Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Past, Present, and Future

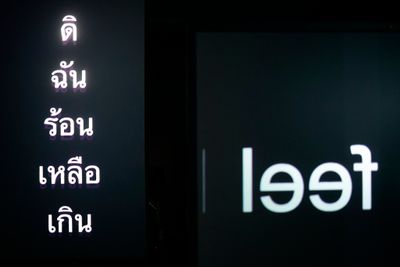

Apichatpong Weerasethakul. © 100 Tonson Foundation, 2021. Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul. © 100 Tonson Foundation, 2021. Photo: Supatra Srithongkum and Sutiwat Kumpai.

A recipient of the Palme d'Or in 2010 for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, Apichatpong Weerasethakul won his second Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in July 2021 for Memoria.

Weerasethakul's first English language feature film, starring Academy Award-winning actress Tilda Swinton, will go on release in the United States from 26 December 2021, where it is intended to be shown in one cinema and one city at a time.

Before then, the second chapter of Weerasethakul's two-part survey exhibition A Minor History will open at 100 Tonson Foundation in Bangkok on 25 November (Part One: 19 August–14 November 2021; Part Two: 25 November 2021–27 February 2022), making this an ideal time to talk to the artist about his practice so far.

An internationally acclaimed film director, Weerasethakul recalls the multifaceted talents of other prominent directors like David Lynch, Wim Wenders, or Gus Van Sant, regularly exhibiting with renowned museums, institutions, and art galleries as a visual artist. __

A Minor History is a homecoming of sorts for the filmmaker, tracking his return to Thailand after shooting Memoria in Colombia in 2019. The first instalment of the show is a cinematic portrayal of Isan, Thailand's northeastern region where the artist grew up. Photographs show views of the Mekong River hung upside down, as if to stress a collapse of the natural ecosystem. A call—if not a scream—for help.

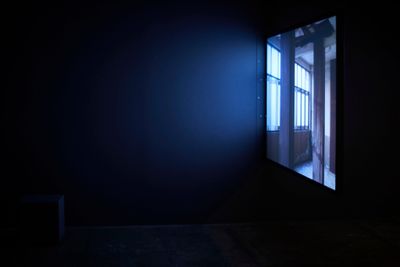

An emphasis on architecture, which bears a connection with the artist's origins as an architecture student, heralds one of the main themes of the three-channel video installation, A Minor History (2021): the skeletons of abandoned buildings and the stories they hold.

Three sets of double-sided screens are positioned against the backdrop of an Isan folk performance pasted across the gallery's back wall, giving the impression of a shrine, showing daylight and nighttime scenes along the Mekong, including a view of a deserted theatre set, and scrolling text.

The voiceover of Mek Krung Fah, a young poet from Isan, performs the male and female voices of a couple in dialogue about mutilated corpses discovered along the Mekong River, recalling the fate of anti-government protestor Surachai Sae Dan, and the death of the naga—a mythical serpentine creature that is popular in Isan.

For Weerasethakul, A Minor History is a tribute to bygone forms of expression that have inspired him—environmental, architectural, visual, textual, and sonic, among others—that he considers 'remnants'. This accumulation extends to the interviews and photographs he has taken for the project, which enabled him to reflect on Thailand's shifting political climate.

A Minor History shares a formal commonality with Memoria, in that both fluidly move between the realms of art and film. Throughout the artist's work, images and soundtracks are designed to trigger memories and emotions, unleashing the synaesthetic potentialities of audiovisual composition.

Exemplary of this emphasis on cinema as a sensory experience, are the artistic experiments that Weerasethakul has designed at the periphery of cinema. Fever Room, first organised in September 2015 at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea, was his first projection performance piece, for which Weerasethakul took his cinematic weaving of dreams and history to the origins of theatrical imagination: the cave.

