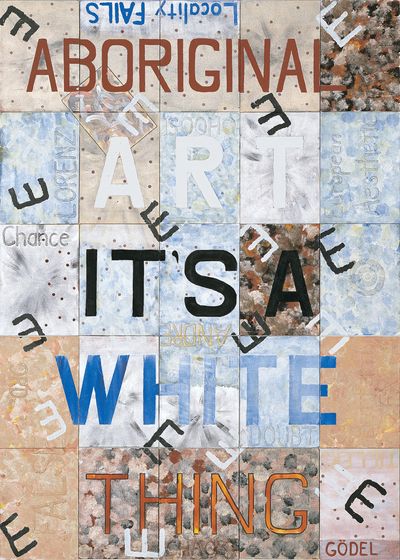

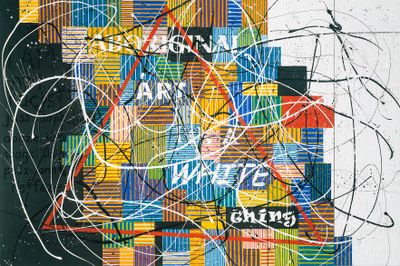

Working for the New South Wales Aboriginal Legal Service in the 1980s, Bell learnt about Aboriginal history, law, public speaking, and bail applications, all of which formed the basis for his art practice. After starting painting at 34, selling souvenir artworks to tourists, Bell developed Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell's Theorem) (2002), which caused waves throughout the Australian art industry.

The painting—and accompanying 'Bell's Theorem' manifesto—dissected the concept of Aboriginal art as a white commodity. Using the text 'Aboriginal Art—It's A White Thing' against a colourful Abstract Expressionism-inspired backdrop, Bell introduced the public to his tongue-in-cheek approach. An art practice that was learnt over 'beers and BBQ'1– in Australia's sunny state, Queensland.

'Aboriginal Art has become a product of the times,' Bell writes in his manifesto. 'A commodity. The result of a concerted and sustained marketing strategy, albeit, one that has been loose and uncoordinated.'2

The artist declares upfront that he is not an academic, and that the manifesto instead reflects his ideology and experience of Aboriginal art. Using Terry Smith's concept of 'The Provincialism Problem' (1974), Bell exposes Australia's cultural cringe, and the replacement of a national art by an othering of Aboriginal art, where spiritual iconography is misappropriated, and rural communities of Aboriginal artists exploited.

He observes, 'Western art is only 500 years old. Aboriginal art is thousands of years old.' Yet, the Western art market sets out to categorise and label artwork from a system that doesn't serve the artist.

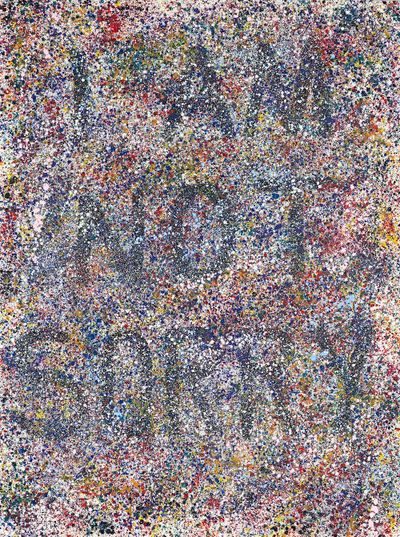

Employing the powerful example of Picasso's appropriation, Bell writes, 'Westerners drooled at Picasso's originality—to copy the African artists while simultaneously ignoring the genius of the Africans'. The same techniques are employed in his own practice, which employs the familiar iconography of Jackson Pollock's all-over painting (appropriated from Native American art) or Roy Lichtenstein's cartoons.

Controversy follows Bell through the art world. In 2003, for example, when he accepted the Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award for Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell's Theorem), Bell wore a T-shirt reading 'White Girls Can't Hump'. And again, in April 2011, when the artist revealed he had selected the winner of the Sir John Sulman Prize through the toss of a coin.

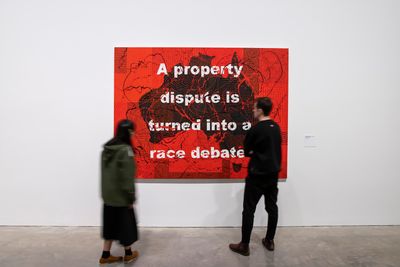

Bell's artworks, like the artist himself, do not hide behind a veil; they are upfront and blazingly direct in concept. Titles like Pay the Rent (2009), and placards reading 'White invaders, You Are living on Stolen Land' use language all audiences will understand, and, hopefully, lead to critical discussion and feelings of discomfort in the white settlers who benefit from this power system.

