Helen Cammock: ‘The role of language is endless’

Helen Cammock. Photo: Sebastiano Luciano.

Helen Cammock. Photo: Sebastiano Luciano.

When I speak with British-born artist Helen Cammock, she is packing up her home in Brighton, a city on the southeast coast of the U.K. where she has been based since 1989.

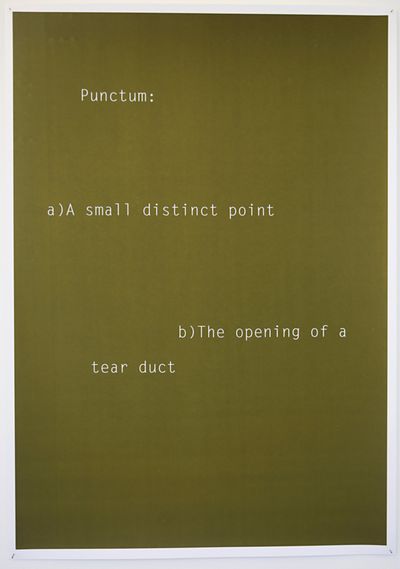

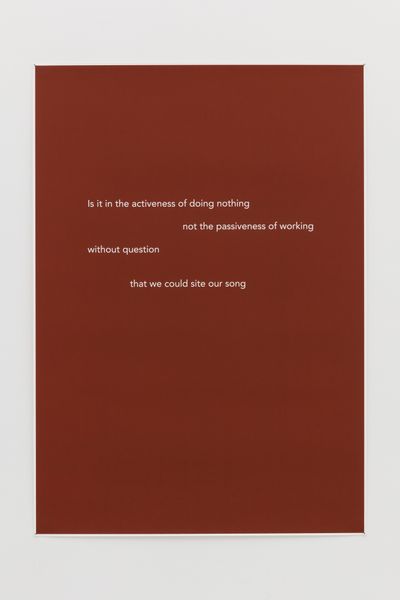

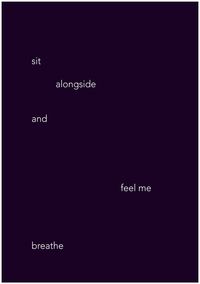

In an upcoming commission by media company Buildhollywood, curated by Zarina Rossheart, Cammock responds directly to the city's identity as a hedonistic seaside resort and radical political enclave through 16 public billboards containing fragments of poetic text on expanses of colour.

On view between 3 and 6 August 2023, the commission is part of a U.K.-wide project titled All About Love, drawing from the same name as the book by cultural critic, feminist theorist, and author bell hooks, which expands the definition of love beyond its romantic connotations to community care and compassion and how it can pave the way for social justice.

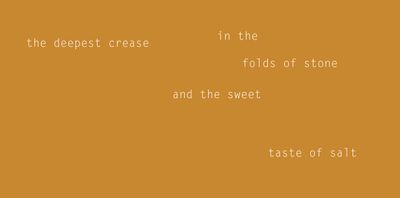

The commission was originally intended to be shown alongside The deepest crease in the fold of stone and the sweet taste of salt, a public work shown on the façade of Brighton CCA, the University of Brighton's contemporary gallery, before the institution was called to close in May, with the University citing rising energy costs and inflation as the cause.

To discuss the importance of nurturing local art scenes such as Brighton's through arts education, Cammock will join Brighton CCA's former director, Ben Roberts, as well as Lucy Day, the executive director of Phoenix Art Space, in a panel discussion held at the local studio and exhibition complex on 2 August 2023, moderated by The Art Newspaper journalist Anny Shaw.