For Sleepcinemahotel, a pop-up guesthouse in Rotterdam in 2018 as part of the International Film Festival Rotterdam (24 January–4 February 2018), guests could fall asleep for a night surrounded by underwater views, marine scenes, archival imagery, among other materials, projected on circular porthole-like screens.

Such a rich and diverse body of work—with recent institutional presentations including Periphery of the Night at the Institut d'art contemporain in Villeurbanne (2 July–28 November 2021)—makes Weerasethakul one of the most widely exhibited filmmaker-artists in the world. It also epitomises his idiosyncratic versatility to knit his art in and out of the realm of cinema.

That versatility infuses A Minor History. With the second instalment of the show scheduled, the artist had yet to decide what he will show at the time of our discussion: an uncertainty that mirrored the current situation of his country in real-time.

We spoke as the opening for his exhibition at 100 Tonson Foundation in Bangkok was postponed by the capital's strict Covid-19 lockdown. That brief pause offered an opportunity to talk to Thailand's most famous international movie director about his past, present, and future.

RJLet's start with your past, and in particular your family background. With Thailand being a multi-ethnic country, what do you know about your roots?

AWMy grandfathers from both sides came from South China. When they came to Thailand, they had wives here too. Polygamy was a socially accepted practice in Thailand until the adoption of a law on monogamy in 1935.

RJDo you know where they came from in China exactly?

AWNo idea. My dad used to speak Chinese, but he died a long time ago. I want to visit, but I haven't had the chance to. My father was from Nakhon Sawan, which is 250 kilometres north of Bangkok, and my mom is from Bangkok.

The way I create these artworks is really spontaneous, as is the case with the installations. It's always shifting.

RJCould you tell me a bit about your religious background, too?

AWI was raised in a typical Buddhist family. But in Thailand, religion is mixed with animism and Hinduism in a kind of ritual-based Buddhism.

My family was not so strict in terms of religion, because I grew up in a medical household. Both my parents were physicians and worked in a hospital in Khon Kaen in Isan province. But my parents, like other families, still went to temples to thumboon (ทำบุญ), or make merit, which consists of making offerings to the temple and the community of monks in order to accumulate good deeds for the future.

RJWould you still consider yourself as a Buddhist?

AWNot now. But my upbringing has influenced some of my ideas.

RJYou left to study filmmaking at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1990s. What was the artistic scene like at the time? Did the legacies of Dada, Fluxus, or John Cage have any influence on you?

AWDada was pretty influential on me, as well as the Surrealist movement, but not John Cage. I read about him later on. I was more into movies.

Filmmaking was what I intended to learn there. But I was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which is integrated into a huge museum in Chicago. This institution has all kinds of collections, including Classic, Impressionist, as well as Surrealist works, so you could see abstract works alongside those by the Surrealists, including Buñuel and Dalí, and then at the same time to see Iranian and Taiwanese cinema. Somehow they coexisted.

I was really interested in Joseph Cornell's 'boxes'. His work has opened my mind, in particular his approach to chance and humour. Another influential experience was seeing his short 16mm film The End is the Beginning (1955).

RJCould you tell us a bit more about the influence of the Dada movement on your work? Did you look at Dada movies?

AWYes, I did. It was the way that they used sound in their movies that interested me. Maya Deren, for example, was influenced by rituals, voodoo, and Surrealism, and the soundtrack of her short movie Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) was composed by Japanese artist Teiji Ito.

RJSpeaking of voodoo, was I Walk with a Zombie (1943) by Jacques Tourneur a movie that you encountered at that time?

AWI saw it later in France, actually, when I had already made films. I was in my thirties or forties.

RJCan you explain your choice to take the name of Tourneur's main character for the role embodied by Tilda Swinton in Memoria, your latest movie? Was it intentional?

AWYes, it was. I was really struck by that film, and in particular the character of Jessica Holland—a Caucasian woman and the wife of a sugar plantation owner in the film. Although slavery was abolished at the time of the story, the scars of colonisation and slavery were still very present.

