Shinuk Suh's gaze traces the dissolving boundaries that distinguish one individual from another, against the backdrop of modern industrialization and contemporary capitalism. His prehensile vision realized through kinetic sculptures, Suh's latest exhibition continues the trajectory of his previous steel-fabricated works, now upgraded with stainless steel as the primary material. Through this evolution, he narrates and explores Korea's industrial and societal landscape, both past and present.

Shinuk Suh's practice casts light over factory production lines that dictate human labor, often down to their finest movements. Heralded by the Jacquard loom patent in the early 1800s, around-the-clock spinning and whirling of machines on the factory floor became the image representative of modernity. Factory floors are not without labourers who use their body and limbs to productive ends. However, the industrial machine and its production lines are generally perceived without the person, the florid spinning and swirling of bits and pieces distracting from any attention to human hands.

These discussions are rooted in the concept of interpellation by the French philosopher Louis Pierre Althusser, who argued that societal systems mould individuals into a uniform way of thinking, where individuals imagine themselves as integral components contributing to society. We Have the Same Dawn and Night as the title states, and paradoxically this sameness only emphasises the system over the individuals comprising the collective 'we.' Shinuk Suh peels back the layers to unveil the contrasting scenes between conspicuous factory mechanisms and the human mechanisms that adapt and conform to them.

Inside the exhibition hall, an elaborate contraption of unibody frame with a control box on each of its two peripheries. Five circular-motion motors are affixed to the frame, each responsible for moving a pair of objects. Three of these motors are linked to circular pan-plates, which rotate rods clockwise, mimicking a circular sifting motion on the pan. On the floor below lies an acrylic representation of the human body. The three humanoid objects, each distinct in shape and curvature, symbolically respond to these movements as they hold pans, collapse, and fold. On one side of the frame composed of rounded plates, rods attached to the frame rotate overhead. On the opposite side, intersecting frames house a rotating motor at the center axis. This motor moves a silicon-cast hand through all four planes of the frame, gently grazing the four humanoid objects suspended from the frame's top. These humanoid figures are crafted from textiles and textures familiar to us: a half-zip hoodie, jeans, textured leather reminiscent of human skin, and finely shaped acrylics. They evoke contemplation on the multifaceted nature of humanity in reality.

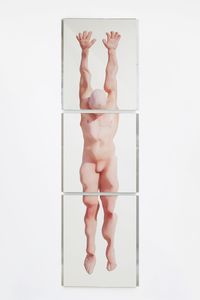

Suh's presentations in this exhibition were created using Blender, a free and open-source 3D computer graphics software tool. He specifically employed the Geometry Node function of the software for new experiments involving nude shapes and stainless steel materials. The artist's interest in psychoanalysis led to his previous works, where he used 3D graphics software tools to visualise brainwaves. Geometry Nodes in Blender is a node system that enables procedural control of data in a mesh or curve object. This allows manipulation of lines and surfaces into other mesh or curve objects, encompassing movement, rotation, and sizing along the X, Y, and Z axes. The humanoid objects fixed to the unibody frame or suspended from wall-mounted mirrors were created using this node system. Although they share a common shape, they exhibit varying forms achieved through subtle alterations in input. The shift from steel to stainless steel is notable as both materials are emblematic of industrialisation and factory machinery, but stainless steel, in particular, holds a special place in Korea's industrial development, thereby localising the artist's narrative to Korea's industrial journey and societal evolution.

Through the silicon hands and distorted outlines of human body within the exhibition hall, Suh unveils the tragic narrative imposed upon our lives by industrialised society. However, this tragic tale can transform into comedy with the subtlest change in perspective. The rotating mechanisms attached to the unibody frame, indicated by arrows tracing their circular paths, interact with altered humanoid forms. The mirrored wall reflects not only the contraption but also the spectators facing it, inviting us to witness the entirety of the system that envelops us. A fleeting sense of bistable humour flickers in the flailing clothing items and soft silicon hands, which endlessly rotate in vain, gathering dust and wearing away over time. Yet, this humour lacks genuine comedic delight, leaving behind a tinge of cynicism. This cynicism, in turn, reinforces the realisation that we indeed exist within an extensive mechanism, a complex system of industry and society.

Press release courtesy GALLERY2.

204, Pyeongchang-gil

Jongno-gu

Seoul, 03004

South Korea

www.gallery2.co.kr

+82 2 3448 2112

Tuesday – Saturday

10am – 7pm