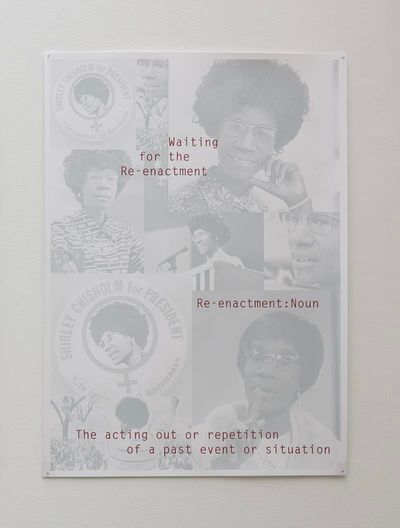

Working across video, text, and photography, Cammock splices fragments from historical and literary texts, shifting between fact and fiction; personal and collective experience to uncover modes of resistance and resilience within legacies of oppression.

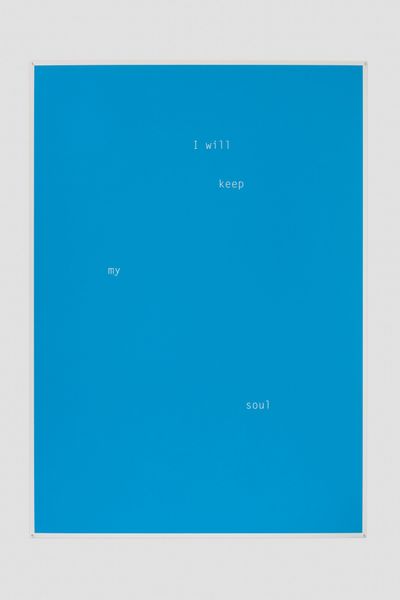

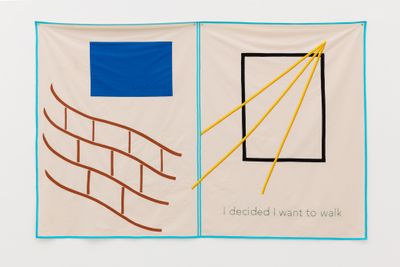

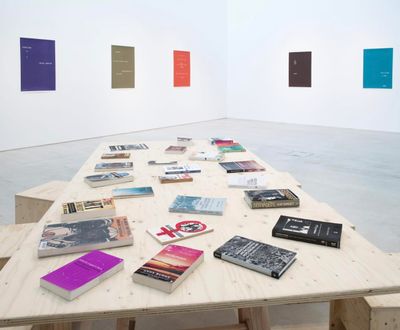

It is a regenerative practice that makes use of open-endedness as a tool for reconfiguration, unveiling the different narratives and perspectives that form historical events. One example of this approach is the artist's current exhibition, I Will Keep My Soul, at Art + Practice in Los Angeles (11 February–5 August 2023), in which poetic phrases distil Cammock's observations and research into the history and community of New Orleans in the United States.

Printed text works line the walls, containing phrases such as 'To learn to / dance / with fireflies / first / accept the / dark', while literary materials are available to read in the space, connecting the city's past and present.

These include journalist Ronnie Greene's 2015 book Shots on the Bridge, detailing the murder of Black civilians by police after Hurricane Katrina made landfall in 2005, as well as Kim Lacy Rogers' documentation of accounts made by leaders of the local civil rights movement, Righteous Lives: Narratives of the New Orleans Civil Rights Movement (1993).

Being in dialogue with different voices is key to Cammock's practice, having worked in the social care context for ten years in children's services prior to becoming an artist. Her Turner Prize-winning film The Long Note (2018) is one such example, gathering the voices of women who partook in the civil rights movement in Derry, Northern Ireland, in 1968.

Following British gallery Towner Eastbourne's recent acquisition of The Long Note performance, Cammock performed live at the institution on 27 May 2023, expanding on the theme of resistance to reflect on global dissent in 1968. It preceded a new commission by the artist to be unveiled in the Eastbourne Winter Garden in autumn 2023, co-commissioned by Eastbourne ALIVE and Artists' Research Centre.

With song and spoken word, Cammock's performance quoted individuals ranging from Nina Simone to Colette Bryce and Malcolm X to Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, drawing parallels between the housing crisis in Derry, which spurred the local civil rights movement in Northern Ireland, and that of the U.S.

