Mithu Sen on Art, Poetry, and Lingual Anarchy

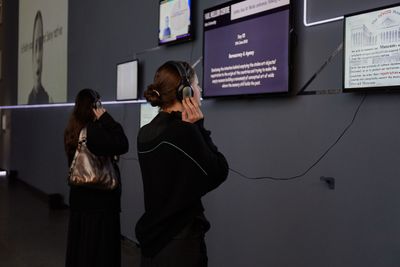

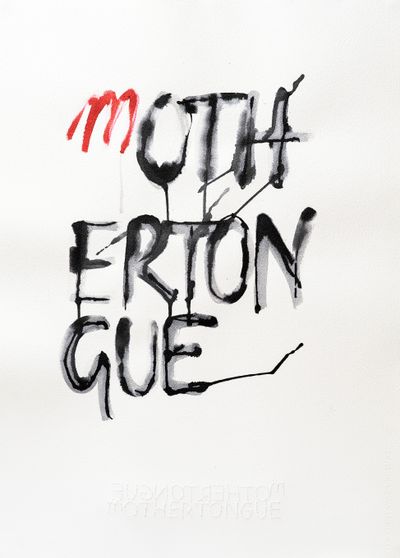

Mithu Sen. Opening event: Mithu Sen, mOTHERTONGUE, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (22 April–18 June 2023). Photo: Casey Horsfield.

Mithu Sen. Opening event: Mithu Sen, mOTHERTONGUE, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (22 April–18 June 2023). Photo: Casey Horsfield.

I met artist Mithu Sen in New Delhi during India Art Fair in 2011, when she was awarded the inaugural Skoda Prize for Indian contemporary art for 'Black Candy (iforgotmypenisathome)' (2010), a series of drawings whose hilarious, irreverent subtitle pokes fun at the patriarchy. A trophy was bestowed on her by Anish Kapoor during a lavish ceremony with guests resplendent in bejewelled saris.

A teasing trickster, Sen is adept at deploying language to undercut and subvert rules and hierarchical codes in the art-world system, whether by hacking her own Wikipedia entry to announce her participation in 'Documenta 26', lecturing in gibberish as part of the performance Aphasia (2016) at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, or zoom-bombing a Yale University art forum for Be beyond being (2021).

Video documentation of both interventions feature in Sen's major solo exhibition mOTHERTONGUE (22 April–18 June 2023) at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), Melbourne. Curated by Max Delany, ACCA Artistic Director and CEO, the exhibition traverses the historiographies, satirical polemics, and exoticising discourses that Sen has long confronted.

Among visceral works on view is Sen's early video performance, Ephemeral Affair (2006), in which the artist is recorded flinching and contorting her face while being tattooed, but we cannot see her skin being perforated.

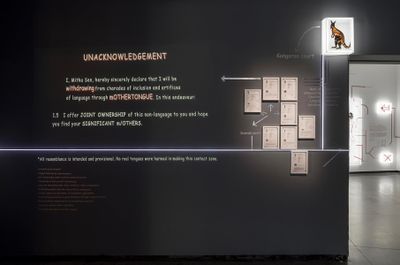

Inducing states of unsettlement and discomfort, mOTHERTONGUE begins with an 'unacknowledgement' by Sen projected on the wall, signalling the awkwardness of Australia's colonial history, complete with word puns. A backlit kangaroo drawing rendered in ink and watercolour hangs nearby (Kangaroo, 2023).

Sen's Un-acknowledgement (2023) questions the role of traditional land acknowledgements, which recognise the Aboriginal custodians of Australian land while amplifying its historical seizure—statements that often emphasise their position as foreign guests in Australia, or a museum.

Intending to make audiences feel uncomfortable, the notion of being 'unwelcome' becomes a form of resistance in Sen's work—a strategy that seeks to undo narratives of power and colonial authority.

In a recent interview, Sen said: 'I believe we are all in a search of mother tongue where we feel comforted.' But to reach that comfort, one must pass through the discomfort of coming undone, which Sen invokes with works that co-mingle language, image, and text in ways that contort syntax and grammar.

