David Salle Spills All at Lehmann Maupin Seoul

For Seoul Art Week (1–10 September 2023) Lehmann Maupin showed American artist, author, and curator David Salle at their gallery in Itaewon.

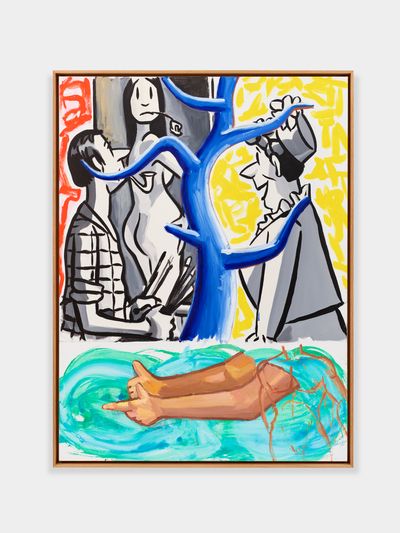

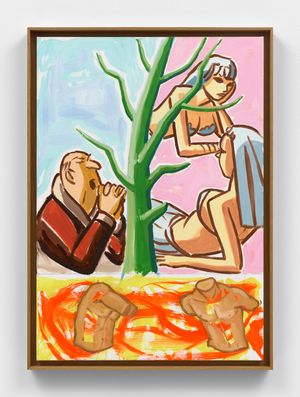

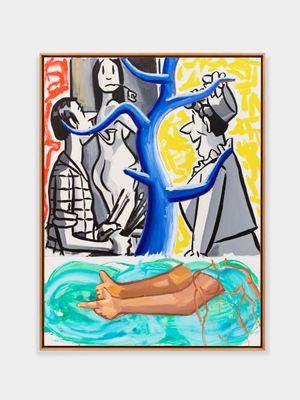

The exhibition of new paintings, World People (5 September–28 October 2023), features the final iteration of his 'Tree of Life' series (2020–2023), which was influenced by illustrations by legendary The New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno.

Catching him moments before the exhibition opened, Ocula Director Rory Mitchell sat down with David Salle to discuss his start in writing, his discovery of Peter Arno, and the paintings hanging on the gallery walls.

I'm a big fan of your writing, particularly your book How to See: Looking, Talking, and Thinking about Art (2016). When did you start writing about art?

The first piece of writing I did was for a friend of mine who was the editor of The Paris Review. Another friend was the culture editor of Town & Country, a magazine that covers old-school weddings, horse shows, and that kind of society nonsense.

She had this crazy idea to hire me as the art critic, and it all started from there. She was a great editor and we worked on many pieces together, many of which are in that book. It took off from there.

Has writing informed your painting?

It has definitely impacted my work. The act of deeply engaging with someone else's work and trying to imaginatively project yourself into their process and decision-making to understand exactly what they have made is key. Writing is a very good thought exercise, I would recommend it to anybody—that deep-dive benefitted how I think about my own work.

I love the analogy you use about what makes a good painting: the delivery of a joke is more important than the joke itself. It's not the 'what' but the 'how' that makes a painting successful. Can you expand on this?

Well, it's a funny thing. Of course, people focus on the subject matter because it's the first thing your eye can latch onto and the first stage of appreciation. But of course, that is only one layer of a painting's identity and maybe not even the most important one.

Recently, I've found myself saying to people: What does it feel like to look at? What is its emotional register? Is it funny, silly, slapstick, or antic? Or is it the opposite: subdued and sombre?

Again, by engaging with other people's work, I'm trying to answer that question for other artists. When posing it to myself, I find to my surprise that the emotional, or vibrational temperatures of the paintings in this show are so vaudevillian, antic, and silly that you can almost hear a shrill clown shriek echo in the room. That's not at all how I think about them myself, but it is there.

How does this play into the works in your Seoul show?

A good painting has an immediate impact, but rewards prolonged looking.

Often in my paintings, I use imagery that also alludes to the act of painting. For example, in Tree of Life, Envy (2023) you can see a cup of coffee that is being spilled. The spilling from the cup echoes the act of paint being poured on the canvas. This refers back to some of my earliest paintings in the 1970s, which include these jokes about painting.

There's something about this arrested spill which is a funny painting joke because obviously, it's static.

The bottom panel is a very finely calibrated counter-balance to the top in how it differs. The line and gesture are different, but somehow they need each other. That's the goal.

When you've spoken about the imagery and choice of subject matter in your paintings, you've said it's often a simple decision of whether something's painterable or not. What makes something paintable for you?

It has everything to do with academic values like form, and volume, and contrast. The Arno characters are good subjects for my paintings because Arno already depicted the human form in terms of light and shadow and that's what makes them painterly. The same as how a photograph is an appropriate subject for a painting because photographs are essentially a record of light and shadow—it's the light that makes the image.

Arno is much more than a guy who made clever line drawings. The drawings have a sense of form that then me as a painter can respond to, amplify, automate, and manipulate.

Was that your primary interest in Peter Arno's work?

When I first discovered Arno, it wasn't because I was looking for him. Rather, I saw an image of a couple he drew in a design annual from around 1942. The freshness of the value pattern—the alternation of lights and darks—was a bingo moment of knowing just how I could translate that into actual painting.

Composition is obviously very key in your paintings? Can you talk about this?

Going back to the early 1980s, my paintings have always been 'all over compositions'. That is to say they are not artworks you could rotate that would be equally effective from any angle.

Rather, there's a sense of dispersal of the material, the images, and the elements throughout the space in a way which is not singularly-focused.

From the very beginning, my work was about working with the space of the whole canvas—more circuitous, more arabesque. I feel I have more of a kinship to spaces that keep your eye moving.

Have you always made these multifaceted compositions?

I started very early on when I was in my twenties at art school. Not so complex, but very much in a nascent form.

This is the final iteration of your 'Tree of Life' (2020-2023) series. Was this the first time you had painted trees as a central focus?

It was the first time I had made a painting with a central focus. The body of the canvas is in half vertically. This is the first thing you learn not to do because whenever you divide a rectangle in half the space goes dead. Things should always be off centre as this creates tension, and tension creates interest.

So what I did was defy that cardinal rule and put the tree in the middle and divide the canvas in half, which provided a bifurcated stage where these Arno characters could then appear in an oppositional tension.

The addition of the underneath panel came to me in a flash one day. It was the idea of the roots of the tree penetrating to the surface of the earth, spreading out and gathering nutrients from whatever is down there. It became a metaphor for the past or collective history.

Main image: David Salle in his studio, 2023. © David Salle/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo by Frenel Morris.

Selected Artworks

182.9 x 248.9 x 3.8 cm Lehmann Maupin

Request Price & Availability

76.2 x 53.3 x 2.5 cm Lehmann Maupin

Request Price & Availability

142.4 x 106.8 x 4.1 cm Lehmann Maupin

Request Price & Availability

198.1 x 137.2 x 6.35 cm Lehmann Maupin

Request Price & Availability