Hu Wei Treads the Ruins of Modernisation

Hu Wei. Courtesy the artist.

Hu Wei. Courtesy the artist.

'I consider my creative process a combination of being lured and setting decoys,' the artist Hu Wei says in discussing his latest exhibition.

Traversing a range of topics from Pacific Ocean inhabitants to a quarry in Hong Kong and a politically charged espionage case, Hu Wei's practice combines extensive fieldwork, archival documentation, and fiction.

Currently on display at the Macalline Art Center in Beijing, Touching A Fabric of Holes (21 May–3 September 2023) presents three recent projects that combine installation, sculpture, and film to capture the spirit and physicality of individuals entangled in the intricate web of society and history. The artist uses deliberate arrangement to drop hints, inviting viewers to consider concealed and exposed narratives.

Walking through the institution's spacious, dim-lit room, viewers first encounter Long Time Between Sunsets and Underground Waves (2020–2021), a single-channel film displayed on a cinematic-sized screen.

The film results from Hu Wei's 2019 residency on the island of Pulau Dinawan, Malaysia. It combines documentary and fiction, offering insight into the history, life, and struggles of the Bajau people—stateless islanders known as sea nomads—and their intertwined relationships with nature, legends, and oceanic politics.

The film is complemented by Aquatic Invasion (No.1-No.6) (2021), a series of translucent, dysmorphic sculptures scattered on the floor before the screen. Nearby, the hanging installation In the Belly of the X – Double Headed (2021), made of bronze, steel, resin, and crystal, represents the legendary sea creature Makara from Bajau folk culture inside a whale.

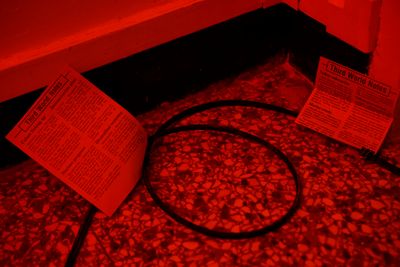

At the centre of the exhibition space, three wide steps lead to a large, red-lit makeshift room. Inside, a trench coat hangs on one wall with a password-lock briefcase below. Framed physical examination documents are presented on the opposing wall. At the farther end, the two-channel film The Almost Perfect Crime (2022) hovers above an oscilloscope installation, presented against a one-way mirror wall.

The work is based on the sexual affair between French diplomat Bernard Boursicot and Peking opera singer Shi Pei Pu in the 1960s. While Boursicot was under the impression that he was with a woman, after 20 years, Shi was revealed to be a man and a spy who obtained secrets from Boursicot.

The affair inspired American playwright David Henry Hwang's work M. Butterfly (1988), which became a major hit on New York's Broadway and was adapted into a 1993 movie of the same title. Under discomforting red light, juxtaposed screens present actors portraying Shi and Boursicot, who each narrate the story from their own perspective. It is a skilful weaving of history, theatre, personal memory, and fiction.

The exhibition concludes with Hu Wei's latest work, The Rumbling (2023), a three-channel video focused on an abandoned quarry in southern China, tracing the history of mainlanders illegally escaping to Hong Kong in the 1990s.

Unable to be viewed simultaneously from their placement on different walls, the central screen narrates the ebbs and flows in the quarry's history, while the projections on either side depict a relatively blurred image of an anonymous man fleeing to Hong Kong and shipping routes from mainland China to the latter.

In this conversation, the artist discusses with Sun Wenjie the works in this show and how he explores the potential of expanded cinema, his long-term interest in individuals that have been erased, silenced, and marginalised, and how history might provide insight into our present.

Sun previously curated the artist's work, featured in the show The Long Way Around with Xiang Kaiyang at ShanghART Beijing in 2021 and 2022.

SWCould you talk about the title of the exhibition? The Chinese title 诱饵 (decoy) seems unrelated to the English title, Touching A Fabric of Holes. How are they related?