Jessica suffers from a serious illness. In one scene in the film, she is lying comatose in bed before being caught by the sound of drums at night. The ritual aspect of the drums struck me, as well as the elegance of her simple walk that follows.

When I was shooting Memoria, I was thinking about this particular walk. And the whole movie has a lot of walks as a gesture to trace this memory.

RJWould you say that this movie has aged well? Especially in light of the Black Lives Matter movement.

AWOh, I see what you mean. Personally, yes, but I think that's the point of filmmaking. It's a testament of people's ideas and even prejudices at that time. In terms of movies, I don't see the point of erasing that, or try to blame it.

RJBeside filmmaking, you also make photographs, installations, and videos. How do you define yourself as an artist?

AWThat's tricky. I call myself a filmmaker slash artist.

RJWhat about your cultural identity? Isan, your native region in the Northeast of Thailand, has been very present in your movies, including through the use the local language. Would that make your work more Isan than Thai?

AWI can't say, because problems always come up when you try and label something, especially for the locals or a nation. I would say it's just me!

To me, language is an illusion. When you see Memoria, which is shot in both English and Spanish, it's part of the soundtrack. So, it's like music, but it doesn't tie the movie down to anywhere or anything. It's just an illusion that you think that it's a Thai movie. It's just a movie.

RJSo is your work hybrid?

AWOh, for sure. And that's because cinema itself is hybrid.

RJYou also refer to the organic nature of your work.

AWOrganic, yes. I think it's more expressed in the short films or in the art videos. That's the way it grows. The way I create these artworks is really spontaneous, as is the case with the installations. It's always shifting.

RJWould you ever go beyond vision and sound in your installations, to include the sense of smell, for instance?

AWFor me, it's still based on visuals. It's more about the mental trip, which is mainly visual and sonic.

RJBesides visual arts, what's your relationship with other art forms?

AWI am particularly interested in Japanese literature. I was infatuated with Yukio Mishima, for example. I also like his contemporaries Yasunari Kawabata and Jun'ichirō Tanizaki.

Tanizaki and Mishima are quite important for me, in the way that they express hidden desires. And the way Tanizaki expresses himself through architecture, especially in his very beautiful work In Praise of Shadows (1933), where he talks about the poetics of Japanese architecture.

RJThat relates back to your initial training in architecture before your studies in the U.S.

AWRight.

RJWhat about Thai literature? Writer and curator David Teh places your work in the genealogy of nirat, a Thai verse form characterised by themes such as itinerancy and homesickness.

AWI've never read nirat, but I know the concept of it. Nirat is really tied to the official narratives and the royals. So obviously, I'm not interested.

RJFor David Teh, nirat aesthetics appear through your particular interest in mobility, displacement, and longing.

AWOh, then there could be a connection.

RJLet's shift to the present. We are here at the 100 Tonson Foundation, where A Minor History, your new exhibition, has just started. Can you tell us about it, including your emphasis on sound?

AWI was interested in the relationship between sound and image, and how it can trigger memory, especially traumatic memory. I have exploding head syndrome, and when I was working in Colombia with this sound in my head, I was simultaneously exposed to stories about how people approach violence in their daily lives and how they remember sound from those experiences.

Certain sounds can trigger memories. In this film, I wanted to trigger the audience's memory, and also my own memory. In Memoria, it's not only about the character in the film, played by Tilda—it's more about an internal or hidden memory in all of us that's vibrating but that we don't hear or register.

In the movie, she's tapped into that. In the end, it's not really about her, it's about us. It's about collective experience.

RJMemoria is not only the title of your last feature film, but also the title of a previous exhibition at SCAI The Bathhouse, Tokyo, in 2017.

AWYes. I was developing the script at the same time as the show in Japan. It's not really tied to the movie. Here in Bangkok, it's after Memoria, back to Thailand, and starts to travel in the realm of local violence in Thailand.

RJA Minor History is composed of two chapters, with Part Two opening on 25 November 2021. How will they differ?

