Travel an hour east of Zurich and you'll hit St. Gallen, a small city in northeastern Switzerland hosting Camille Henrot's latest exhibition, Sweet Days of Discipline (10 June–5 November 2023).

The exhibition takes place at the LOK, a former locomotive garage and Kunstmuseum St. Gallen's second venue. There, Henrot has mounted a large-scale installation of over 30 works on themes of alienation and coming of age for her debut solo show in Switzerland.

Henrot sat down with Ocula Advisor Rory Mitchell to speak about her latest works, her unusual approach to reading, and her admiration for Austrian artist Maria Lassnig.

Your show is titled Sweet Days of Discipline. Could you talk about how it embodies your approach to this exhibition?

When I saw the nature of the space, its high ceilings and streams of sunlight, I knew I wanted the exhibition to be predominantly sculpture. The building's name, Lokremise, translates in Swiss-German as the storage of locomotives. Historically, this is where all tracks converged and you can still see them running through the space today.

Timing and schedule are not only specific to this place, but to Switzerland—a country that has a reputation for being extremely conscious of timing, scheduling, and planning ahead. I wanted to build off this and relate it to the way we, as children, learn the discipline of adjusting to time. But also how as adults, we have to adjust to the codes of society.

I read Sweet Days of Discipline [1991] by Swiss author Fleur Jaeggy. Very few people know about her in Switzerland, but the book is based in a school in St. Gallen. Both my exhibition and her book relate to the violence of social codes and the adjustment necessary for an individual to fit into society.

Has your work always been influenced by literature?

Yes, I think that's the common thread. There was a moment when I was more inspired by essays, philosophy, and social science, but literature has always been there.

Both the narrative and the sources of the soundtrack of my films, Grosse Fatigue (2013) for example, are from numerous origin stories. Some are collected from myths, and others are from science comic books or children's books about physics.

I collect words the way another would collect stones on the beach. Like a bird, I'll steal two or three words from one nest, and two or three from another, and then bring them together.

While I love reading, and sometimes write, I am not a bibliophile. I read in a very messy, disorderly manner. I'll have 20 books on my table and be reading 15 at the same time, sometimes in different languages.

I love one of your quotes: 'As an artist, I have the freedom to browse through ideas with the curiosity of an amateur. I'm allowed to have an irrational approach to knowledge.' That seems to tie into how you read.

Yes, I feel like I've got quite a childish approach to reading. I like to play lost and found with books and believe in them like religious figures. I would open a book and find a sentence that would miraculously give me a direction for the day, or the title for a work.

It's more of an emotional, superstitious relationship to the book as an object. I don't read them on a Kindle, or listen to podcasts. I like the book as an object that opens and closes.

Some of your installations feature an array of found objects. Have you always been a collector of things?

Growing up, I had a huge collection of postcards that I organised by artist and period in huge binders. So this craze of collecting was very much there in my early childhood.

Today, the activity of collecting and gathering is very much what I do. My new paintings from the series 'Dos and Don'ts' (2021–ongoing) about etiquette are like collages. The thread between the different media I use can be seen as a process of gathering, editing, and pasting together.

Do you make paintings and drawings every day?

Not every day, as there's a lot of preparation. It's a bit like a sports event. I need to get prepared and train myself. I make my own paint, so choosing the right consistency and colour can take a while. But once I'm ready, I can produce several paintings in a single day.

I work a bit like a bird in that I have a seasonal practice. During the six months of winter, I'm mostly drawing and painting, and during spring and summer, I'm taking advantage of the good weather by working on sculpture or filming.

I read that you were influenced by Maria Lassnig's painting.

I had images of Maria Lassnig's paintings on my reference board but didn't have her name written on it. I thought she was a young painter and then researched and found out her story. I was amazed at how close I felt to the spirit of her paintings.

In 2019, Frieze magazine asked me to pay homage to one artist. I decided on Lassnig and started to train myself to imitate her paintings.

