The sphinx, the mythological creature with the body of a lion and a human head, is one of the most powerful and iconic images of the Egyptian and Greek empires. The word 'sphinx' is derived from the Greek verb sphingein, meaning 'to bind' or 'to squeeze.' 'Decipher Me, or I'll Devour You' was the ultimate mystery of the Theban sphinx in ancient Greek mythology: according to the story, the sphinx watched every traveler who passed along a road. The traveler was made to solve a riddle that would either decide the end of their life, or a new beginning. The sphinx asked which animal had four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three at night. If the traveler could not answer, the monster would eat them. Yet the answer to her question was life itself: the stages of a man's life—beginning, middle, and end.

It is intriguing how the mysteries of life are intrinsically linked to time, the ultimate abstraction of the human mind. Time works as a compass that guides the path ahead, yet it situates us in our current moment. The loss of this reference has been painful for humanity; time is how we quantify our attachments. We collect objects, ideas, people; everything is an operation arranged within time. We must acquire everything in as little time as possible, counting down life that is fated to lose to death. In these acts of amalgamation, the collection of objects and ideas becomes the vital source of our place in the cosmos.

This place becomes empty when we ignore time, taking us to the theme of the exhibition: the mystery that surrounds our loneliness in the cosmos. The first spark of intelligence triggered our understanding of human loneliness, the sphinx that demands 'decipher or be devoured.' The human condition of today, and what philosophy understands as art asks the same question. Ignoring time and embracing our perceived individuality, human loneliness becomes an immense, dissoluble enigma.

Art history deals non-linearly with death, the absence and the void. Nature is comprised of atom and void, image and idea, writing and matter. The role of the artist, amongst others, is to bring these oppositions to light. We embarked together on this sphinx-like journey with cosmograms etched on stones from Andean, Valdivia and Maya civilisations, dating back to 2300–2000 BC, 1000–1500 BC and 600 BC respectively. The pieces represent the points of stars in the sky, our place in the universe—us and others. They deny loneliness, that absolute void; they offer proof of time and space, an answer that comes with the sphinx's question, something inherent to both the arrogance and kindness of earthly intelligence.

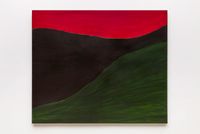

There are also the fertile fields of possibility and imagination. The mathematics imposed by such riddles try to delimit our field of speculation, to extract the creative power of nature—a river of strontium and copper, raining diamonds, icy moons, sodium lavas, impossible phenomena on the earth we live on. The frightening reality of sizes and distances, moving visitors, and everything seen and unseen in Marina Perez Simão's painting; the unidentified, gelatinous bodies in the sculptures of Eva Fàbregas; Luiz Roque's mysterious ceramic face; and the language-body of Michael Dean become representations of nature that overcome all doubts, introducing us to greater questions.

The limits of the body also reflect our loneliness and individuation. One of the enigmas of our present constitution: at what moment did we leave behind our vital drive, from our sense of collectivity within the cosmos? The process of Western control over ancient civilisations is one clue. For ancestral peoples, consciousness was unequivocally collective.

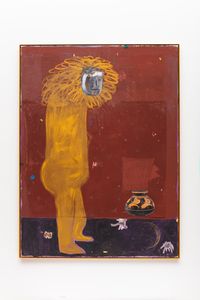

The individuation of man is unnatural to the body itself: two eyes, two hands, ten fingers and toes, the way in which we reproduce. This body is represented in Samuel Guerrero's mechanical hair, in Anna Uddenberg's ascendant climax, in Joanna Piotrowska's warped poses. Investigating the limits of our nature pushes us to ignore other existences, other visitors, or even a beast with a human head and the body of an animal, arriving at our civilisation through dreams or from other universes.

The untamed nature of the unknown consumes us from inside out; it is intrinsic within our human condition and psyche. Using the body as a receptor for complex creations, the existence and the state of art set in motion extraordinary transcendences, such as Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro's flower-body; the transfusion between human and bat in Lynn Randolph's work; and the augmentation of the body in the work of Berenice Olmedo. Such disparate lives become a single element of existence, returning the human separated from the collective, connecting us back to our cosmic salvation. The show intends to bring more questions than certainties, opposite paths leading us to where everything converges and coexists in the unknown.

Press release courtesy Mendes Wood DM.

Rua Barra Funda, 216

São Paulo, 01152-000

Brazil

www.mendeswooddm.com

+55 113 081 1735

Mon - Fri, 11am - 7pm

Sat, 10am - 5pm