Filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin on the Sacredness of Listening

In partnership with Artspace Aotearoa

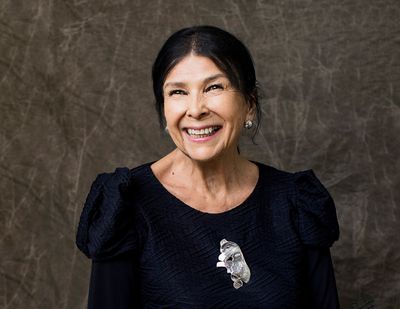

Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: Julie Artacho.

Alanis Obomsawin. Photo: Julie Artacho.

For Canadian filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin, listening is a sacred act that connects her to the lives and stories of people. Her astute eye and ear translate an empowered, sensitive form of storytelling, one that centres a relational process and imbues its manifestations with integrity, generosity, and intent.

Obomsawin is a member of the Abenaki Nation. She was born in 1932 in Lebanon, New Hampshire on Abenaki territory and at the age of six months her mother took her to Odanak, Quebec, where both her parents were born. Her career was initially as a singer-songwriter, performing across Canada, the U.S., and Europe. But when she discovered filmmaking and made her first film, Christmas at Moose Factory—a short documentary composed of drawings and stories told by young Cree children at a residential school in Ontario—in 1971, it became clear to her that she could use the documentary genre as an educational tool to tell the true stories of Indigenous Canadian people.

Obomsawin is a director and producer at the National Film Board of Canada, where she has worked since 1967. Her films document Indigenous issues, events, and practices, from the animal stories told to children to land disputes.

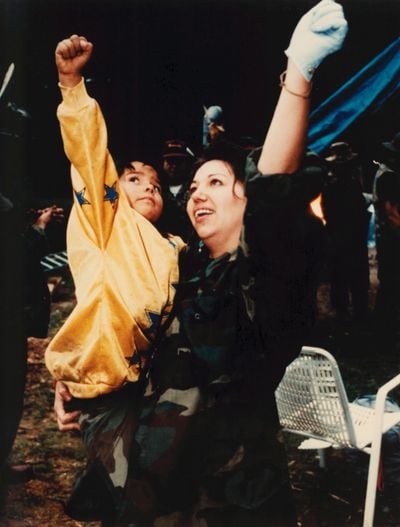

Her groundbreaking Incident at Restigouche (1984) takes a behind-the-scenes look at Quebec police raids on a Mi'kmaq reserve, while her landmark documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) details the 1990 Kanien'kéhaka (Mohawk) uprising (also known as the Oka Crisis or the Kanehsatake Resistance) in Kanehsatake near Oka, a small village in Quebec. The resistance, which lasted 78 days, responded to a nine-hole expansion to an existing golf course on Kanien'kéhaka lands. Obomsawin's film became the first documentary to win Best Canadian Feature at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), and has since received 17 other Canadian and international awards.

Obomsawin frequently narrates her own films, strengthening their potent sense of intimacy and immediacy with a calm and measured voice. The voice becomes a channel through which to convey history and feeling; as Obomsawin describes in this interview, when listening to a person tell their story, 'you feel everything in their voice.'

Her upcoming films, Wabano: The Light of the Day and The Green Horse [working title], will be her 56th and 57th in a nearly six-decade-long career devoted to chronicling the lives and concerns of First Nations people. Earlier this year Obomsawin was the first woman filmmaker to receive the Edward MacDowell Medal in its 63-year history, a U.S. award that recognises individuals who have made significant cultural contributions. In 2021, TIFF presented Obomsawin with the Jeff Skoll Award in Impact Media, which recognises leadership and the creation of a union between social impact in cinema.