Poetry, words, speech, language, and utterances are core dimensions of Sen's capacious practice, which hinges on the artist's notion of 'lingual anarchy'. Nonsensical and profound, her work often incorporates non-verbal mutterings uttered with the cadence and gesture of speech, bringing to light the dominance of English and Eurocentric biases from the perspective of a female artist from the 'Global South'.

During the exhibition's opening week, Sen delivered a characteristic non-verbal gibberish performance lecture devoid of art speak, complete with captivating tonal shifts and gesticulations that irreverently and humorously pointed to the pomposity of academic discourses.

Likewise, Sen revels in new and improvised forms of animated, digital abstract poetry, such as Unpoetry (2018 and 2023), short animations of multi-syllable words that also reside on her active social media and Instagram accounts.

The daughter of a Bengali poet, Sen wrote poems from a young age in West Bengal, India, later publishing two volumes of poetry in Bengali. Poems Declined (2014), created for the second Dhaka Art Summit (2014), comprised a leather-bound volume of 1,800 poems from poets and publishers in Dhaka that have been declined or refused publication, paying respect to excluded voices.

The global dominance of English prompted a number of powerful performances by Sen in gibberish or 'non-language', as noted in UnMYthU: UnKIND(s) Alternatives (2018), first presented at the 2018 Asia Pacific Triennial, which features backlit drawings of skeletons and plants, framed by diagrams illustrating the dynamics of social exchange and a schema with hashtags such as #Dick-Tator and #re(li)gionist.

A video documenting Sen's performance at Queensland Art Gallery accompanies the installation, in which she asks the AI voice service Alexa (2008) questions pertaining to politics and human rights. 'Do you love me?' is met with a garbled response.

This engagement across real and virtual spheres is equally reflected in I am from there. I am from here (2023), first shown at Sharjah Biennial 15. Inside clear resin blocks, real and artificial hair was arranged to form an Arabic poem with an invented and illegible script, framed by emojis, or funny faces, also made of hair.

Of course, mOTHERTONGUE is rooted in Sen's friendship, camaraderie, and relationships with people and place. The exhibition's opening was preceded by a deep engagement with the local arts community, including a four-week residency at Norma Redpath Studio, University of Melbourne.

Since 2011, Mithu has visited Melbourne on five occasions. Over this time, we have forged a profound friendship such that Mithu calls me her 'shadow sister'. I, too, have become spellbound by Mithu's magic, loyalty, and the depth and complexity of her practice that is vulnerable, volatile, and at times, violent.

Her continuous process of unravelling language, playfully making meaning indecipherable through glitches, problems of translation, humour, and improvisation is central to the exhibition. mOTHERTONGUE signals Sen's concept of 'radical hospitality', whereby she subverts the role of artist and museum, host and guest, by highlighting the bureaucratic and contractual language of institutions.

The resulting exhibition is profound and poetic, complex and complicated, aesthetic yet searing, demonstrating an immense creative dexterity when it comes to working across media. In the following conversation, Mithu Sen and I discuss the relationship between art and poetry, the making of mOTHERTONGUE, and the representation of violence and instances of resistance within Sen's work.

NKArt and poetry are intertwined in your practice, given you also write Bengali poetry. Could you discuss the role of language, lingual anarchy, and non-language in your work, and tell us about your mother's poetry and your early writings?

MSMy mother is a poet, so I grew up believing poetry to be my mother tongue. I saw her passion and dedication towards her poetry, which was a ritual for her—she made sure to write something before the day's end. Since childhood, I found this part of her daily routine most fascinating, especially the concentration and clarity with which she worked and the happiness that I saw in her afterwards.

In those moments, I no longer saw her in the role of a mother, wife, sister, or daughter—it was a complete immersion in a 'beyondness'. I didn't know what poetry was then, but knew only poetry gave her that aura!

I started writing when I could hardly write by myself. I created rhymes or composed words and my mother wrote them down and sent them to the children's section of little magazines where she published her poems.