In the following interview, Cammock elaborates on the importance of bringing a range of voices into her work, the formal elements used to make this happen, and how she is tapping into the unique context of Brighton for her upcoming work.

TMText is a core component of your practice. What inspired the title of your commission, The deepest crease in the fold of stone and the sweet taste of salt, which was intended to be shown on Brighton CCA's façade before it was called to close?

HCI wanted to express this idea of the fold as a liminal space, a way to make sense of one's inner world and its inextricable relation to the different folds occurring within outer worlds—such as communities. Thinking about what love means in terms of community and politics, you arrive at questions around care: who is seen and gets cared for, and who doesn't.

I believe we never stop learning if we are open to others.

There is a relationship between inner and outer care, and when one is missing, then you have a problem. In a poetic way, I wanted to ask questions of people who read the text, which is trying to probe and provoke, asking how they feel and see the world.

TMThe sweet taste of salt taps so beautifully into Brighton's identity as a hedonistic seaside resort. What other aspects of its identity are you reflecting on in the upcoming billboard commission by Buildhollywood?

HCI have such a love for this city, which is the sweet taste of salt. It can present different possibilities and sensations across winter and summer or depending on who you are and how you are inhabiting its different energies.

There's something about stick of rock [hard-boiled candy] and stag and hen-dos that is really hedonistic and full on. The flip side of that is the real salt of the place, which is sweet because its politics, on many levels, are supportive and caring, and in the political climate that we live in, appear to contain some kind of radicalism.

If we think about where Brighton is in East Sussex, and in the southeast context outside of London, it's on its own; it's an island. Of course, we know that it's by the sea and edges the water, but it feels to me that it's edged by politics and values that through its resistance keep it afloat. So politically—big and small 'p'—it activates something very special and specific in the southeast.

TMWhat has Brighton meant for you personally?

HCI came to Brighton to go to university as a young lesbian in 1989; I knew that parts of the country weren't going to feel safe for me, but Brighton was a place where I could grow, be happy, and experiment. That sense of safety held me here.

Demographically, Brighton is quite a white city, but it's changed over the years, and even with its whiteness, there is an engagement with people who are seen to be other. That doesn't make it perfect, but it makes it a place where all aspects of who I am can be seen. I wanted to focus on why that's important and what it means to individuals and communities.

TMDialogue is central to your practice, which amplifies voices in varying contexts. What has your work with different individuals in social care meant for this project, and practice more broadly?

HCThe task was really to make a work with and for Brighton. I'm not really into making slogans, so it is more a questioning, and asking for reflection from audiences. I am asking them to reflect on patience, the ways we generate ideas, why thought and active thinking are valuable, and how creative processes are about caring for the social context around us.

My practice more generally includes reflections about myself, but I am who I am because of people that I've known and worked with and the histories I research. The way I work with others is very much influenced by having worked alongside many different people in different situations.

Years ago, I co-ran a Brighton-wide project around domestic violence for women and children. I ran different group work programmes and was a chair of a foster panel until about five years ago, so I've kept working with people because it matters to me; it's important and part of who I am. I believe we never stop learning if we are open to others.

I hope that those people will continue to be part of how I think, and that they're considered in what's being said, in terms of bringing forth the value of different experiences—it's an internal process.

TMYou have a specific approach to dialogue; in The Long Note, for instance, individuals recount their experiences of Derry's civil rights movement, whereas your voiceover is more poetic and open-ended when it comes in. Why?

HCIt felt important in The Long Note because it's not my experience, so my voice needed to be used to hold up the voices of those who are speaking about theirs as a way of threading together different stories, sites, or forms of storytelling in the film.

TMIn one segment of the film, a hand hovers over the music sheet and recorder. Could you speak about its significance and relation to your wider practice?

HCI wanted to create breathing space. The segment offers stillness but it also acknowledges my process and role as a writer of the narrative.

The way that stories are told is very important, and song is a massive part of that. In Derry, I wrote a song with a group of young and adult women, and when it was performed, it was almost a call and response. It was a beautiful experience.