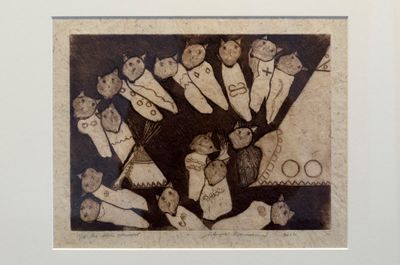

Obomsawin, who has lived in Tio'tia:ke (Montreal) since the late 1950s, flew to Aotearoa New Zealand in late August at the invitation of Ruth Buchanan, director of Artspace Aotearoa, in advance of her solo exhibition there. To move between: Healing and Resistance (2 September–4 November 2023) includes four of Obomsawin's films, the earliest of which is Poundmaker's Lodge: A Healing Place (1987), a documentary on an addiction treatment centre in St. Albert, Alberta for Indigenous people, and the most recent being We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), which traces a nine-year legal battle between the federal government and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations. Presented alongside the films are three etchings by the artist, depicting various dreamlike scenes of sacred animals, and tables of archival materials including posters, newspaper clippings, and illustrations.

This is Obomsawin's third visit to New Zealand, during which she celebrated her 91st birthday coinciding with the once-in-100-year blue super moon. While in Auckland, she visited children at a local school and hosted a workshop for emerging filmmakers. Both form a part of the rituals she likes to practise when visiting a place as a way of connecting with the local community. Public talks are another. On 2 September, Obomsawin spoke with New Zealand-born Samoan photographer Edith Amituanai to an intimate crowd at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, dressed head-to-toe in scarlet, 'to honour all the [Indigenous] women who have disappeared, or been killed,' she said.

In the following conversation with Amituanai, based on the talk at Auckland Art Gallery, Obomsawin discusses formative moments across her career and shares stories about the making of films including Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance and Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986). With fondness she recalls her connection to the celebrated late Māori filmmaker Merata Mita, whose documentary Patu! (1983) on the 1981 Springbok tour in New Zealand marked a watershed moment in the history of Indigenous filmmaking in Aotearoa, and reflects on memorable moments throughout her career, radiating optimism all the while.

EAI wondered if we could start with your process of filmmaking. I've been listening to some things about the practice of sacred listening and I wondered if you could talk about the process of how you tell stories.

AOWhen I discovered filmmaking, I realised how powerful it was to have the image to see and hear people telling their own stories. That's what I was interested in, mainly because the educational system that we had for many generations had people teaching the history of our country with lots of lies and stories designed to create hate for our people.

Every time I make a film, I'm always thinking about education . . . Our history and teaching has a lot of power.

In my time we were not allowed to speak our language. They used to say to me, 'your language is Satan's language', and you got to believe that. As a child, I figured the children were not born hating me. They didn't know me. I figured it was because of what they heard about my people, who we are. I thought if they heard a different story, they would not feel this way. That's where I got the idea. I am a storyteller and I have to get into the classroom—and not just me, but the people where I come from. It didn't happen overnight, but that's how it started.

Every time I make a film, I'm always thinking about education. It is important because this is where the power is, that's how you get people to know what the true story is of our people. Our history and teaching has a lot of power.

The books that were so racist and damaging to the lives of our people are out of the classroom now, they don't exist anymore. As a result, a lot of our own people have written books about their history, about where they come from. We now have our history as part of the educational system in a lot of places. Now the language is respected and taught even at university level, and certainly locally to the different nations' villages. Even ten years ago I could not have spoken the way I speak now. The [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] has been very helpful. People are more open to hear what the truth is. People want to know what the real stories are and are starting to recognise how important and beautiful they are. It's only enriching.

Our young people can do anything now. They can take part in any discipline that they feel they wish to be and there is help, respect, encouragement. As I travel, I see that Canada is at the front in terms of paying attention to Indigenous people and changing terrible laws. There are still some that remain, but there's a lot of change, a lot of love from Canadians who wish to see justice for our people. I am so lucky to still be living and see the difference in our country, how possible everything is for our young people.

EAI saw an interview where you talked about partying with Merata Mita. I wondered if you could share your birthday story?

AOMerata was very important to me. We met in 1984 at the Guelph Film Festival in Canada. We conversed and it was like I knew her a thousand years ago. One time, I was having a big party for about 150 people—I think it must have been when I turned 85—and Merata was in Montreal. It was summertime. It was three o'clock in the morning and there were still perhaps 15 people, all sitting on the floor. We were singing, some of them were playing instruments and it was very nice.