The myth of a mother was reshaped; we became co-poets and that became my mother tongue! I found a home and comfort in poetry, in languages known and unknown.

My vision for mOTHERTONGUE is not nostalgia or sentimentalism. The languages we speak or are made to speak are messy. The crisis of language because of inhabited realities and conventions of postcolonial India has become a colonially mediated culture with an officially mediated tongue where English is a reminder of colonial dominance.

Migration! My destiny brought me to Delhi after Santiniketan, where I felt even more alienated from the Anglophone art world and its exclusivity. There was no solace, no alternate vernacular. The language I knew became meaningless and I came to desire meaning even more strongly, seeking a semblance of it in everything I produced.

I found trouble staking claim to myself, conscious of my perceptible inabilities and how untethered I felt. I started losing my words in Bengali, engulfed by a lingual void and lost to a sense of non-belonging.

Throughout my artistic career, language has always been a point of inflexion in my work. In the last two decades, I have explored this as a strand in my practice, which I now call 'lingual anarchy'.

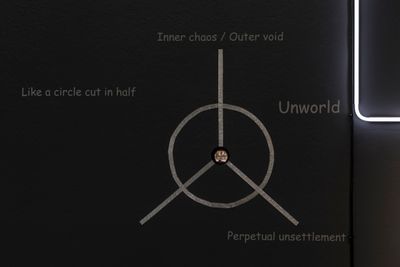

I have created an un-codified, shifting, subconscious language through visual and performative practices that I call 'un-language'. I use 'un-' as a linguistic tool, narrative trope, and strategy. As a prefix, 'un-' is a method to carry out unsettlements. I don't intend to invent a new language, but a counter to language itself.

In this exhibition, 'un-language' stretches across mediums of poetry, video, performance, lecture, contracts, social media, and glitches. It's addressed through alphabets, punctuation, emojis, signs, guttural sounds, nonsensical phrases, and so on. It's the primary material around which everything revolves.

NKCan you tell us how the exhibition came about? How did the mind map become the starting point to configure your artworks?

MSmOTHERTONGUE is conceptualised and developed as one piece of artwork taking the form of a mind map. It's conceived as a trajectory, a chronological disorder with annotations and guiding signs as punctuation and accompaniment via a mind map.

The exhibition space is the guiding marker, an externalisation of my process, a dialogue between internal states of instinct and feeling, and a stream of consciousness for issues of language, identity, colonial domination, and cultural loss.

The mind map focused on a few conceptual areas, such as 'Language of Loss', 'Poetics of Instruction', 'Choreography of Control/Directing Light', 'The Considerations of a Contract', and 'Flattening Time'. My goal was to produce a performance that will not require my presence or guidance in person but can become one with the structure of the exhibition itself.

Performance, however, has a stretchable, contextual meaning to me. There is a multi-directional potential in performance to not only put together one's thoughts but imagine a breach in the inert artist-spectator binary. I consciously place gestures, actions, and words to invite spectators in, allow them to lull their regular cognitive reception, and push for an atmosphere that is more generative and affective.

I framed this exhibition as a contact zone: an open social space where trans-cultural and trans-lingual possibilities are explored through the declarative, performative, contractual, and instructional potential of language, and created a choreography of control using light as a great aesthetic and conceptual device.

The context has been mapped in the form of a narrative; the trail of light plays the role of a guiding line, piercing the exhibition space with a sense of direction and movement. It joins light boxes, videos, and projections, and splinters into nodes of thought that annotate artworks on the walls.

If we see light as a medium in the show, its ability to bend, transfer, filter, and refract is given a more complex purpose as the central line in our sprawling timeline. The notions on the timeline are related to my vision of flattening time or 'untime' to record events or temporal puzzles in a non-chronological manner.

In a formal sense, the frontal wall offers the revelatory key to every aspect of the exhibition. It's through its plotting as a chart, its meshing timeline, the presence of 'I', its piercing lines of light, looping rhythms, and poetic abstractions that it dissolves languages into deeply resonant and perfectly communicable 'other tongues'.

NKWhat about the role of mothering and othering in the exhibition?