HWDecoys usually refer to man-made baits, often in the form of ducks, used in game hunting to lure, trap, or kill animals. In this context, I use the term to represent a mechanism that catches. As for the English title, Touching A Fabric of Holes, it also alludes to a type of trap, perhaps a net that ensnares us all. I see it as a metaphor for the relationship between individuals and greater, unseen powers.

My creative process is a combination of being lured and setting decoys. On the one hand, I'm fascinated by the enticements that draw my attention and guide my exploration, be it a historical event or research on silenced or erased materials. Some decoys are intentionally placed, while others occur by chance—much like when hunting in the woods, not knowing what prey might pop out.

On the other hand, I might also be setting the bait through my work. The three projects in the exhibition draw inspiration from reality, but the stories have been re-scripted and the images manipulated. Isn't this fictional narrative some trap for audiences? I find myself both hunting and being ensnared in the process.

SWYour latest work, The Rumbling, is a three-channel video with screens positioned to prevent simultaneous viewing. The main screen at the centre follows a man who runs a small inn on the island, while another main character—the owner of a now-abandoned quarry—is depicted only through the man's words. Could you tell us more about these two characters?

HWLao Huang opened a humble inn on the island, probably the first of its kind there. Initially, communication with him wasn't so congenial because he was quite passionate about the leadership of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party].

However, after spending some time with him during the filming process, he gradually opened up and shared that he had also attempted to escape to Hong Kong in the past. This revelation allowed me to engage in meaningful discussions and let him know what I wanted to convey in the film.

In his earlier years, Lao Huang served in the navy and was stationed at Shatoujiao in Shenzhen, which used to be one of the final escape points for people fleeing from the mainland to Hong Kong. Following his discharge, he moved to the island and worked for the quarry owner for several years. He had contemplated sneaking into Hong Kong as well but ultimately refrained.

To me, Lao Huang possessed the qualities of an excellent storyteller, having witnessed the quarry's fluctuations from its booming period in the late 1980s to its closure in the early 2000s, followed by the owner's sudden disappearance.

Since my filmmaking approach heavily involves physical presence and on-site engagement, I decided not to use an actor but to persuade Lao Huang to portray himself. Although this decision presented some challenges, as I was shooting on Super-16mm film, which makes trial and error very uneconomic, it turned out to be a success.

I think of these projects as different signs of ruin or decay.

Through Lao Huang's narration, the quarry owner's story gradually unfolds: escaping from Hunan province to Hong Kong in the 1960s, he returned in the 1980s to invest in mainland industries, enticed by Chinese economic reform policies, and then fled again shortly after the handover of Hong Kong, for reasons unknown. I find this element of suspense intriguing.

The quarry's business was fuelled by the urgent need to transport stones to Hong Kong for sea reclamation, reflecting the economic prosperity of Hong Kong in the 1980s and 90s, as well as its claim on resources from neighbouring areas.

What was known as the refugee wave from mainland China to British Hong Kong was ultimately driven by a desire for freedom and wealth. I perceived a parallel between this migration and the stone blasting procedure, causing shocks and vibrations akin to a tiny earthquake. The Rumbling refers to this reverberation formed by the compression of the underground strata—a thundering, telepathic resound we might sense before geologic, political, economic, or personal earthquakes.

SWThe vertically positioned screen shows a rotated sea horizon with water flowing downwards. This imagery of the sea is present across all three projects in the exhibition. It becomes an encompassing symbol of maritime trades, blue civilisation, stowaways, or the declining, poetic image of the ocean in a literary sense. What draws your focus to the sea?

HWFor me, the sea represents imagined movements and migration pathways. It's difficult for those living on land to fully grasp what transpires in the sea, from trade routes and the submarine-optical-fibre-cable system to the existence of mysterious and peculiar-looking creatures.