The police came because we were too noisy. I said, 'I'm very sorry,' and closed the door and we went on until five. Merata had to take a plane in the morning and I had to go to Ottawa. I said to her, maybe we should lie down for a little bit. I woke up at ten o'clock and said, 'Oh my god'. I rushed to Merata's room and she was gone. But she didn't miss her flight. I was late to Ottawa and you would've never known I had such a great time the night before. It's such a beautiful souvenir.

When I came [to Aotearoa the last time], Merata had passed away and it was terrible. She had told someone to change the date of the Women's Film Festival 'because Alanis is coming and she hates winter, so we have to have it in the summer.' So the festival was in December. Was I ever happy to leave Montreal, it was freezing like hell. But she had gone.

Some friends took me to her grave by the sea. It's very beautiful there—there's the big, big tree with the red flowers. That's where she came from. Merata and I used to sometimes drink a little whisky together, so I had a tiny little bottle of whisky. I had a teaspoon full of it and one teaspoon for Merata. I was talking to her the whole time and I knew she could hear me. That's my friendship for New Zealand.

EAWhen making Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, I have heard you talk about how you were going to run out of tape, and you had to save what you could document. I wondered how you knew what to film—how could you decide, knowing there were so many things to film?

AOOnce I managed to go into the village [Oka, Quebec], I knew I could not come out again. If I did I couldn't get back in. I stayed there for 78 days. I had two crew, one at night and one during the day. The Warriors retreated to the treatment centre which was behind barricades. I said we had to go behind, but they only allowed two people. So I took the sound recorder from the sound man. I was doing the sound and I had one cameraman. I think two days later, the cameraman said, 'there's going to be a terrible thing here. I'm leaving.'

I was allowed to change [the crew] so I got an assistant cameraman. He said, 'Oh my god, this is awful, I'm scared.' He stayed maybe three days, then I was not allowed to exchange [crew] anymore. I was on my own with just the sound equipment. It was very scary. You never knew what would happen next. If there was one shot from the army or the Warriors, we were finished. Finally one of my cameramen was allowed to bring me things like clothes or a blanket. He hid a video camera at the bottom; we were shooting on 16 mm. They were calling us dinosaurs because we were the only ones shooting 16 mm.

Now I had a video camera and the Nagra, which is a professional recorder, and I was doing interviews. There were all kinds of things happening, terrible stuff going on. A lot of the film was shot by a professional cameraman who was working for me. When I'm shooting at the end with the video camera, the quality is less but it has become important. This is the only proof that I was there filming. It was very difficult—you just never knew what would happen.

For around a couple of weeks we had the army in front. As I came out with other photographers, every day I would hear a soldier say, 'now here's the squaw'. One day I heard a soldier saying to another soldier, 'Hey, there's your squaw'.

Squaw is an Algonquin word. Algonquin represents many different nations who have a certain similarity in the language and in some traditions. And we are the Algonquin-speaking Wabanaki or Abenaki people. We have the word squaw, which is a beautiful word. It means women. But in Canada and in the States, the word squaw has been interpreted by white people to mean: 'You're nothing. You're a whore and I'm going to do it to you and then I might kill you.'

So many women have disappeared. Some were killed and some were never found. It's a horrifying history, which is less now, but it is still happening. I knew that if they called me squaw, it meant I was in danger. Anything could happen. I was sleeping outside on the earth on top of garbage bags. You didn't sleep very well because you were always worried. But I'm glad I did it and stayed until the end. I knew they were coming out, and I came out one day before because I wanted to save all my material, otherwise it would've been confiscated. It's not an experience I wish on anybody, but it was very important to document it ourselves.

EAIt sounds like it is very important for you to document these stories. I was going to ask if you think that you are brave, but I can see that you are driven by the importance of documenting these important events.