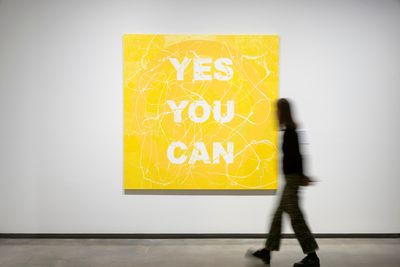

Bell's new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), Sydney, You Can Go Now (4 June–29 August 2021), curated by Clothilde Bullen, is his largest yet, pulling together works from his 30-year career. The title, which cheekily co-opts his own phrase, is open to interpretation. It sets the scene for black empowerment and that white guilt Bell enjoys generating.

You Can Go Now includes every video artwork Bell has produced, including the satirical Scratch an Aussie (2008), a collaboration with Aboriginal historian, activist, and long-time friend Gary Foley, where Bell plays a 'Freudian' therapist as they explore the racist, harmful beliefs that prevail today.

Collaboration is a theme that runs through Bell's practice—from those early beer and BBQ art lessons to founding the proppaNOW collective in 2003 with fellow artists Vernon Ah Kee, Tony Albert, Megan Cope, Jennifer Herd, Gordon Hookey, and Laurie Nilsen.

His installation Embassy (2013–ongoing)—a recreation of the original Aboriginal Tent Embassy, the protest camp set up on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra in 1972—embodies this collaborative approach. The tent is back at the MCA Forecourt with talks, workshops, performances, and film screenings. After, the work will travel to Tate Modern's Turbine Hall in 2022.

In Bell's practice, art becomes a way to expose his anger and frustrations around Australian political systems. In this conversation, Bell speaks with art writer Emma-Kate Wilson about the methodology that allows him to say what he's really thinking.

EKWYou Can Go Now at MCA Australia is your largest solo exhibition in your 30-year career. Looking back on your practice, how have you seen things develop or change?

RBI'm experimenting all the time. I do see changes in focus and direction. I'm very happy with how my painting career has gone.

My art has always been quite direct. That reflects me as a person as well. There's an authenticity. What you see is what you get.

EKWDuring those 30 years, your work has been very political; activism runs throughout. Do you find that you are still talking about the same issues, or has that changed in time?

RBOf course I'm talking about the same things; I'm talking about colonisation here. And the resolutions to our problems are not overnight fixes. They are things that have to be worked on for long periods of time, and generations, in fact.

I have no sense of urgency with our movement, and I don't think we've moved very far. But then, I think that's a result of global circumstances leaning towards fascism around the world. That hasn't missed us here. These are not ideal times for us; instead, we should be trying to develop strategies and take stock of where we're at.

EKWArt can both comment on the politics of the time, and start to influence decisions and people's perceptions. Is that something you've found?

RBI believe that, yes. Why else would I do it?

EKWYou've been around the world sharing this message as well. Have you found people are surprised about the treatment of Aboriginal people in Australia?

RBPeople are pretty familiar with colonisation—it's a pretty popular practice among Europeans in the last couple hundred years. They already knew. When I was in America, they recognised their own circumstances with Native Americans.

EKWYour work taps into familiar iconographies in 1960s Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, by artists such as Roy Lichtenstein and Jackson Pollock. When did you first realise you wanted to pursue this style?

RBI wanted to do it in the 90s but didn't get around to it. I didn't get to paint these things at all until the early 2000s. In 2002, I made a work for the Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, and I knew that the market would want more of that kind of work, so I started doing the Lichtenstein works instead. It was my next show, which opened a week after I won the Telstra Awards.

People always ask, what are you doing next? But I had already done it. After that, I didn't make any more of those kinds of works for a couple of years.

EKWThat work that won the award, Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell's Theorem), explored the role of Aboriginal art in the Western art market, which is often rife with theft and exploitation. You created the work in 2002; has anything changed since then?

RBIt's still pretty much the same. From the outside, it doesn't seem to change that much. It doesn't seem like much has changed.

EKWDid winning change your career?

RBNot really. I'd set myself on a path that was fortunate enough to include winning that prize. I'd already mapped out where I was and what I wanted to do. I wasn't going to make any more works like that for a couple of years. I just experimented with painting, and painting styles, and approaches.

EKWCan you give us a little bit of background about that work and when you started developing the manifesto?

RBI'd had a break from making and exhibiting work. I had a young family and spent time with them for about seven years or so. I didn't make a lot of work, to be honest. And then I came back and had discussions with friends.

