Survival Kit 8: A report from Riga

Survival Kit, an annual art festival organised by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art in Riga, was launched in 2009 as a DIY event responding to the global financial crisis. With each iteration, the festival invites participants ‘to respond to the changes occurring in the world today and to reflect upon the possible survival strategies’, through a series of exhibitions, workshops, performances, lectures, and discussions. The overall intention is to tap into issues affecting society in both particular and general terms, including the prevalence of empty, un-used spaces in Riga. (The origins of the Free Riga movement have been pinned to the summer of 2013, when ‘Occupy Me’ stickers began showing up on the city’s empty buildings concurrent to Survival Kit’s 5th edition.)

Indeed, the use of carefully chosen spaces is central to Survival Kit’s conceptual framework, and this year’s iteration—curated by LCCA Director Solvita Krese and LCCA Curator Inga Lāce—was no different. The exhibition this year, which featured roughly 30 artists, took place predominantly across two sites from 8-25 September. The key venue was C.C. von Stritzky’s 19th century villa, an abandoned mansion on a former brewery complex open to use for the first time in years (apparently, it was once a KGB interrogation centre during the Soviet occupation). The other site was the Pauls Stradins Museum for History of Medicine, which was opened to the public in 1961 after distinguished Latvian physician Pauls Stradiņš bequeathed to it the private collection that he established in the 1920s and 1930s. It is, according to the museum’s own website, the third largest institution of its kind, and it presents a world history of medicine infused with the ethnographic language of the 19th century.

During the festival there was only one permanently displayed art work at the Paul Stradins Museum, not counting the performances that took place there, or the museum’s usual exhibitions that were absorbed into Survival Kit 8’s overall frame. (These include reconstructions of Neolithic suturing, complete with dioramas, as well as an incredible installation showcasing Soviet-era research into outer-space and medicine.) In the basement was an installation by Floris Schönfeld that outlined—as the title suggests—A Brief History of the Damagomi Group. This included a single channel video that charts the story of a fictional outdoor club founded by a group of academics, researchers, and spiritualists living in Northern California in 1932, and named after a word used by the Pit River Tribe that roughly translates to ‘spirit animal’. By the late-50s, the narrator in the video explains, the group—having reformed after the trauma of World War II—bought a piece of land to live on, where they conducted important research on ‘deep listening’. This led to increased popularity, a member swell by the 1960s, and tensions which created a split in 1970, when the group essentially disbanded. The film ends as it began; with a shaman from the Pit River Tribe explaining how humans are both animal and spirit combined—neither one nor the other: ‘that’s why we have a hard time’ and ‘need help’.

A familiar tale about the rise and fall of a transcendental human quest, A Brief History of the Damagomi Group was a good introduction to Survival Kit 8’s theme, encapsulated by the title, ‘Acupuncture of Society’. The festival sought to explore art’s ability to locate pressure points within contemporary life, its ability to offer some kind of therapeutic relief (if at all) to the human condition, and its relationship to both transcendental and holistic healing practices, as well as spiritual and new age fads that have become commoditised phenomena.

Central to this investigation was the programme of performances, talks and interventions, including a two-day interactive happening orchestrated by Paul Philipp Heinze, artist duo J&K, Linards Kulless, Christoph Mühlau, Melissa Steckbauer, Magda Tothova and Suse Wächter titled Mending and Bending, To Riga with Love, which included sensoriums, holistic healing, performances, installations and workshops (including natural fabric dying) set up in the garden of the Stritzky villa, within which a majority of the exhibition was staged.

