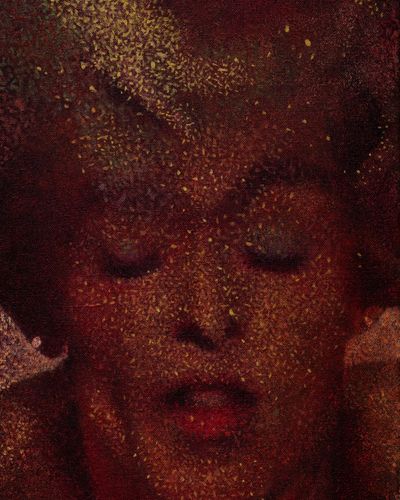

A sense of wonder radiates from the glittering surfaces of Louise Giovanelli's paintings. Cropping a variety of sources including TV and film segments and motifs from early Renaissance paintings, Giovanelli gives significance to otherwise overlooked details.

In her upcoming exhibition As If, Almost at White Cube in London, Giovanelli uses cropping as a method to explore themes of devotion and worship, zooming in on Mariah Carey's legs so that they resemble 'Corinthian columns', along with hands clasping a glass in an image drawn from Ab Fab, which she equates to Caravaggio's Bacchus paintings.

I spoke with the artist ahead of her show, learning more about the different techniques she uses to invite a slower viewing process, as well as her experiences studying at the Städelschule Frankfurt under Amy Sillman.

Your paintings take details from different source imagery, which are then cut off from their original context. Could you tell me a bit more about what draws you to the subjects you choose?

It's a bit of a mixture of found imagery, including things I come across in film, TV, advertising, and other stuff that pops up in daily life.

I also create my own images sometimes. The series of hair paintings, for example, are all based on wigs. I controlled the lighting to create the images myself.

Sometimes it's important to control everything to get the image that I want. Other times, something will just spark my curiosity in a found image, and that will be enough to spur an idea for a painting.

My work is very image-driven—the image appears first, and the painting later. Whereas for some painters the image comes through the act of painting, I start with an image and change it along the way, but that initial trigger is very important.

Are there motifs you keep returning to a lot until the series is finished, or is it something more natural, that flows from work to work?

I only ever move on from a series because something else begins to fascinate me. Painting is a way for me to work things out, and a way to discover what fascinates me of a particular image—that's why I work in series. It's not that I become bored of specific images, it's just something else might come into my orbit.

What do you hope viewers draw from these details?

The cropping device is probably the earliest device I ever used, and I think it's a way of dislocating or decontextualising the image. Cropping tunes into the part of an image that I find the most significant, so I guess that's what I want the viewer to do—to look at parts that might otherwise be overlooked in certain scenarios.

I don't want my paintings to become overly illustrative, because I find in other artworks when that's the case, I get bored or they're just a bit dead to me. I like there to be some sort of gap where I as the viewer can add something. I try and add that space of mystery and ambiguity in my work.

How did you arrive at your method of applying thin layers of pigment to create light and shade—is this something you developed during your studies, or after?

It was a bit of a combination, really. I first encountered it when I began my BA at Manchester, and a tutor saw I was interested in oil paint, and I was making that transition from acrylic to oil paint.

When you make that transition, you really should adopt that layered technique because it's so different to acrylic—acrylic is a kind of liquid plastic. Oil is pigment suspended in shiny oil, so it lends itself well to lustre and glazing and light effects.

So, I was introduced to it there, but I instantly became very fascinated with it and wanted to learn more, so I just read lots of books and studied old paintings. That was how I found out, for the most part—by looking at pre-existing paintings and figuring out how they had done it.

I went on lots of pilgrimages to see old master works at galleries and museums—to excavate with my eyes and see how artists managed to do certain things. I suppose that's how lots of paintings by artists were done, by looking at what others had done before.

How long does each painting take, roughly?

It's hard to say, because I work on so many at a time and because of the slow nature of how I do things. A lot of the time you're just waiting for paint to dry, so there's a lot of bouncing around between works. I made this show for White Cube in five months.