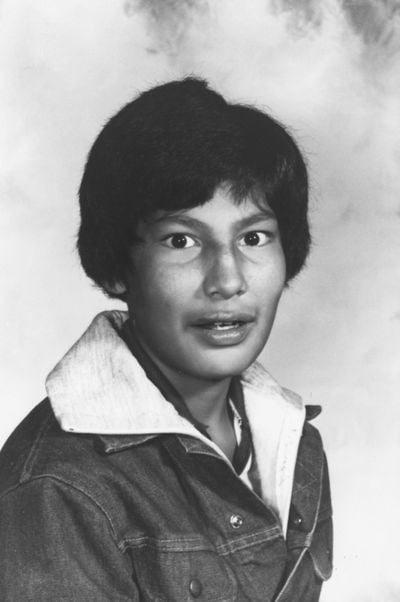

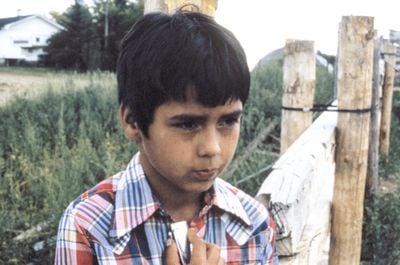

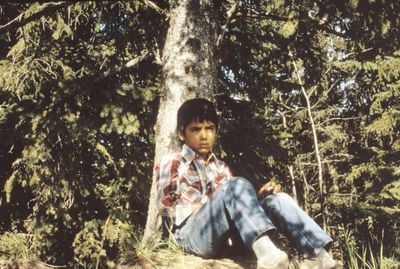

The first film of yours I saw was Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986). I was a youth worker in training and it was shown to us in the classroom while we trained to work with young people mostly in hard, hard situations. We were floored by the story because it is unfortunately one that we know here, but I was taken aback by the bravery of your storytelling. How do you keep pushing on to tell these stories?

AOI don't think of it that way. I was working on another film in Edmonton and I saw this woman being interviewed on television about this young Métis man, Richard Cardinal, who had hung himself on her land. I was very disturbed by it. I decided to go and see her because I didn't want her to regret having taken him in. He was their foster child and had been in 28 different homes over his life. I went to explain our situation and foster children and people on the street and what it means. I didn't want them to feel that they should have never gotten into this trouble. I got to know them a little bit, they were gentlemen farmers.

It was very late. I was stationed in Edmonton and they were in Sangudo, which is maybe an hour or so away. They said, 'why don't you sleep here instead of driving back?' I said I would love to and I want to sleep in Richard's room. So they took me to the room and I slept there. I was talking to Richard and I asked him to tell me how he felt. I had this terrible dream that I was in a garage where they fix cars and a car is up there, and I was lying down there and this car was coming down on me. To me that was the answer.

There was an investigation and people were asking for an inquiry, but the government refused. The journalists of the town were incredible, there were many articles. Finally they did the inquiry and I attended. Meanwhile, I decided to make a film on Richard and started doing interviews. I thought, oh boy, it is not going to be easy. Anyway, I made the film. All these things are difficult in many ways. You have to decide for yourself, you are not why you're doing this. I certainly didn't want any children to ever go through what I went through. So I work hard to make sure that this doesn't happen.

There was a picture of him, Richard Cardinal, hanging on the tree, which was published in the newspaper. People were complaining. A lot of people said, oh, don't put that picture in. It's going to be terrible. Who made this child commit suicide? Well, those people who made it had to look at it and face it. That's the way I felt.

The couple where Richard was, they had gone out and when they came back, they couldn't find him. And all of a sudden they saw him hanging in a tree on their land. They called the police and they said it took four hours before they came. All this time Richard is hanging there. Finally the police came. But they never went back or questioned the couple, and [the foster parents] couldn't understand it. The foster father went and took a picture, 'just in case,' he said. One month, two months went by, but the police never came back to ask, 'Why do you think Richard committed suicide? Were there problems?'

There was just another Indian that was dead and it didn't count. So [the foster father] sent the picture to the newspaper and to the Métis Association, and it appeared and made a big shot. That's how this woman was on TV, that's how I went [to Sangudo]. Then there was so much criticism against the system—moving the children from the reserve like they did with a lot of them, sending them to residential schools, foster homes—sometimes far away and sometimes getting them adopted without their parents knowing.

[The film] helped to change the law in Edmonton because up until then, we had reservations in Canada, and if something was wrong with the family or a child, or if there was a need for money for children with special needs or things like that, there was a lot of injustice, like no financial help for the parents. But if you removed the child and put them in another family, they would pay that family to take care of that child.

