Thao Nguyen Phan: Dangerous Optimism

Thao Nguyen Phan. Courtesy WIELS. Photo: Alexandra Bertels.

Thao Nguyen Phan. Courtesy WIELS. Photo: Alexandra Bertels.

Lacquer, watercolour, and moving image make up the 'theatrical fields' of Thao Nguyen Phan—subtle bodies of work that shift across references from literature, history, and everyday life to address global realities. With Monsoon Melody on view at WIELS, Brussels, her largest solo exhibition to date, Phan discusses her transition to film to explore colonial legacies and ecological destruction in Vietnam.

Phan's recent transition to film was anticipated by an established painting practice, which began with her studies at Ho Chi Minh University of Fine Arts, followed by a BFA at LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore and an MFA in Painting and Drawing at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. Through a lightness of touch, Phan carries weighty subject matter into the realms of poetry and storytelling, allowing arresting visuals to communicate topics ranging from ecological destruction to colonial legacies.

For Tropical Siesta, Phan's first film created in 2017, the artist gathered a group of children living in her husband Truong Cong Tung's village to enact observations from The Travels and Missions of Father Alexander de Rhodes in China and Other Kingdoms of the Orient by French Jesuit missionary Alexander de Rhodes. In a landscape where, as the narrator describes, 'time is frozen in endless tranquil rice paddies', and where the only building is a 'school named "Alexander de Rhodes"', these children 'perform' observations from de Rhodes' account, shifting colonial violence into a realm of make-believe where the past is open to new possibilities.

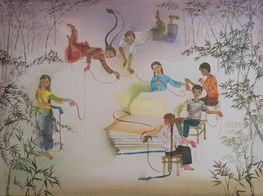

Tropical Siesta is currently on view at WIELS in Brussels, for the artist's largest institutional exhibition to date: Monsoon Melody (1 February–16 August 2020). In two rooms either side of the projection, pages from Alexander de Rhodes' book jut from the walls at various heights, encased in glass and overlaid with watercolour paintings of everyday moments, rituals, and play between children, with violent disturbances—bodies falling from monuments, to marching figures carrying a flag that reads 'WHITE OPTIMISM'.

The way that I approach film and video is similar to the way a painter might approach their canvas—I'm more guided by painting theory.

Through her work, Phan captures historic and present upheavals that haunt the future of Vietnam, as seen in her most recent film, Becoming Alluvium (2019), which was first presented at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona (16 November 2019–6 January 2020) as a result of the artist's 2018 Han Nefkens Foundation – LOOP Video Art Award, and will travel to London's Chisenhale Gallery (26 September–6 December 2020) after showing at WIELS.

In Becoming Alluvium, slow shots reveal the violence of accelerated development, from the building of hydroelectric dams to deforestation, accompanied by narrated excerpts from literary references such as Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, The Lover by Marguerite Dumas, and an anonymous Khmer/Cambodian folk tale of a princess whose impossible request for a necklace made from dew is used as an allegory for human greed. The film is accompanied by lacquer and silkscreen paintings, one of which—part of a series titled 'Perpetual Brightness' (2019–ongoing)—features a ring of schoolchildren standing on a whale, their arms crossed over one another and pouring dark red wine in unison on its inert body.

In this conversation, Phan discusses transitioning from painting to film, children as narrators in her work, and navigating the 'dangerous optimism' of her home country to reflect on the human condition.

TMYou studied an MFA in Painting and Drawing at the School of Art Institute of Chicago, and your practice has since expanded to moving image. When did that shift happen? What led you to start working in film?

TNPIn Vietnam we don't have a lot of contemporary art and the art education there is still very traditional, mainly focusing on painting and sculpture. At the school I went to in Ho Chi Minh, abstract painting is not allowed. If you go to a fine art school, you have to make representational paintings and sculptures, so when I went to the U.S. to do my MFA, many new media were introduced to me. In Vietnam, when I started to go to university, the artists outside of the school were experimenting with media art and installation, but they are not accepted by the institution. When I went to the States, I felt that those media were very welcome in museums.

I want to criticise the desire to be brighter and better when the consequences might not be either of those things—there's a kind of negativity implied in that.

