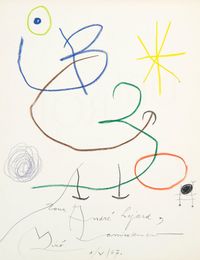

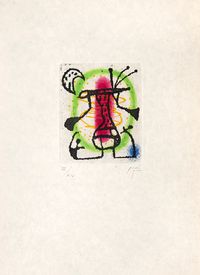

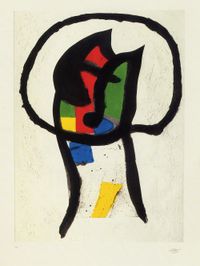

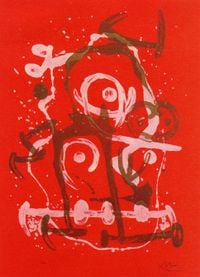

In Joan Miró's art, the Catalan native, uses simple shapes and symbols to form a complex and novel visual grammar. This surreal, formally driven style features across paintings, drawings, etchings, ceramics and sculpture.

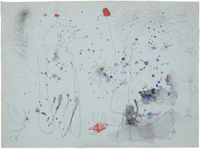

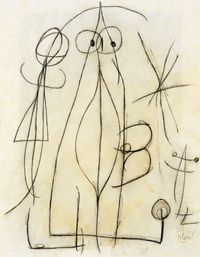

Read MoreAs well as a Surrealist, Miró was also a leader among the associated artists in explorations of the subconscious, particularly with automatic drawing. Most of his paintings began as automatic drawings in an attempt to escape the conventions of representation and the painting medium itself. Describing his 1925 painting The Birth of the World, Miró said 'Rather than setting out to paint something I began painting and as I paint the picture begins to assert itself, or suggest itself under my brush ... The first stage is free, unconscious.'

In each of his works, Miró is highly selective of which formal features of the landscape to accentuate, and which to discard. A prime example of Miró's poetic rendering of everyday scenes, The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) (1923–4) shows the Catalan landscape reduced into flattened planes. Minimal symbols represent the animals and vegetation; the titular hunter is a bare few set of lines against a flat pink representing the ground and a flat yellow sky.

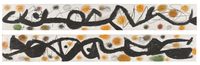

In 1928, Miró visited the Netherlands and became interested in the Dutch masters. Bringing home a set of postcards from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, he began a series of three paintings combining the Dutch regional style with his own unique visual vocabulary.

In Dutch Interior (I), a painting by Hendrick Martensz Sorgh is transitioned from an atmospheric image of a lute player performing for a woman to an energetic gathering of symbols across a flattened picture plane. Some aspects—such as the man's collar—have been accentuated, while others—such as the woman at the table—have been diminished or replaced. In this series, Miró's direct references to other images allow the audience to follow his path of inventive abstraction.

In the late 1920s, Miró became interested in the idea of the 'assassination of painting', within which he sought to escape or even destroy the traditions of bourgeois art and instead pursue more experimental forms. A work exemplary of this period, Painting (1936) was made with a mixture of gravel, sand and oil paint. The artist assured his dealer that rather than the work being ruined if some of the materials came loose when it was sent to an exhibition, the loss would 'make the surface . . . look like an old crumbling wall, which will give great force to the formal expression.'

In this period, he also experimented in collage and sculptural assemblage, as well as making costumes for ballet.

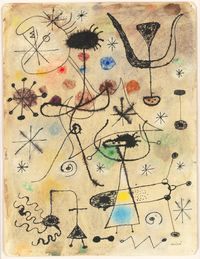

Throughout his entire career, Miró's Spanish and Catalan nationalism remained a key influence on his work.

Ernest Hemingway, spoke highly of Miró's Spanish pastoral painting The Farm (1921), which he purchased: 'It has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there. No one else has been able to paint these two very opposing things.'

During the Spanish Civil War, Miró was living in Paris. Deeply affected by the tragedy and tumult consuming his homeland, he was inspired to employ social criticism in his art. Works of this period also became more representational, such as in The Reaper—a mural for the Spanish Republic's pavilion at the Paris World Exhibition of 1937 that showed a peasant revolt.

Miró was also known for his Surrealist sculptures.

His earliest pieces were formed out of collections of found objects, such as Object (1936), whose media list is lengthy: 'stuffed parrot on wood perch, stuffed silk stocking with velvet garter and doll's paper shoe suspended in hollow wood frame, derby hat, hanging cork ball, celluloid fish and engraved map.' In the mid-1940s he turned towards ceramics, for which he embraced the full materiality of clay, often making intentionally imperfect pieces.