Rather than changing the politicians, we need to actually change the system of government that we have. We need a reset.

One of the things that came out of discussions with [fellow artist] Vernon Ah Kee, is that you need to be making work that engages in the discourses around art. Much of the discourse and discussions about contemporary art were by white men. And I didn't find anything interesting there, at all. So I decided to write my own.

I wrote the manifesto in the latter part of 2002. The urgency to make it came from the fact that I was set to have a solo show, but the art gallery at the time didn't have faith that the works would sell. And I'd already made the goddamn works.

The gallery turned my solo show into a group show that included works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Michael Nelson Jagamara, and Imants Tillers. So I wrote a rationalisation for having a show with one of the most famous appropriators of Aboriginal art in this century.

EKWYou mentioned discussing your work with Vernon Ah Kee, with whom you launched the proppaNOW artist collective alongside Jennifer Herd in 2003. How important is it to have connections with other artists?

RBFor me, it's really important. I always had important discussions with Gordon Hockey, Jennifer Herd, and Laurie Nilsen. We got to spend time with people and talk about a lot of things, and that really helped me.

EKWBrisbane has been a real hub for that; are you seeing collectives re-emerging with the next generation?

RBI'm not sure. I haven't seen much, to be honest, but I'm a strong supporter of collectivisation. In this corporate world, we need that.

EKWSpeaking of collaborative approaches, I was excited to see Embassy at the MCA Forecourt. What can we expect from the talks, workshops, performances, and film screenings planned?

RBI'm going to have discussions with some of my friends and other interesting people. For this Embassy, I want to try and take advantage of as many local guests as possible.

It's very difficult to actually direct money towards artists. We still only get about five percent of the entire arts budget. We make the product, and we get five percent. A lot of the people in conversation are artists or have been artists. I let them in to talk about what interests them. People seem to like it.

EKWAnd then the work is travelling to Tate Modern's Turbine Hall in 2022.

RBYeah, next year. Fingers crossed. We don't know what the government's going to be saying; they let their rich friends out. People are leaving the country and coming back. I don't understand that, but there's a possibility that there'll be no travel out of Australia for the rest of us until 2023. I'm just hoping that they can get their shit together and roll out the vaccines, better than they have done anyway.

EKWHas Covid affected your practice?

RBIt's driven me to make more work!

EKWSo, you've been quite busy?

RBI've been very busy. I've been lucky to live in Brisbane; we've only had one or two months in lockdown. We've had quite a bit of freedom.

In this time, I've been able to work in my studio. I can have two or three other people in there; there's so much space. It's been a very interesting time. There's been lots of content. Workwise it's been good for me.

EKWWhat sort of themes have you touched on in the artworks you've made this last year?

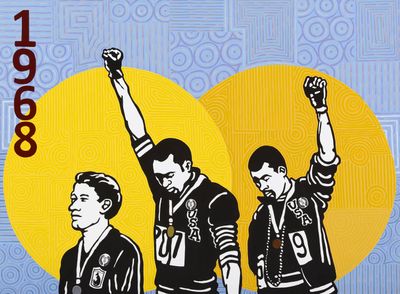

RBBlack Lives Matter, of course. That was the first thing to take Covid off the front pages of the newspapers—the lead story on television and the internet. It was incredible, how they organised and stayed safe. It was a phenomenal story. I think that's my biggest takeaway from 2020.

EKWAnd what did you think of Australia's response to Black Lives Matter?

RBI thought the young kids who protested and the adults that supported them were magnificent. They made a decision. I know I did. I had to make a decision about whether I would go or not. And I came to the decision that police brutality trumps the pandemic.

I'm glad I went, and there were a lot of other people who went. It looked like it would be an illegal march, and the government was very strong on that. But then we just said no, we're doing it. We have the right to do this. And I got there with Sarah, my daughter, and there were police everywhere, but they were handing out masks. They defused any violence. It turned out really well.

EKWIt really was a questioning time for Australia, hearing the comments from Scott Morrison, and his complete denial that Australia has a problem with race and its colonial history.

RBHe went on holiday during the bushfire crisis. He's shown his inactivity, and in response to BLM, the reaction was expected. Knowing that, I thought that it was really courageous for people to make that decision and attend those marches—and to be safe. Otherwise, if they'd generated any kind of covid crisis, it would have been all over the media.

EKWI was moved seeing artists' responses as well. I thought it was creative and broke down complex and challenging issues for people to understand.