I started to be very interested in making videos when I got to know the work of Thai artist and filmmaker, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who graduated before me from the School of Art Institute of Chicago. I got to discover his work and became more interested in his practice as a visual artist, because aside from his feature films he also makes video art, photographs, and sculptures, and the subject matter relates to the culture and vernacular knowledge of Southeast Asia. In 2016, I got into a mentorship programme called the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative, and I got to be the mentee of American performance and video artist Joan Jonas. I was really inspired by her way of working with the performative and the theatrical, moving image. After meeting her, my practice expanded from painting to video.

TMMute Grain (2019) is split across three screens, juxtaposing imagery that is very rich; almost tactile—a quality that contrasts to the erosion of humanity that this film addresses through its account of the 1945 famine in Vietnam. Becoming Alluvium (2019), on the other hand, is made up of slower shots that pass before the viewer in a way that is starker; more factual. How has your approach to moving image developed over the last few years, technically speaking?

TNPThe way I make films is very intuitive, because I wasn't trained in filmmaking. I learn from watching other video artists and independent filmmakers. The development of technical equipment has given me a certain freedom. The way that I approach film and video is similar to the way a painter might approach their canvas—I'm more guided by painting theory. I am also interested in storytelling; I always want to tell stories, but because I know there is a limitation with words, I always choose a visual way to do so. My first true video work was Tropical Siesta (2017), for which I used adaptations from literature and historical references with my own writing to make a kind of semi-fiction or semi-documentary. That is also when I started to work with children actors, and that carried on in Mute Grain and Becoming Alluvium.

TMDoes that intuitive process begin with literary references? Mute Grain (2019), for instance, is built from a short story by To Hoai that you read as an adolescent, titled Starved.

TNPAll three projects relate to a certain subject matter, such as the Mekong Delta and its mythology in Becoming Alluvium; Mute Grain with a specific, historic famine, and Tropical Siesta with the history of the Romanised script in Vietnam. I do a lot of academic or artistic visual research of the subject matter and through that—through images I've seen, people I've met, books I've read, and sites I've visited—I develop sets of visuals that I translate into drawings and paintings, and the imagery that I create through the paintings and drawings finds its way into video.

TMThe films are told through the perspectives of children, and children are present in your paintings, also. These children amplify the beauty of storytelling, and they remove a certain weight from topics that you deal with, such as the 1945 famine, or colonial histories in Tropical Siesta, but without reducing their urgency. In reality, children might be considered unreliable narrators, however. Where do you place them in your work?

TNPAt first, the decision was also intuitive, because I started to make Tropical Siesta when my daughter was around two. She started to pick up language, and at the same time I was thinking about how I could tell her about all of the problems and issues that adults have created in the past and that are still going on in the present. Secondly, because I'm tackling weighty subject matters, I don't want the work to be so heavy. When I met the children actors in the countryside where my husband's home is, I really liked how they were playing, and I developed a method to use their play in my work, transforming it into a more problematic subject matter.

TMIn a statement for Becoming Alluvium, you have expressed that the film is your attempt to 'collect testimonies for the captured sediments and the variety of species that are sacrificed for human's constant seeking of perpetual brightness.' I'm interested in your use of the term 'brightness' here, instead of, say, 'progress'. Could you tell me a bit about that?

TNPWhen I think about brightness, I think a lot about the medium of lacquer. I collaborate with my husband to create the lacquer works, so it's a conversation between us. Also, lacquerware is supposed to be viewed in darkness—the original colour is usually black, deep red, or deep brown, and when you add a little bit of eggshell to make white, or a little bit of gold leaf, that kind brightness pops up and shines. I feel like it's a kind of metaphor for something that can shine in the darkness.

Through rediscovering these cultures and folk tales, I also learnt about the locals' views of climate change, and the relationship between people and animals.

There is a desire for economic development in the Mekong Delta region, and that region was very pristine and untouched for some time. Now, all of the surrounding countries—China, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand—are wanting to accelerate the speed of development, so things are built too fast. The environment is destroyed in the process of seeking a brightness that is overriding and very flat. I want to criticise the desire to be brighter and better when the consequences might not be either of those things—there's a kind of negativity implied in that.