AWI don't know yet, because I'm always changing. Part One is about the remains of dead animals. It is also like a place or a landscape, or a memory, that ties in with sound.

It's about this mixture of impressions—the travel in Isan with cases of political prisoners and murder. And also old cinema, with old-school film dubbing, and there's only one man who impersonates different characters who are male and female, and then there's also the use of mor lam (หมอลำ), a traditional form of song. There are hints of all these bygone expressions.

RJYour reference to remnants seems very close to 'hauntology'—a concept coined by French philosopher Jacques Derrida.

Referring to the return of elements from the past, as in the manner of a ghost, the concept of hauntology was later applied to your work by scholars Ronald Rose-Antoinette, Toni Pape, and Érik Bordeleau, and Adam Szymanski in Nocturnal Fabulations: Ecology, Vitality and Opacity in the Cinema of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (2017). Would you endorse such a connection?

AWThere can be a connection. Here, it's more like a re-creation of these remnants.

RJWhat do you want to state through this show here in Bangkok at this particular time?

AWIt's a tribute. For the first part of the show, maybe it's a farewell to those remnants that I've witnessed—the remnants of nature, architecture, and modes of expression. So, there's a kind of appropriation of different styles of storytelling and text.

There's also an observation of the changes in the Mekong River. I've recorded it in films and photography for more than ten years. I went there because of the fluctuation of the water level due to the construction of the dam in China. It's been ongoing, but this year in particular, you start to see the collapse of the ecosystem. The water is changing colour from brown to green-blue, which is not Mekong!

Even Marguerite Duras wrote about this muddy colour in The Lover (1984), but now it's gone. I document this change of colour and tie it to the corpses floating along the river—the recent ones, but also the many corpses from the past floating down.

I tie the idea of bodies into this show—the divine body, the mutilated bodies of activists, and the body of belief. All these things that are disintegrating in my memory, in reality, and for sure in Isan.

There's also the collapse of a belief system. The mythological serpent creature naga is such a big symbol of hope in the northeast. But in this work, I propose the death of naga. It's quite extreme. But it's done with the approach to entertainment that I grew up with, because when something bad happens in this country, there's always a cover with entertainment.

There's a soap opera right after the news or a radio drama and all this sugary media. When I was young, when the 6 October event happened in 1976, there were nonstop cartoons on TV, when people were being killed in Bangkok. The cover with entertainment here is very strong. So this film is the same.

In the film, there is this romance between a man and a woman who walk along the river and talk about these corpses and the naga dying. So, there's this element of play. Even now, we don't know where the corpse is of one of the political activists who disappeared around 2019. Two corpses have been found, but one is still missing.

In the making of A Minor History, I spoke to a guy from an emergency rescue service foundation in Mukdahan. Salvaging bodies from the river, he talked about one corpse in particular, which he couldn't bring into the village because it's considered bad luck. So he had to carry the corpse over kilometres, along the river.

I tie the idea of bodies into this show—the divine body, the mutilated bodies of activists, and the body of belief. All these things that are disintegrating in my memory, in reality, and for sure in Isan. By the next chapter, I hope it will be talking about a new spirit that is born from these corpses.

RJSo, this Minor History is multi-layered with themes related to spirituality, activism, ecology.

AWYes, there are many things, but it's very minimal.

RJRegarding the abandoned cinema that is featured in your video installation, is it also a call for greater protection of cultural heritage in Thailand?

AWYes, but of course I'm not campaigning to bring it back. It's just how I experienced movies growing up. So, there are some romantic and nostalgic ties to that. And now there's a lot of streaming that I think is threatening the life of cinema and theatres in the future.

RJPro-democracy solidarity movements have hit the headlines over the last year, including online movements such as the Milk Tea Alliance—made up of netizens from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand, and Myanmar. On the ground, pro-democracy protestors have co-opted a salute from The Hunger Games trilogy. How do you perceive this intertwining of fiction and reality?