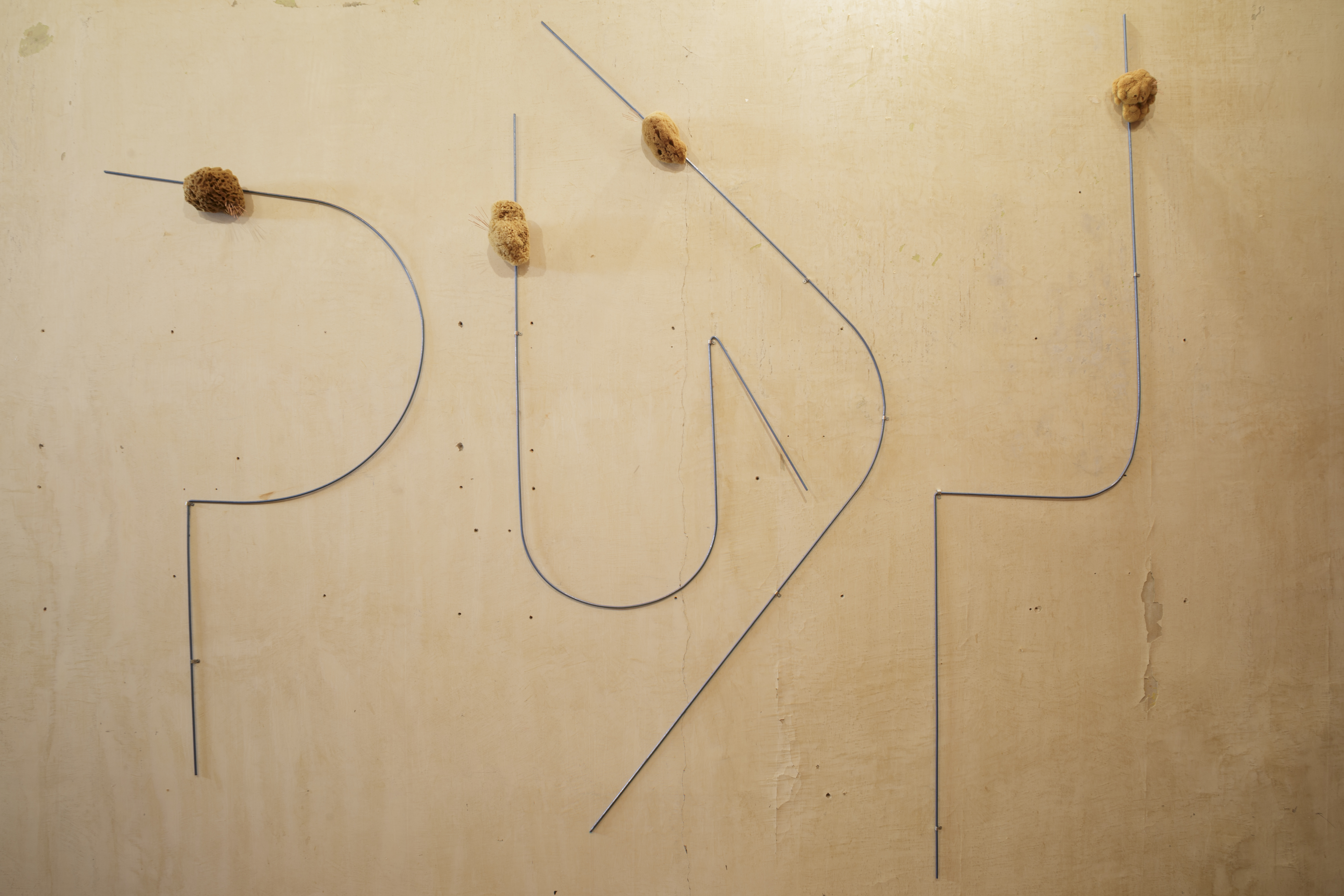

Here, art works considered the varying potentialities and contradictions that exist in our all-too-human desire to become better selves in a better world. But the exhibition did not fall into sentimentality, starting, instead, with a severe and highly ambiguous work by Lea Porsager: Cunning Meridians—Shock Therapy by Way of Used Needles. Constituted of natural sponges penetrated with acupuncture needles arranged on iron sticks composed along the wall of the Stritzky villa’s entrance hall, the arrangement was accompanied by a wall text that included a line from the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom describing a man sticking 2000 needles into a woman’s breast only to ejaculate on the final needle’s insertion.

Porsager’s introduction staked a sharply ambivalent message in the heart of Survival Kit 8’s theme; one that brings us back to the story of the Damagomi Group over at the Medicine Museum, where Schönfeld points out the reality of the inherently contradictory—and conflicted—human condition (at once animal, and divine). By locating the symbol of the acupuncture needle and the connotations that come with it—from eastern medicine to its association with new age culture in the western world—in Marquis de Sade’s most violent and abhorrent tale of four libertines living out their debauched fantasies on children and teenagers, Porsager set an uncomfortable tone for the exhibition at the Stritzky villa, underscored by the irony that occurred in works throughout. Sade’s tale, after all, was set during a period of what he viewed as French decline, when wars drained both state coffers and the substance of the people, and swindlers of the highest rank led a culture of depravity and profiteering.