MSWhen I conceived of this exhibition as mOTHERTONGUE, I thought about the language split between a mother tongue and 'other tongues'. Mother tongue indicates not just the language you imbibed from your family and regional and cultural location, but a private version of your language and preferred ways of communicating.

I have always felt that my mother tongue was poetry, not Bangla, or English. It was to put a premium on the immediacy and feeling of language and suggest that language has a close generative feeling to people; it's not a structure of the outside world.

The 'other tongues' are the manufactured languages with elaborate grammars and syntaxes that come in the way of our private language and make expression a herculean task. They have to be learned and practised, and their codes reproduce social hierarchies. It is here that I see mothering and othering at work—mothering nurtures, while othering creates barriers whether in the domain of language or elsewhere.

NKThe exhibition begins with an 'unacknowledgement' that points to the protocols of First Peoples in Australia and associated platitudes. How did you compose this work given local sensitivities and your impetus towards making audiences uncomfortable?

MSOver the last decade, contracts have steadily become a fixture in my practice. Every work I produce is now accompanied by a contract, articulating a succinct message nested in the artwork.

I have always felt that my mother tongue was poetry, not Bangla, or English.

Un-acknowledgement returns my practice to the exhibition's raison d'être by tracking my personal history with the contract using contractual language. The contract stands to speak to the contexts of colonisation, cultural subjugation, and dispossession to bring attention to the exhibition's focus: language.

In doing so, I reference the dispassionate heavy-handedness of legal English on one hand, and on the other, official forms, disclaimers, statutory warnings, and public messages—one of these being land acknowledgements.

The ubiquity of contractual undertakings meets the uniqueness of the postcolonial relationship with the 'other tongue' of English. The confluence of these two experiences gets sealed within the contract. Through this, I attempted to draw a bridge between colonised people, whether from India, Australia, or elsewhere.

The work addresses the cultural subjugation inflicted by colonisation and its contiguous agents, implicated within institutions that carry out such acknowledgements as a rite of conscience-clearing. It was an important affinity to underline and a prominent ritual to emphasise.

NKDeadline – extended (2023), the projection of an analogue clock with its hands immobilised over Roman numerals, appears to suggest untimeliness, frozen time, but also the pressures of deadlines, bureaucratic time, and being out of time. Can you discuss this work?

MSAccording to prevailing common sense, it's understood that while we may inhabit different spatial realities, we live at the same time. This, however, is far from the actual experience of our realities.

In the passage of time, I see another language of mortality and meaning that comes to a close as time fades away.

Time moves in compliance with a number of factors, ranging from our emotional trappings to global disorders. The ticking of a clock is an ominous sign that reminds us not only of time's passage but the improbability of our own end.

While time neither begins nor ends, we, as its witnesses, spend a limited period in the wider temporal scheme. As such, in the passage of time, I see another language of mortality and meaning that comes to a close as time fades away. Here, the fading moment is witnessed through the transformation of the clock into a luminescent ring of light gleaming with an uncanny resemblance to an ambiguous planetary form.

Training in the language of time is one of the first big lessons of any child's life. We are taught to read time to calculate how much is left. This daily arithmetic mediated through the clock is the one banal routine that we don't register as particularly ominous.

When we look at a clock, we see a machine: a dial and two hands, numeric code, and movement. We don't see it as a device that accumulates our personal time, tabulating at every moment the limits of our mortality. Time is the indexical language we live in and our entire life is durational. Deadlines are imposed on it.

Constellating these radials of time-bound languages, this clock is a luminescent mirage that references the numeric codes of timekeeping but fades away momentarily, making any reading impossible.

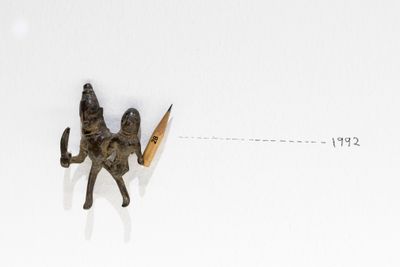

NKYour studio in New Delhi is full of small objects such as talismans or rescued artefacts. How do they relate to MOU (Museum of unbelongings) (2023), an abundant collation of found, miniature objects displayed on a large, rotating circular museum vitrine?