They made a new law, that you could not remove a child and place them in a foreign place. You had to look first on the reserve, for a relative who would take in the child. If the child must leave the reserve and go into the city, you have to find a house of Indigenous people. It was the first time they did that. In the past there were a lot of our people who wanted to take children in, but they never qualified. The system made it very difficult. But [it changed]—instead of removing children and putting them in institutions, they had to go to an Indigenous family and that was much better. This film [helped] that because it was so embarrassing for the system. It goes to tell you how powerful documentary filmmaking is.

EAI wanted to talk about your skill in making these films that is beyond or more than filmmaking. You are also a social worker in that you went to see that family to make sure that they did not regret their time with Richard. I wondered if you could talk about your different roles and how they may aid your filmmaking, as a musician, an educator, a storyteller. Your films are incredible because you have a range of skills and you're incredibly sensitive and smart. I wondered if you could talk about some of those skills?

AOWhen you're filming situations like in Kanehsatake, they call that guerrilla filmmaking because you're running around like crazy, filming things as they happened. You don't want to miss anything. Usually if I decide to make a documentary on a person or a community, I spend a lot of time listening to people. I go along with a tape recorder and I interview them privately, alone. Sometimes I have to go back until I understand what the story is. I don't come with a crew without knowing. For me, the word is sacred—very sacred—because when an individual is alone with you and they trust and feel at ease, they say things about themselves, their life, that are so moving and you feel everything in their voice.

By listening to how people feel, I want them to realise that they have something to give. I think everybody is important—everybody has a story, a life.

Sometimes things are very sad and the voice changes. When it's peaceful, it's the same thing. It's like the waves in the sea. If the wave is angry, it's different. A person might retell something that is very difficult in their lives and you feel it in the voice. For me, the first sound is very important. By the time I come with the crew, the person feels at ease and I'm thinking of the audience.

In my interview of a person with the crew, although I'm talking about the same things, I can always go back to the first sound, which is the first voice. If I go to another image and you don't see the person, you [still] know the voice and it's very moving. This is how I do documentaries.

It comes from where I come from. I come from a reserve in the province of Quebec called Odanak, which means 'town'. It's only one mile by four miles and everything happens on that one mile. In those days we didn't have electricity or running water. We had an earth road and everything happened on that earth road. Most of the men were guides in the bush for hunting and fishing for many, many generations. That's what Obomsawin means—it's the one that walks in front.

At night we'd sit in the kitchen with oil lamps and maybe you have one man who's a guide telling a story. The stories always had to do with animals because they went hunting and they would always have stories about black bears and turtles. As a child you listen to this, and it's only the sound, the voice, so you make up images yourself. And my cousin over there has other images. The images are different in your mind. It really comes from that; listening for me is just diamonds.

EAI also heard Merata Mita talk about oral storytelling, which is a strong tradition here, and that it makes sense to make films as it's connected. It lends itself very easily for our people to make films because we come from a tradition of oral storytelling. I also love that you use your own voice to narrate most of your films, as a particular touch of yours.

AOMy experience in life was with our people and it was very painful for many years. I was always looking to make things better for others. By listening to how people feel, I want them to realise that they have something to give. I think everybody is important—everybody has a story, a life. I could make a wonderful film about anyone. Why? Because I'd listened to them. It's as simple as that. I think our people are beautiful and for the longest time we were told we're so ugly. It's not true. Everybody has feelings and has something and many people have never been heard or there was no interest. I have interest and I think it's so important to make things better, to be understood, to make people realise that they have something to give, that they're beautiful.

It's to make people realise the good they have in themselves and that they can bring it out. They can make other people feel better, they can make themselves feel better, they can make changes. It's terrible when you think you can do nothing, that you can just drink yourself to death or take drugs. There's other ways to cure yourself. There's a film I made called Our People Will Be Healed (2017), with the Cree people in Norway House in the northern part of the province of Manitoba in Canada. That film is so special because it shows you the beautiful people; the value of the language and how everybody's capable of doing great things. I really believe this and I know it's been proven many times.

Before I was making films, I was singing. Eventually I was invited to go to a classroom and I have not stopped ever since. I've done hundreds of school visits across the country and no matter where I go, I'm always so happy if I can see children. I also see the progress, the people who are not Indigenous and have feelings that they never had before, and they want to know. Love is happening all over the place. It's true—I know that. That's why I keep telling it to people. —[O]