In the works that followed, spiritualism came with a hint of deception. Goldin+Senneby’s installation Zero Magic (2016), which offered an unveiling of finance’s relationship to the (literal) art of illusion as presented in a vitrine containing a series of objects and corresponding texts that revealed occasions in which magic was used for corporate, and colonial interests.

These included the ‘Light and Heavy Chest’ conceived in the 19th century by magician—and father of modern magic—Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, which was used in colonial Algeria as a performance of European superiority, for which the trick was framed as a spell that could drain a man of its strength. It involved a chest containing an electromagnet being lifted first with ease and then, after the magician turns the magnet on, is lifted without success by a strong adult, all with the extra flourish of an added electric shock. Another spell detailed the fascinating origins of the dollar box, apparantly created by corporate magician Bill Herz and CEO of Snapple Beverage Group Inc., Mike Weinstein, in order to attract distributors to its flailing drinks brand, which Triarc Beverages had just acquired for USD300 million. (The trick literally involved a box with a Snapple banner filling up with money during meetings with distributors, presented under the slogan, ‘the magic is back’.)

The sense of revelation in Zero Magic—in which magic’s ulterior motives are uncovered—was echoed, too, in the spirituality presented in Marte Johnslien’s installation, Shouts from Silence (2014), which included stills from a video presented on a structural grid. These stills captured (western) faces from a protest staged in support of the Dorje Shugden worshippers in Oslo during a 2014 visit from the Dalai Lama. The topic points to the discord that exists within seemingly peaceful movements; the Shugden community and the Dalai Lama have been at odds since he rejected a publication that inflamed sectarian rivalries within Tibetan Buddhism in 1978. A series of three paintings titled Action Cushions (8-10) (2016) were shown on the floor next to this installation. They were positioned as meditation cushions and produced according to the method of Dharma art advocated by Chögyam Trungpa—a controversial figure known for disseminating the doctrines of Tibetan Buddhism to the Western world, and an advocate of what he called ‘crazy wisdom’ (he apparently died of complications from alcoholism).

But despite appearances, Survival Kit 8 was not as cutting as it seemed. Marcos Lutyens, for example, created Haptic Spectre (2016). This was an experience of recorded hypnosis, in which visitors were invited to sit at a covered table and feel a pair of ceramic objects hidden behind a curtain while listening to the artist’s voice imploring listeners to feel the object under their fingertips. The objects behind the curtain were modelled on a reflection the artist saw on the protective covering on the beautiful ceramic fireplace located in the same room; it was a crucial compositional detail that articulates how Lutyens employed the language of spiritualism in order to firmly locate the viewer in an embodied experience of the present, framed by the Strizky building itself, and the works assembled within it.

Likewise, a series of colour pencil on paper drawings produced between 1977 and 1988 by artist and philosopher Zanis Waldheims, all made in the style of geometric abstraction, offered striking examples of thought forms unencumbered by a certain kind of jaded production. Created after Waldheims landed in Canada in 1952 after fleeing Latvia during World War II, the works express a deep philosophical search by a practising philosopher trying to visualise his understanding of the human mind and its relation to both trauma (Waldheims was deeply affected by the events of World War II), and the ability to overcome it. (A testament to the devotion with which Waldheims approached his remarkable search, is the existence of 600 drawings and 50 small sculptures to his name.)

Perfectly positioned next to Katarzyna Przezwanska’s beautiful 2016 sculptural assemblages (all untitled) inspired by sacred geometry, in which minerals, shells, and other natural objects are composed like non-denominative shrines, Waldheim’s vibrant drawings articulated an earnest and vital investigation into the human mind and the balance it is capable of producing. All of which brings us back to Schönfeld’s work, and the way his video history of the Damagomi exhibition starts and ends: with humanity positioned between the animal and the spiritual, and the place between the two, where humans belong. —[O]

http://www.lcca.lv/en/survival-kit/