AING, AING is Thy favourite mantra,

Thou who art both form and formlessness,

Who art the wealth of the lotus face of the lotus-born,

Embodiment of all gunas, yet devoid of attributes,

Changeless, and neither gross nor subtle.

None know Thy nature, nor is Thy innerreality known.

Thou art the whole universe;

And Thou it is who existeth within it.

Thou art saluted by the foremost of Devas.

Without part Thou existeth in Thy fulness everywhere.

Ever pure art Thou.

—Sarasvatistotra (Tantrasara)

For those attuned to it, in recent years Tantra as an idea and a way of being in the world has been steadily gaining currency in contemporary artistic practice. Insofar as it is possible to offer a crystalised definition of it, Tantra is a term used to describe ways of connecting with the cosmos, the micro to macro.

In the sphere of art, Tantra was propagated in the west by curator and collector Ajit Mookerjee from the early 1960s onwards. Mookerjee claimed Tantra's ultimate aim was the attainment of 'a state of perfect bliss'.1 Through exhibitions including Philip Rawson's seminal 1971 Tantra at the Hayward Gallery in London, many artists began to engage with as well as collect and live with tantric artefacts. There is still much study to be done on revising the dominant art histories so that they pay proper tribute to the influence of other cultures and traditions, including of Tantra on modernism and minimalism. In the meantime, it is important to acknowledge that these histories exist, as well as perhaps to contemplate the assertion of psychoanalyst Carl Jung that there are universal patterns and images that are part of a collective unconscious operating across cultures and time.

This exhibition brings together the work of two artists, Mahirwan Mamtani and Harminder Judge. Separated by generations and geographies, they are united in a declared interest in Tantra, and upon first encounter their work might also appear to share aesthetic qualities. Yet further looking and learning reveals definite differences. Mamtani's work remains closely visually aligned to the schematics of Mandalas; Judge's work is more open with swathes of unadorned space, it is less directive. The works are about what we have in common with the universe, as well as who we are as individuals and how we find our place in it, our home.

Mamtani was born in 1935 in present-day Sindh province, Pakistan, and fled partition with his family to settle in Delhi. He taught himself to paint while lying on his sickbed in a refugee camp, a fact recounted in his exuberantly lively biography, Indus to Isar2. Like many Sindhis who were uprooted to India during partition, he fell into a cycle of odd jobs, but he nevertheless found time to nurture his passion for art and making. Initially studying at the Delhi Polytechnic, in 1966 he won an opportunity to study in Munich, Germany. In Germany, Mamtani immersed himself in the culture and the art scene. He succinctly articulates how what he saw enabled him to determine his own visual vocabulary:

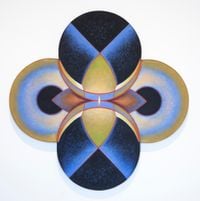

I saw many exhibitions of Mondrian, Malevitch [sic], Josef Albers [...] -they all had a geometrical approach. It connected me to Indian Tantra art, the book published by Ajeet Mukherjee [sic] in the early 1960s. I started experimenting with the geometrical Mandala form, and then ultimately four-petal circles construction became my symbol of expression. For me it represented wholeness.3

Through his identification and engagement with Constructivism, Mamtani developed 'Centrovision' based on an 'impulse to transform my experience of the world into a vision leading to the bindu. This point at the beginning and end of the inner and outer space, where the micro-macro unity is present.'4 The soft, gradated hues of his paintings contain and channel movement across the surfaces of the orderly and distinct sections. Although he has made their shapes and symbols his own, the diagrammatic forms of the Mandala are never left behind. These works speak of transformation and the potential to explore alternative dimensions, but they are also intensely personal. For Mamtani, a viewer will make of them what they will. Mamtani has in his possession almost 3,000 of his own artworks, which constitute a kind of diary documenting his transcendental relationship to art.