Acquired by Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi, these abandoned trinkets and treasures are laden with memories of forgotten lives.

MSI am a collector of emotions and things—objects, poems, smells, or touches. Whatever I find resonant, I collect. MOU is a personal archive that has no space in official history, filled with abandoned, impermanent toys, unusual belongings, and sculpted objects laden with memory and investment in a musealised showcase.

Time is the indexical language we live in and our entire life is durational.

It's not a repository of conventional knowledge, but a record of life—a history of vernacular culture and a symbolic archive of impermanence, drawn together at a single point in time.

These 'unbelonged' objects in their states of rejection and/or migration speak their histories. As assembled metaphors of possession and dispossession, use and disuse, they piece together the personal and anonymous, objecthood and emotionality, to extend the parameters of mapping and collection towards a politics of empathy and introspection.

It's the politics around the idea of making history and archives: what is chosen to be part of the political, collective, and popular history, and what is suppressed, (un)acknowledged, and (un)seen. I undertake the role of a collector, always absorbing the images, words, and emotions of humankind, seemingly little ephemeral things.

NKThe notion of 'radical hospitality' in your work is a complex relationality that traverses the precarious balance of guest-host relationships. How does this notion play out in exhibitions where you are a guest in a museum or elsewhere?

For example, as part of I have only one language, it is not mine (2014), developed for Kochi-Muziris Biennale in India, you spent several days in a girls' orphanage as Mago, a fictional character who did not speak any of the languages the girls could understand.

Can you tell us about the red, animated video artwork created from these interactions and your conversations with the girls in gibberish? And your role as host and fictional interviewer and whether trust was part of the relationship?

MSThe guest-host relationships that play out in my exploration of 'radical hospitality' are invariably relations of power, and always attempt to draw out the tension between the more powerful and powerless sides.

In the 2014 video for Kochi-Muziris Biennale, I was exercising more power on account of entering an environment for orphans. During my stay, I was known to them as a foreign character—a fate most absurd and an incomprehensible language.

It was not an experiment in social ethnography and I did not undertake a study as a participant-observer. Inserted in a closed world with nothing but an embodied non-language, surrounded by girls curious and cautious about a stranger, led to an extraordinary stay. I made friends despite the barriers of age, language, and temporary stay.

It was built on trust from my young friends, who exist in the video as dissolving red outlines as a counterpoint to my dissolved language. It was on account of trust and faith that my stay and its documentation had to walk a tightrope of binding myself to the same ethical commitments as I was to members of the orphanage. The resulting video is therefore not a documentary.

In the case of mOTHERTONGUE, 'radical hospitality' shaped not just the exhibition but its production and experience. Translating my conceptual vision into the context of Australia, where colonisation has a thriving afterlife in the subjugation of Indigenous people and their culture, including their language, was an affinity point for me—even as the exhibition was hosted in a more rarefied setting.

'Radical hospitality' materialised in patchwork impulses, code-switching registers between 'other tongues' and mother tongue, space and text, and (un)acknowledging neo-colonial frames.

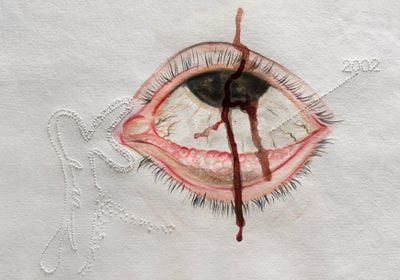

NKYour new suite of drawings mOTHER I SPELL YOU WRONG (2023) includes texts such as 'I HATE PINK', 'I BLEED RIVER', and 'EYEFORGOTYOU', with stains, leaks, drips, and blood-like seepage.

In these language games, there are shifts in registers almost like slogans for political posters that recall Jenny Holzer's Inflammatory Essays (1979–1982). Could you discuss the linguistic shifts in your drawings and the power of language as a slogan?