It was about young women saying we hear what you have given us, and now it's our time to move things forward; we'll take what you've given us and run with it in our hands. I wrote the melody on a recorder, took it to the women, and that's how we wrote the song together.

TMYou've been singing and making music for a long time, but only started taking singing lessons during your residency in Italy. Could you speak about the experience?

HCThat was the hardest thing I've ever done. I have sung solo in folk clubs and also with bands, but nothing professional. I only gained the confidence from a conversation with artist Anne Tallentire, who asked me why I hadn't sung in my films.

She runs an evening project called hmn in London with writer Chris Fite-Wassilak, where they invite artists to come and try something new, so it's about taking risks in a space with other artists who can give you feedback.

So I wrote my first performance called Song and Shiver (2016) and performed it at Shoreditch Library on Hoxton Street in London. The acoustics weren't great, but it went very well, and I thought... I can do this—I can use my song and voice as an artist.

TMDid you relate to your own voice differently after doing lessons?

HCYes. When I was a singer, I felt that I couldn't hit high notes because I've got this soulful, low bluesy voice. So I worked with a singer in Italy and we did a vocal test with piano to see how many octaves I could sing. She told me that I'm a contralto, but could also sing to soprano if I learned to use my body differently. She said I was just too frightened to do it.

For the project Che Si Può Faré (2019), I chose to perform a pre-opera lament. It was complex and challenging and actually a frightening experience, but having performed it once in Italy and twice in London, and singing it in Italian too, I feel like it has freed me up to do anything with my voice.

It doesn't have to be perfect, it just has to have intent, emotion, and raw honesty. It's about interpretation and transformation—just like any art form.

TMHow did that shift how you work with different voices?

HCIn 2011, I became conscious of this idea that I call the audible fingerprint, which we all have. It's the idea that certain words will contain different meaning when spoken by one person to the next. The idea that meaning shifts depending on our subject position, the experiences we've had, and who we represent in the world in relation to others. It's all relational.

Then there are different registers of the voice—spoken, shouting, sung, political, poetic, philosophical, or silenced—which is where the idea of song comes in. These different registers and how and when we employ them reflect the social structures in which we live, but they're also about our internal, emotional world.

Everyone tells stories differently. Some people with children are great readers of bedtime stories, others really struggle with it—and this is usually not about how literate you are. Some people are beautiful singers, others express something viscerally when they sing, but technically are not great. These different registers of the voice offer a foundation for my performances and films.

My text work is quite different from my films, where I quite often have a voiceover that's clearly my voice. When I have a fabric banner or print text work, it plays with sound differently. Through reading the text your internal voice is activated, which again shifts the meaning of what's being read. It may also change a statement to a question and vice versa.

For example, in my L.A. show I Will Keep My Soul at Art + Practice, the text excerpt from a print work—'To learn to / dance / with fireflies / first / accept the / dark'—means one thing to me, but might mean something completely different to you. There are pointers and context to my intent but our differing experiences, politics, and value systems may change what is being understood.

You are reading it in your own voice, so there's something about being in dialogue with yourself, which brings us back to this idea of the fold—folds upon folds upon folds of identity and experience.

TMBass Notes and SiteLines, your 2022 exhibition at Serpentine Galleries in London investigated resilience and resistance by connecting with those working in the social care system as well as those receiving care.

In the U.K., the government has framed resilience as a quality necessitated to thrive in the 21st-century workforce, pushing for workers to re-skill and possess a certain 'flexibility', where state support is limited or difficult to access. How can a return to the core elements of existence—the body and voice—reframe the dialogue around resilience?

HCI realised quite late how significant the voice is in terms of resistance, resilience, and the links between them. Often, we hold everything in our body and try to exhale everything through our voice, and for some people it's much easier than it is for others. Some people have more time and space for breath... Some people have better quality air... We all have different risks at play—with more to lose or gain in every encounter.