My walking experience in recent years has mostly been in coastal or island regions. However, I am cautious not to portray the sea as static imagery; I intend to delve into more substantial, solid issues. In this case, while footage of the sea appears on different screens in my work, each screen manipulates the imagery differently.

For the vertical screen, I used a rotating mirror device while capturing footage of the rocks and sea reflected by the mirror. This technique sometimes induces a sense of dizziness in the images. I aim to soften or blur the narrative rather than using documentation of grand industrial reclamation projects.

The sea I filmed was on an international freight route; numerous freighters navigate this route, transporting containers from Hong Kong to various destinations worldwide. I wanted to draw a comparison between the trade paths of goods in the present and the trajectories of people struggling to cross the strait in the past.

There is a stark contrast between colossal freighters and individuals making their daring escapes. However, I prefer to depict these connections in a subtle, abstract manner, evoking a sense of decay. Hence rotating the screen allows the water to sink, elongate, and resemble a wormhole almost.

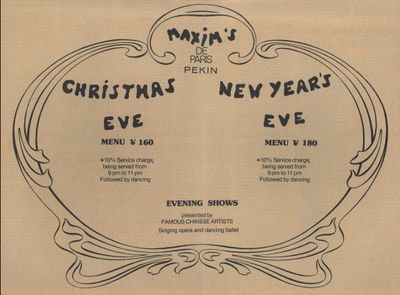

SWIn your studio, I saw clippings about balls and parties at the famous Maxim's restaurant in Paris, which you collected for the making of The Almost Perfect Crime. As you study the subjects, you build a large collection of archival materials, but may eventually use only a small portion of it. Can you talk about your collection of archives?

HWThe Almost Perfect Crime is an investigation and fictionalisation based on factual materials of an unspeakable, convoluted espionage case and international love affair during the Cold War. Before the shooting process, I collected a lot of Chinese and Western newspapers from 1987, based on which I worked on the script and related texts.

I also mean to trace the transition in foreign policies and the easing of ideological tensions from media reportage. In barely noticeable places, you may read about current affairs in third-world countries from a Chinese perspective. And the layout always has to do with Cold War ideologies.

Why newspapers from 1987? Because that was the year Shi Pei Pu was pardoned. It was towards the end of the Cold War, and the French government sought a friendly relationship with China. Trades between the two countries were booming, indicated by advertisements in the papers for investments in and trades with China.

The balls and parties at Maxim's were advertised in the same period, and the information on it seems to beautifully match the story of Shi and Boursicot—one could easily imagine a Chinese opera singer from the East and a French diplomat meeting at such a party. I am deliberate about presenting such an interesting mismatch.

The text I created for this work integrates journalistic reports, interviews with the two perpetrators, forensic evidence, and my own fictionalisation of the story. While David Cronenberg's M. Butterfly certainly influenced it, my film is essentially an epilogue: it portrays the two protagonists being arrested after settling in Paris, performatively recollecting and confessing how their intimate relationship eventually became alienated.

SWThe history upon which The Almost Perfect Crime is based was a cause célèbre: not only was it a Cold War-era honeypot trap that involved two big countries and a remarkable espionage case, but it was sensational and public enough to be made into a play on Broadway and later a film in Hollywood. What did you mean to achieve with a new interpretation?

HWI'm interested in exploring silenced histories. I thought Cronenberg's romanticisation of David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly, especially the ending of a story like that, was vastly different from what I wanted to do. But I was not going to ignore the film; acknowledging that adaptation, I was trying to consider expansions and further developments.

I want to revisit this incident without abusing nostalgia or indulging in stereotypical depictions of the East or women, especially in the New Cold War situation that has been emerging in recent years. I was captivated by the case primarily because of its rich and convoluted nature, such as the deep ideological conflicts revealed by Chinese and Western reportage and reactions.

One intriguing detail was the pseudo-scientific racism exhibited during the French authorities' examination of Shi's body, where they apparently believed his gender was crucial in defining the nature of the case. Examining this historical aspect in light of our time, one might quickly claim that society has become more tolerant, free, and equal today, with greater recognition and acceptance of gender fluidity.