MSI have been using the language and form of feminist articulation for some time. Between i cunt imagine (2010) and mOTHER I SPELL YOU WRONG, projects such as UnMansplaining (2019) enacted the impulse at the heart of such projects: to channel anger in a different vocabulary.

I'm not interested in tired clichés; there are political activists who do a better job of repeatedly reminding us of what is at stake. As an artist, I try to find new ways to speak and challenge, and new languages to inhabit and mutate.

mOTHER I SPELL YOU WRONG takes after corruptions of language mixed with a dose of internet shorthand. For Sharjah, the alphabet only appears to be Arabic. When I work in the form of 'un-language', what becomes apparent is not the fact that there are people who don't want to pay heed to critique of various inequalities. Instead, you can see that your concerns get taken seriously only when they are communicated in English.

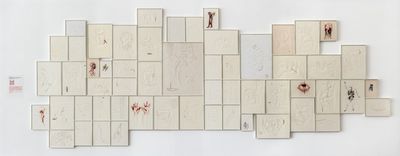

NKYour oblique representation of violence appears in works like Until you 206 (2021–2022), 56 watercolour-and-ink drawings with tiny pinpricks or perforations denoting the years of violent events since India's Independence.

Can you tell me about the non-representation of violence, pain, and persecution in your work, and the pervasive use of a blood-like red?

MSI didn't want to reproduce scenes of violence by creating a representative mosaic of violent acts. I think today's media machinery does that to the point that images of violence seem to no longer rankle people.

I wanted to distil violence in a language as stark and clinical as possible, to find a correspondence between acts of violence and acts of representation. In doing so, especially during the pandemic, I was told that what people want is to look at images that are happy and pleasing.

In response to this desire for dissonance, I started creating perforated drawings. The process of making these works was violent but passive and stayed as a reminder, preserving the medium's purity, yet persistently puncturing it.

The redness is not so much an indication of expected associations—blood, danger, and flesh—than a long-standing part of my palette. Here, I use red for its starkness, both in itself and against the pristine white. The saturation between the two colours dramatises the conflict between purity and complicity that I intend to stage.

NKTwo adjacent films featuring birds are also on view at ACCA: Pigeon (2023) comprises a pigeon breathing slowly on a window sill in the rain with its head obscured; in Icarus (2006–2007), a stillborn bird foetus is devoured by ants with imperceptible movements.

These films seem to have aching tenderness but also revulsion and violence, which reminds me of your poem 'Doel, Sparrow' (1995–2005). Can you discuss these achingly sad bird films?

MSOf the two, Icarus is my oldest work, shot on a morning after a storm in Bahia, Brazil, in 2006. It documents an army of ants lifting the corpse of an embryonic bird. Its unformed wings are unwittingly animated by their movement, so the dead bird appears to be in flight.

At home, in Delhi, my studio is visited by birds; many pigeons stop by on the highest stories midway through their journey across the city. In the body of a pigeon attuned to flight, movement and breath combine in stark moments of flight or stillness.

In this pigeon video, there is the register of the surreal, where the rhythm of its breath echoes the city's cold, dust, and pollution. Its otherworldly quality is accentuated by its hidden head and the ghostly expanse outstretching from its perch.

Breath is visceral. It moves through our body, shifting in scales and tonalities as it is produced. This deeply internal labour of breath is at once meditative, meticulous, habitual, and laborious. With 'un-language' as my touchstone, I see movement as an overarching act that encapsulates sound, breath, and mobility as antecedents of language, the language of bodies produced through exertion and endurance.

The third one, a sudden sharpness of a bird flying through a still breeze on my Instagram post when I departed Melbourne, or uncannily perched on a ledge, has the quality of an omen. I see signs and patterns and the presence of birds fluttering in, with and away from life, is a portent.

These three bird videos are stated as stillborn, dead, and hidden, but also a melancholic reflection on the generic nature of hidden violence and absence. The birds are a metaphor for precarious living in a world fraught with violence, and the final moment of flight, as I posted on my Instagram, is a moment of imagined release from this hold. —[O]