TMThat flatness reminds me of an excerpt from The Lover by Marguerite Dumas, read by the narrator in Becoming Alluvium, who declares that 'there are no seasons in that part of the world, we just have one season, hot, monotonous, we're in the long hot girdle of the earth, with no spring, no renewal'. This sense of discomfort also translates to what you describe as 'dreadful optimism', in relation to your film Tropical Siesta.

TNPTropical Siesta is set in a fictional school, where all of the kids are self-sufficient—they make their own food and do their own studies. In Tropical Siesta, you can see the children dancing with LED lights in the shape of sunflowers, which I use as an iconography for the ideology and the hope that they symbolise. I also realised in Vietnam that, because we started to open up and people are wealthier and no longer hungry, there is a certain kind of optimism, because they think that the dark times are over and that they can start again, and things will be better. I feel there is a dangerous optimism in that.

TMBecoming Alluvium is anchored in the Mekong Delta and traverses issues ranging from the building of hydroelectric dams, unsustainable agriculture, overfishing, the economic migration of farmers to big cities, and so on. Ecological destruction encompasses so many things, and I imagine that making work about it is a little like opening a can of worms—you discover one issue related to the Mekong Delta, and further downstream, another arises. I wondered if you could discuss how ecological responsibility translates to artistic responsibility, and what challenges you might have come across in storytelling and visually expressing these issues?

TNPI consider Becoming Alluvium an ongoing piece, and I learn new things as I make it. For example, I started to research more about folklore and oral literature from the region, because I'm from Vietnam, but I have no idea about the folk traditions of Laos—we are neighbours, but we're so far apart. We are dominated by the cultures of other places, such as America and Europe, so when I started this project, for me it was a rediscovery of cultures that are close yet very distant. It's a very strange feeling. Through rediscovering these cultures and folk tales, I also learnt about the locals' views of climate change, and the relationship between people and animals. The solutions are somehow already embedded in tradition, but people forget, ignore, or erase them because they want to have a more civilised, modern version.

TMHow have your travels in the region changed your sense of identity, or your perceptions?

TNPI think my artistic perceptions really changed when I started to go to the countryside where my husband is from. His family has a small coffee farm in a very remote area in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The main ethnic group in Vietnam are the Kinh, which is almost 90 percent of the population, but we also have 54 other ethnic minorities, who live in the Highlands and other remote areas, and the farm is one of those places, where the Jarai people live. When I went there, I saw the destruction caused by coffee and rubber farming. I felt those changes deeply when I started to be in touch with the Jarai people, who are native to that area, because their philosophy of living—in the ways they think about and treat nature—is so embedded, and they have so much knowledge that is ignored. That knowledge, and those ways of treating animals with so much respect, changed my way of thinking about the work in a more gentile, respectful way.

TMI understand that you do a lot of work with local communities as part of the artist collective, Art Labor. I wondered if you could please tell me a bit about your work collective? How does that sit within your overall practice?

TNPThere are three of us in Art Labor—myself, my husband, Truong Cong Tung; and my curator friend, Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran. We started the collective in late 2012, when we felt that in Vietnam there was a lack of collective practice that could connect visual arts with other disciplines. When we started, we wanted to work with doctors and anthropologists, and we started a project called Jrai Dew in the village I mentioned earlier. In the project, we work with Jarai artisans who make wood sculptures originally for funeral rituals. We exhibited the work inside the villages where the artisans live, and through those practices we wanted to learn and expand our knowledge about our own country. We also wanted to learn about the practice of growing coffee, because in Vietnam we are the second largest producers of robusta alongside Brazil. For robusta to be so cheap, we have to sacrifice a lot of our rainforests, and it is very unsustainable; the price is always indicated by a market in London, which is really weird, because it affects people in tiny villages, so far away. We wanted to bring awareness around these issues to people, to consider how we can be more sustainable in a creative way.

TMAre you researching any other histories or geographies at the moment?

TNPAt the moment, Becoming Alluvium is a new beginning, and I really want to expand it in a more comprehensive way. I think the way that I use painting and video will develop into a signature style, and the storytelling will continue to evolve. I'd like to do an expedition, maybe upstream, to discover more of the history behind the Mekong Delta. —[O]