RBI think the youngsters and people organising these marches and carrying them out did their job, and the artists did their job. I'm pretty happy in those two regards. Last year changed the world, and we are still seeing the results.

There's a whole lot of conditioning happening as we speak, and more around the country. I challenge some of that conditioning and offer alternatives. Challenging some of the things that are presented as fact. A lot of it is fake news.

EKWWas the MCA exhibition planned prior to 2020, or did it come together in the last year?

RBIt was planned before. It was actually due to be last year.

EKWHas that extra time helped you put together more work or more ideas?

RBNo [laughs]. I don't think any of the new works made it into the show.

EKWI was curious about the title as well; I know these are always tongue-in-cheek. How did you land on that phrase, 'You can go now'?

RBI borrowed a saying from Paul Newman, years and years ago. He was playing the part of this famous Southern politician in America, and one of his lines was, 'That's a lie. That's a lie. That's a goddam lie.' I said that, but then people started repeating it to me, and I thought, I'm going to have to get my own saying.

When somebody announces that they are going and as they start to get away, I'll call their name, and they'll turn around, and I'll say, 'You can go now.'

EKWDo you have any visions as to how the public or the media might read into that?

RBNo. I'm prepared to wait. That's not my problem [laughs]. My job was to make the work and give a title to the work that challenges the legality and the legitimacy of the colonial government that we have here.

I believe that this land always was, and always will be Aboriginal land. Now, if people don't like that, well, there's an invitation in that title.

EKWHow's the relationship been with the MCA and the exhibition's curator, Clothilde Bullen?

RBI've known Clothilde for a long time. I know she wanted to tell her story through my art. She has her job; I have mine. But she asked me to name the show. There's always a negotiation in these matters. There's a hell a lot of work left out as well.

EKWI wanted to discuss your relationship between your art and activism. Do you ever comment on that?

RBI still see myself as an activist, but I don't have any organisational role. I've never spoken at a rally or protest. I think there are other people who are much better at that than I am. I've always been quite happy to defer to those people. I describe myself as an activist who masquerades as an artist.

Admittedly there is a lot less activism these days. That's for young people—they get out on the streets and challenge. I join them as often as I can.

EKWActivism can take so many different forms. And I think having art that continues to be shown in major galleries and across the world is in itself a huge point of activism.

RBMy art has always been quite direct. That reflects me as a person as well. There's an authenticity. What you see is what you get.

EKWI've always appreciated that about your work.

RBOther people have a different take on it. The world's made up of all different kinds of people.

EKWIt's good to have a blend out there. There are works that have hidden symbolism, but then I do think a lot of people need things that are blunt and in their face.

RBThere are enough people out there making subtle works.

EKWI didn't grow up in Australia, so learning about your works was a bit of a lesson for me—it sent me on a tangent. I did really appreciate that the works didn't leave me having to figure anything out. I felt like the message was right there. Some audiences need that.

RBThere's a whole lot of conditioning happening as we speak, and more around the country. I challenge some of that conditioning and offer alternatives. Challenging some of the things that are presented as fact. A lot of it is fake news.

We, the Aboriginal people, in order to seek justice, are referred to as a structure, which is built and peopled by the coloniser. How the fuck can there be any justice in that kind of conflict resolution?

EKWIt's so true. I think, especially with activism and activists now, the larger system has to change, because the current politicians aren't going to—that's not in their interest at all.

RBThe way politicians have behaved, it's bordering on treason to wilfully take us down this path of continued carbon-based fuels, with no money whatsoever for renewable energy. That is actually treason, I believe; that is a treasonous act. There needs to be a reckoning.

Rather than changing the politicians, we need to actually change the system of government that we have. We need a reset. One of the projects I'm working on at the moment is a draft constitution for a new republic. We take some of these decisions that the government and some of these politicians are making, take them out of their hands, put them back into the hands of the people.

There's a question about renewables or carbon, for example. Let the people vote. Let there be discussions about it and make sure that people are well informed.

EKWThey are happy to do that when it serves them.

RBWe have a Prime Minister who actually brought a lump of coal into Parliament House, like what the fuck was that.

EKWYeah, it is shocking.

RBIt's probably the worst piece of performance art in Australian history!

EKWYes, I love that. Critique his art! Thanks so much for the insight.

RBThanks for taking the time. And as they say, you can go now. —[O]

1 'Richard Bell: "My art is an act of protest", interview for Tate, Accessed 3 June 2021, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/activist-art/richard-bell-my-art-act-protest

2 Richard Bell, 'Aboriginal Art – It's a white thing!', Accessed 3 June 2021, http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/great/art/bell.html