The works by Mamtani gathered together for this exhibition at Jhaveri Contemporary are from the Neo-Tantric period of the mid- to late-1980s. A term invented on the occasion of the exhibition Neo-Tantra: Contemporary Indian Art Inspired by Tradition at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1985, that included Mamtani alongside Biren De, GR Santosh, Sohan Qadri and others. One of the curators, LP Sihare, at the time the director of the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, described it as 'art [that] is not tantra but related to it, coming out of it in some way'5. Here Mamtani's paintings are seen alongside works by Judge for whom Tantra might not have been such an explicit part of his cultural upbringing and something that he could draw on directly, but rather a set of ideas and energies for which he has more recently developed a profound appreciation.

Originally from the north of England, Judge is currently enrolled at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. On the wall of his studio he has scrawled an eclectic set of quotes by the philosophers Democritus and Ludwig Wittgenstein and one from the artist Francis Bacon that reads: 'I want a deeply ordered image, but I want it to come about by chance.' Originally trained as a painter, to make his current body of work he has developed a ritualised process over which he has tight control, apart, crucially, from when it comes to the visual composition of the main, 'front' area.

Using knowledge of materials acquired when building a house on the edge of the Peak District (part of a strategic determination to make money in a time of economic gloom), and with allusion to Renaissance frescos and Indian reverse glass painting, he has devised an alchemical process whereby plaster, polymer and pigment are combined and shaped into a low-lying, elongated oval. Once dry, the works are turned over to reveal the workings of the pigment.

When the surface has been revealed, Judge fastidiously sands, waxes and oils them. If you did not know how these works were made, you might assume they were cross-sections of unfathomably large precious stones, or even imagine them to be experiments in photography. Sometimes psychedelic swirls appear; sometimes landscapes; sometimes they are reminiscent of dyed fabric; sometimes they are like a heat-haze. Their oval shape suggests Shiva lingas and the Brahmanda (the cosmic egg). Symbolic of the god Shiva, the divinity without form, the source of the universe, the infinite into which everything merges at the end of time, lingams are understood to be man-made for worship, carved from stone, but can also be found in nature. Here they are emerging through Judge's controlled process. He himself likens them to Tantric works on paper by anonymous modern painters from Rajasthan. They share not only a similar form but often are also characterised by flecked and bleeding pigments.

Judge's titles for this exhibition all relate to the night of his great-uncle's funeral. Writing evocatively about his encounter with death and a great-uncle he had met just once before, he describes how '[the body] burned throughout the night, and he slept there, next to the fire, next to his father. [...] In the morning he woke next to his father and they sieved through the ashes, chunks of bone and teeth and steel jewellery.'6 Using the third person to talk about what happened, Judge takes a hold of reality and transforms it into a myth worth living for.

Mamtani and Judge maintain distinct, highly original practices that draw on Tantric doctrines and aesthetics. In interviews, Mamtani has quoted Goethe's 'everywhere a stranger and everywhere at home' and he has written 'Since 1948 after I left my native place Sindh on river Indus, I have lost the feeling for my home'. Judge's material process is born of building a house he will never live in, and his current work is guided by a singular experience at the funeral pyre of his great-uncle, which he attended just hours after stepping off an aeroplane. For both artists their relationship to Tantra is as much about the individual as it is the universal. It also affords them a tool with which to confront questions of displacement, as well as ways to connect with an ancestral home.

Rebecca Heald

1 Mookerjee, Ajit, Tantra Asana (Ravi Kumar: Basel, Paris, New Delhi, 1971) p.15.

2 Mamtani, Mahirwan, Indus to Isar (self-published, 2013)

3 Ibid., p. 41.

4 Tonelli, Edith. A. (ed.), Neo-Tantra: Contemporary Indian Painting Inspired by Tradition (Berkley: University of California Press, 1985) p. 28.

5 Greenstein, Jane., 'A View of India's Tantric Art', Los Angeles Times (25 December 1985).

6Judge, Harminder, 'Chapter 2 (a short excerpt)', harminderjudge.com/category/texts

Press release courtesy Jhaveri Contemporary.

3rd Floor Devidas Mansion

4 Mereweather road

Apollo Bandar Colaba

Mumbai, 400 001

India

www.jhavericontemporary.com

+91 22 2202 1051

Tuesday – Saturday

11am – 6:30pm