I want to revisit this incident without abusing nostalgia or indulging in stereotypical depictions of the East or women.

Yet, it begs the question: Is it still possible to solve an espionage case solely based on one's gender and reproductive organs? Such an approach is questionable. We may have made progress, but why are Cold War spectres re-appearing? It suggests that deeply rooted, immovable, inflexible, and insolvable oppositions may persist.

The projects included in Touching A Fabric of Holes all revolve around historical and suspended cases, with each story unfolding between the 1960s and 90s, a relatively short period in which the development of modernisation turned itself into ruin.

I think of these projects as different signs of ruin or decay. Within this decay, we find shattered souls, the devastation of nature, and displaced individuals. I aim to explore ways of piecing together multiple time dimensions and visual forms to conceive a sense of equilibrium amid the decay.

SWSpeaking of films, you have been mostly creating in this form in the last two years and a half, and the current exhibition also revolves around films. But you often say that you don't want to be a film director. Why is that?

HWMy disinterest in becoming a director stems from my lack of inclination towards producing feature-length films for commercial distribution in cinemas. While I have taken on the role of director for the three films featured in the current exhibition, the process of creating these works differs significantly from conventional filmmaking methods. Instead, I place considerable importance on the spatial and performative aspects of the artwork and the viewing conditions surrounding it.

In making The Almost Perfect Crime, for example, I was intrigued by questions like what archival materials shall be made available on-site. How do they perceive the authenticity or manipulation of the documents presented? How do they read and judge the content and testimonies? How do audiences condition themselves mentally and psychologically as they watch the film and navigate the red-lit space?

SWLong Time Between Sunsets and Underground Waves is paired with two sculptures, In the Belly of the X – Double Headed and Aquatic Invasion (No.1-No.6). How do they resonate with the film?

HWThe film explores the world through the eyes of an unknown species observing the transformations of geoengineering projects, Bajau animism, and non-human elements. Gradually, it transitions into a work of fiction, resembling a deep diver or sea nomad.

The sculpture In the Belly of the X – Double Headed captures the imagined form of the Makara, a semi-divine amphibian creature present in local animism, known for traversing lands and oceans.

The Makara represents the beliefs and actions of the Bajau people, who avoid entering forests at night, fearing the presence of ghosts. The weak light projected onto the sculpture evokes a phosphorescent aura reminiscent of the mysterious atmosphere in a dark forest.

SWThe three independent projects all deal implicitly with identity. I notice that none of the characters appears to question or struggle with their identities; they seem to accept the givens as if by default. Could you speak about this?

HWI am rather pessimistic, but I am not going to impose my pessimism or pain onto the characters. I have come to realise that they are not the focus of my work. My approach is very different from the cinematic portrayal of well-defined, personality-driven characters. The characters in my works are melting in their own times, or becoming emptied vessels exposed in nature, their corporeality vanishing in history.

In The Rumbling, I explore the concept of crushing compression in both geologic and anthropocentric terms. The notion of ghost strata, as proposed by Polish geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, refers to missing elements within rock strata that offer clues about what once existed there. In essence, rocks themselves are transient, existing for a limited period. This idea resembles an invisible-yet-omnipresent projection, representing the accumulation of Earth's history.

From a geological-time perspective, geoengineering could be considered a process of spectralisation. I think it works well in parallel with the movements of migrants who briefly stay on the islands—crossing borders with stones from the quarry, sinking, disappearing...

During the creation of The Rumbling, I collected blasting permits from the island. On one permit, the photograph was crossed out, possibly indicating that the person did not successfully reach Hong Kong.

This inspired my narrative approach, emphasising the materiality of the Super-16mm film I used by physically crossing out faces. Those individuals who were crossed out on blasting permits are akin to the ghost strata that erode over time. —[O]