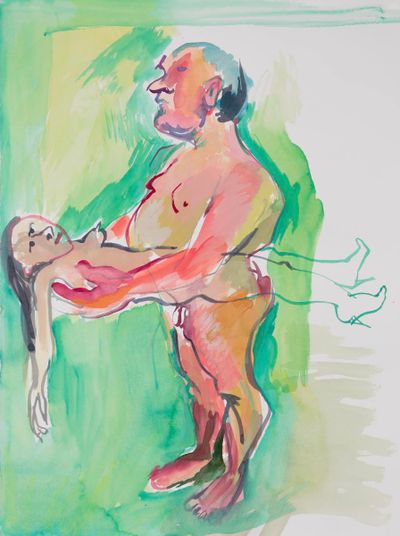

For a long time, I was feeling a bit cautious with painting because of the heaviness of its history dominated by male figures. The process is quite long, which also felt counterintuitive compared to drawing or working with ink. However, I related to her use of fresh, acidic colours, her line, and her cartoony way of painting.

I am drawn to her paintings' themes—feelings of rage and powerlessness, but also seduction. Her painting, Sleeping with a tiger (1975) almost has this idea of domesticating your trauma and pain. I felt this struggle often in my own work, identifying with both the victim and the aggressor, and feeling a certain ambivalence with representations of violence.

You were also inspired by Picasso's line.

He also has an amazing line—one of the best lines in the history of art. Growing up in France, there was constantly a Picasso show somewhere. I always had mixed feelings because he was a bit too much of an authoritative figure.

However, I always found his paintings quite funny. While he may have been a horrible, arrogant man, the paintings themselves are not arrogant at all. They have so much humour and self-deprecation.

I was very much surrounded by art history at home. My mother was an artist, so as a child, I went to see many museum shows. We would go to museums and draw together—she was very good at drawing and also had a great line.

Can you tell us about the works in your exhibition at St. Gallen?

The show is predominantly sculpture and it's the first time I've worked with so many materials and experimental techniques. I wanted to start thinking about materials that were a bit less expensive and less carbon-consuming—ones that are less consequential than bronze. In that search, I became very interested in techniques using wires, aluminium sheeting, steel wool and concrete.

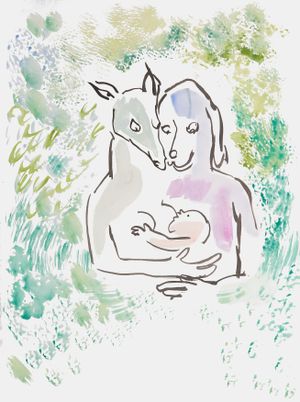

At the entrance of the exhibition, there's a group of dogs attached together to the wall by their leashes. It's unclear whether they are guarding the show or have been left there to wait. It begs the question: who's guarding whom?

Dogs in and of themselves are a very direct representation of dependency and the ambivalence between caregiver and receiver. Dogs come in all shapes and sizes and levels of grooming. The dogs in the show, which are made with a variety of different techniques, became an illustration of the many diverse forms of care and attachment.

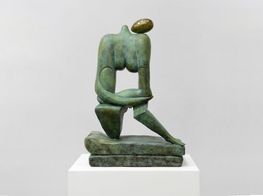

There's also a number of bronzes in the show—there's something really magical about the material. It's so liquid and captures every detail. No other material renders the passage of age and time on the body better than bronze.

I became interested in the body posture of someone guarding, attending to others, and waiting for their duty to end. There's often an exhaustion and a tenderness to it, too. Most of the figures are female, as it's mostly women who do this kind of job. I think we project a sort of expectation of comfort on the female body.

In art history, sculpture has inherently played the role of a substitute for the mother body. A bit like divinities that are protected, sculptures protect and are made to protect.

At the British Museum, for example, you see the parts people have been touching, and it's always a part that is very round—the breasts, belly, and buttocks. That really triggered me to work with this idea of the sculpture as a substitute.

The figure of the nanny, or babysitter, is also important in the show because she's a substitute for the parent. Everybody is being cared for by somebody else, somebody with whom they have a distant relationship, which is also the story of the novel, Sweet Days of Discipline. —[O]

Main image: Exhibition view: Camille Henrot, Sweet Days of Discipline, LOK Kunstmuseum, St. Gallen (10 June–5 November 2023). © Camille Henrot and ADAGP, Paris (2023). Courtesy Mennour, Paris and Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong/London/New York/Los Angeles/Zurich. Photo: Sebastian Stadler.

Selected Artworks

25 x 60 x 15 cm Hauser & Wirth

Request Price & Availability

76.2 x 55.9 cm Hauser & Wirth

Request Price & Availability

Hauser & Wirth

Request Price & Availability