I think there's a lack of understanding of the importance of care in terms of being enabled, meaning being able to speak for ourselves in every situation. For the women working with Pause [organisation supporting women affected by the social care system], the idea that their voices would ever be heard is sometimes quite beyond their comprehension.

There's something empowering about being able to say no, I can do this, or that I will fight you, or for this, because it is important to me. We speak every time we do anything, through our bodies, gestures, behaviour—even voting. But for the voice to come out, often we need extra care.

I believe our cyclical histories are written and re-written by us in every moment that we speak, or don't speak.

It's quite easy to show your disdain or distress through the body—we might become ill, ignore people, decide that people don't need to be looked at, seen, or heard, but there's something really demanding about speaking up for yourself or for others.

The political moment we are in is terrifying and makes me angry. There are people in government who—I can only imagine—have opportunity and advantage but perhaps lack care on an emotional level. Something is missing—a disconnect, a dislocation. When this happens it appears people find it difficult to be empathetic and therefore are unable to acknowledge what it means to be voiceless, unheard, or unseen.

TMWhen people aren't equipped with the tools to understand their inner voices, it becomes difficult to empathise with others.

HCThis country, like many others, is built on inequality. That's how as a society we consider what is successful and who is thriving: to have certain people subjugated and others benefitting from their labour or hardship hasn't changed for many centuries.

It's an intersectional relational understanding and crosses geographies and histories. There are so many conscious and subconscious forms of messaging and impulse reinforcement that to feel that you can freely make your own decisions and express them—and have them heard—is a position of extreme privilege. If you have this then it's a responsibility to consider how you use it. It's a question of unpicking and acknowledging, learning, hearing, and activating.

For that to happen, we must have people in charge of situations who are in touch with themselves. They may have also experienced situations of discomfort, isolation, or marginalisation in some ways, and if they haven't, to be insightful enough to listen to people who have instead of being threatened and frightened of them. Ultimately, I believe certain types of fear that are non-violent or non-life threatening can actually build strength, learning, and respect for yourself and others.

The younger generation are shouting about it now in terms of the damage to the planet. There is a sense of empathetic care, and this must extend across everything that we do, imagine, and believe in.

As an artist, it's important for me, but also for schools and politicians. I suppose I believe there is a way of telling stories that can enable people to care but we have a long way to go for these understandings, feelings, and actions to be sustained.

TMIn your work, formal structures, such as architecture or the line, often ground poetic elements. How do you use form as a device?

HCForm is probably the most significant element in my work. In my films, for instance, I take a non-cinematic approach where action comes in and out of the frame rather than following it.

There's something about being stable and quiet, which allows for something to happen between voice and image and text and colour. I have very layered sound that you might sometimes miss because it rumbles away subliminally underneath the imagery. Sometimes what you see and hear make sense and other times they run across and against each other.

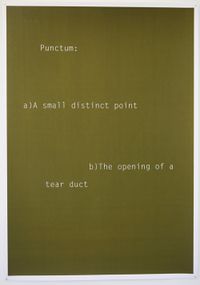

It's a similar strategy in print work, which is generally a broken line of text floating in a colour background. For me, this is about form, because different dimensions take shape through juxtaposition, gaps, shape, length, and so on. It's saying words have different meanings that could change in various contexts and combinations. The form is conceptual.

I also film a lot of places where people live and where people are absent to consider what's happening within a constructed space. Most landscapes we inhabit, whether they're urban, are constructed, so there's something about human presence even when the absence is significant and might be placed alongside something that is challenging within the voiceover.

All these formal elements are strategies. Another is interweaving texts or stories to reveal, manipulate, or generate ideas intentionally—to try to ask questions about the power of language in its control of us, but also its role in care. The role of language is endless.

Ultimately, in my work, it's not about literacy but a wider sense of language: storytelling, sound-making, and the possibilities of telling stories in non-verbal forms. I believe our cyclical histories are written and re-written by us in every moment that we speak, or don't speak, and recognising the power and disempowerment of our own voices is critical in understanding how we shape what is around us. —[O]