What is a typical day in the studio like for you?

Three to four months before a show, I'll be in the studio from 6 in the morning to 6pm, because I like the morning.

You graduated from the Städelschule Frankfurt in 2020, where you studied under American painter Amy Sillman. How was your experience there?

Yes, she was my professor. In Germany, it's a little different—if you want to go to one of the schools, you apply directly to the professor. You don't apply to UCAS, like you do in the UK. So I applied directly to Amy to be in her class, and it was fantastic.

It was a very eye-opening experience. The whole school has a very hands-off approach. Professors don't come in for months at a time, then they come and work with students intensely for, say, a week, and there's no studio time or anything—you just have to be there and listen to the professor and do what they say. They are king and you're a disciple, almost, which is different from my BA, but I loved it.

You get a lot of freedom—the studio spaces are really big, and there was no coursework or exams or marking scheme. All of that bureaucratic nonsense that we have in the UK wasn't there. We could just make art, have crits and seminars, and then you just leave. There's no pass or fail—you've just had an experience.

You have mentioned the photographer Dirk Braeckman as an artist you are inspired by. Navigating the tension between materiality and representation is key to your work. Were you always set on painting as your preferred medium?

I think if I wasn't a painter, I'd be a filmmaker or photographer. This is why I like Dirk's work so much, because I consider him to be a painter although he's a photographer, because his consideration of the surface is exactly the same as a painter's would be. He has that same understanding.

He has a painter's brain, almost—he considers light phenomena, and he kind of manipulates the surface so it reads a lot more like a painting. I guess that links to my work in a certain sense, because light is so fundamental to everything I do.

There's also a slowness in Dirk's work, as there is in Tarkovsky's films. They're moving so slowly that they are almost aspiring to the condition of painting, and this idea of slowness and hard looking at stuff is something I'm really fascinated in.

Your upcoming exhibition at White Cube includes references to Old Master paintings, which has been a focus of yours for a while, along with contemporary figures such as Diana Ross and Mariah Carey. Could you tell me about your decision to draw these elements together?

For a while it was intuitive—I didn't really realise why I was doing it, I was just painting what I wanted to paint. But after a bit more reflection I realised I was interested in the idea of devotion and capturing instances of contemporary worship.

We have these icons, and I think there's almost a religious tone to everything. Even though many of us would call ourselves atheists now, we still behave in a way that's spiritual, and worship certain individuals.

In my paintings of Mariah Carey, it's not always important for people to know who it is I've depicted—that's why I zoomed in on her dress. It's more the idea of the pop idol. It could be any pop idol. And again, light is so fundamental in all of it. A pop star's shiny dress almost becomes a kind of religious altarpiece.

Repetition is key to your work. You have mentioned that it allows you to explore certain motifs and nuances over time, and also draws the viewer into the ambiguous narratives that you create. Could you tell me a bit more about how you are engaging repetition in your White Cube exhibition?

There are a few repeated motifs. The curtains are an ongoing series, so I guess you could call that a motif. There are a few of the hair pieces, and a new motif I've introduced in this show is a wine glass.

A few paintings have this idea of a goblet or hands holding the wine glass, which is a still from Ab Fab, but another one is from an old Hollywood film. It's just a woman looking through this wine glass.

I'm still trying to work out why I painted it, but I think it has something to do with the holy communion, or the transcendental. I was also thinking a bit of Caravaggio's Bacchus paintings.

The zoomed-in paintings of Mariah Carey are new, in a sense—the predecessors of that series were the dress paintings, whereas these focus on the legs almost as these Corinthian columns.

A lot of the paintings have this very exaggerated, stretched feel to them. There's something architectural about that. Something monumental. And I guess it's a bit out of the ordinary. That's the way that we perceive TV and film—everything becomes really stretched.

What's next for you?

I'm going to spend some time working in New York—a bit of a self-directed residency. Then I will have another show with my other gallery, GRIMM, and then probably some more shows with White Cube in Hong Kong and Paris. —[O]

Main image: Louise Giovanelli. Photo: William Waterworth.