AWI think it is always going on in our lives. In this show, it's about the naga, and how people appropriate it for their beliefs and for their cause. In Nakhon Phanom and Ubon Ratchathani, which are in the northeast, there's a huge culture around the naga. There, images of the naga are appropriated and commodified for Instagram.

I always approach my work with joy and pleasure. I think that making a Hollywood blockbuster would be very stressful.

The younger generation are doing the same thing with The Hunger Games, in this almost mythical dream of dealing with the regime. They've adapted it to their cause, to justify their existence or their ideology.

I think that's what makes this movement very appealing to me, because it's not my logic, this appropriation. It also collapses the status quo of the social ladder in Thailand and in Asia in general. The strength of the belief system is really weakening.

I found it addictive to observe these kids challenging and eroding the old system, almost anticipating the collapse of this huge mountain or animal. I put this in the voice-over in Cemetery of Splendor, which I made in 2015. It was about this anticipation of a collapse, and I think it's happening.

RJLet's move forward and look to the future. You have recently spoken about your plan to make documentary films. Could you share more about what you have in mind?

AWThe inspiration to call the show A Minor History is because our major history is full of official tales, especially from the palace and important people. So, I see the need to document everything.

For example, the way the education and schools work in Thailand is really unique, and for me, dangerous. The same applies to the healthcare system. When you go to the big Khon Kaen Hospital, it's like a war zone. People scramble for healthcare. Even though healthcare is free, thousands of people wait in line from three in the morning.

These realities fascinate me, and I think it's urgent to document them. Even now, we still have a lot of propaganda. The money spent by the state is all about image-making, which glorifies the system. That's the opposite of what we should be doing.

RJDo you have a favourite documentary filmmaker?

AWI really admire the documentaries of Frederick Wiseman. He lives in France, but he's from the States. He has a 'fly on the wall' approach to observing.

RJWhat about the documentaries of Ai Weiwei?

AWYou know what? I'm not really familiar with his work.

RJMichael Moore? You have a Palme d'Or in common...

AWI think Michael Moore is almost like an investigative journalist. For me, it's about observing the system. It's a different approach.

RJYour work is very much about immersive experience. What are your views on virtual reality?

AWIt's funny that you ask, because I'm developing a new VR slash AR with Japanese and Korean collaborators. But it's so new to me. I still haven't tried the headset, which is waiting for me in Chiang Mai.

I believe that VR is the way to go, because it's so close to the way we experience dreams. I think there's a relation between cinema and dreams, and the way cinema evolves, from silent to sound, black and white to colour. But in dreams, there's no frame!

I think VR is trying to solve that—to make this human need to immerse and to almost dispose our 'self' temporarily. It's related to biological needs. That's why we go to the cinema. That's why we read books. That's why we need fiction.

RJSo what will we see in your VR?

AWIt's in the early stage. We're starting with the concept and then we'll approach companies.

RJWhat is your approach to blockbusters, particularly since you have worked with an Academy Award-winning actress in your latest film?

AWThe way I worked with Tilda was personal and I don't want to put too much pressure on myself. I always approach my work with joy and pleasure. I think that making a Hollywood blockbuster would be very stressful.

I do feel that studios in Hollywood have expanded their interests over the years. There are so many niche audiences appearing, so perhaps in the end it's not me who is adapting, but the Hollywood studios that are adapting to experiment with different interests that are emerging.

RJYou do like Steven Spielberg, especially Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and War of the Worlds (2005) with Tom Cruise, so you definitely don't look down at blockbusters.

AWNo, they're very important.

RJWhat do you see yourself doing in ten years?

AWI try not to project. There's a danger when you tie yourself with a profession. It's about cementing your identity to what you can do. But, what if in ten years, I cannot, for whatever reason, do film? If I labelled myself as a filmmaker, I would feel very traumatised. I try not tie myself to any label. And that's the most comfortable approach to life. —[O]