Artists in Myanmar Respond to the Zeitgeist

It has been six months since Myanmar's military seized power from elected-leader Aung San Suu Kyi on 1 February 2021, announcing a year-long state of emergency that ended a decade of democracy and prompting waves of protest.

Khin Thethtar Latt, Losing Identity Series, 3 (2021). Digital print on archival paper, edition 1/10. 76.2 x 91.4 cm. Courtesy Karin Weber Gallery.

The online group exhibition Myanmar Voices: We Are Still Here (15 July–15 August 2021) at Hong Kong-based Karin Weber Gallery is a declaration of solidarity and support as artists continue to produce artworks in a difficult political environment, overcoming a range of obstacles including power cuts, lack of supplies, and growing threats of censorship.

A strong sense of symbolism abounds in the work of 14 emerging and established contemporary artists working in Myanmar, like Bart Was Not Here, Htein Lin, Min Wae Aung, and Soe Yu Nwe, as well as those who remain anonymous for fear of retribution.

In the past, '[Burmese] artists quickly figured out how to paint in a coded language that would bypass the censors but still convey a certain meaning to a domestic Burmese audience,' explains the show's curator Melissa Carlson.

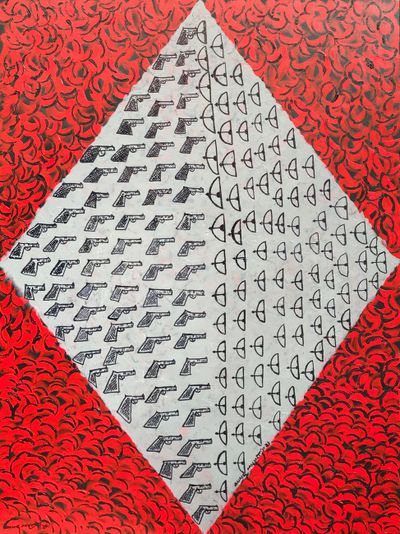

Aung Myint's acrylic on canvas Guns & Arrows (2021) draws parallels between the present and the country's 1988 uprisings that ended with a bloody military coup, during which military soldiers battled civilian guerrillas. Blood red circles are sprayed in front of a muted dark grey-black landscape, as a bullet hole, a symbol of military presence and violence, comes into view just beyond the canvas's centre point.

Known as a forefather of abstraction in Myanmar, Carlson explains that Aung Myint has since departed from traditional paintings of monks, rice paddies, and Buddhist ceremonies, once supported by the socialist government of the 1960s to 80s, signalling a shift in viewpoint.

Aung Myint's most recent piece, the acrylic on canvas Guns & Arrows (2021), leans into a more two-dimensional style, with a repeated pattern of guns pointing to wooden bows and arrows enclosed by a blood red diamond. The work draws parallels between the present and the country's 1988 uprisings that ended with a bloody military coup, during which military soldiers battled civilian guerrillas.

Back then, Carlson notes, safe havens for expression emerged during the Socialist era (1962–1988) 'in private homes of diplomats and artists' across the country, where exhibitions were hosted in a bid to avoid regulations.

As one anonymous artist noted, 'history in Myanmar repeats'—a sentiment that has become ever-present in the shared artistic styles of the community.

Today, many artists have changed their phone numbers and removed their names from social media profiles amid internet crackdowns, with abstraction and ambiguity becoming necessary as the risk of prosecution has heightened since the recent power grab.

In Kaung Su's Forever Strong (2020–2021), graffiti, pastel, charcoal, and oil paint come together on canvas to reflect an air of defiance. Frantic black brushwork envelopes a single figure with a shadowed face surrounded by red crosses and star signs—symbols of death paired with the national flag, as well as abstract sketches of resilient fists.

The beauty of a group show is safety in numbers, emboldening artists to communicate not only with local and national communities, but with a global audience as well.

Capturing the daily lives of Myanmar's citizens today is a documentary photography series by Khin Thethtar Latt (Nora) titled 'Losing Identity' (2020): a narrative of family portraits, crowded street images, and intimate settings at home, where every face is blurred in red.

That blurring of identity is also reflected among the artists in the show who remain unnamed, perhaps so that they might be bolder in their communication. Take two acrylic on canvas paintings We Are Hungry (2021) and We Want Democracy (2021) by one anonymous artist, which act as a reminder of the importance of free artistic expression and courage in the face of political oppression.

The former shows three kneeling and squatting human figures with open mouths, as bold text reads 'WE ARE HUNGRY', while the latter depicts nude bodies rendered in large brush strokes: a reminder of the decades of military rule when nudity was banned.

As one anonymous artist noted, 'history in Myanmar repeats'—a sentiment that has become ever-present in the shared artistic styles of the community.

With that in mind, late artist Myint San Myint, who sadly passed away from Covid-19 in July, said shows like Myanmar Voices are of particular importance when it comes to confronting real-time violence: 'I don't want my work to be like a soft flower but a sharp knife that can get rid of injustice.' —[O]