Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas

Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas. Courtesy the artists.

Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas. Courtesy the artists.

From their first audiovisual performances as Tashweesh in collaboration with musician and performer Boikutt, Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas' collaborative practice has utilised sound and video to create visceral, heart-thumping installations that are rooted in their present-day experiences.

Using field recordings, archival footage, found material, and text that they author or extract from various literature, Abou-Rahme and Abbas have developed a process-based methodology that unearths lesser-known narratives to subvert and complicate official histories.

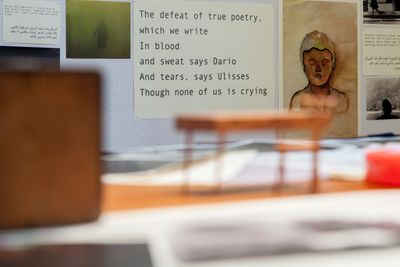

The Incidental Insurgents is a three-part project that was staged over three years between 2012 and 2015, and exhibited in a number of exhibitions and biennials, including the 13th Istanbul Biennial (14 September–20 October 2013), Pluriversale I at Kölnischer Kunstverein (4–29 November 2014), and at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania (4 February–22 March 2015). It is a defining work in the artists' practice, which—in their own words—'unfolds the story of a contemporary search for a new political language and imaginary.'

The first chapter, The Part About the Bandits, brings together four narratives based on protagonists from Roberto Bolaño's novel, The Savage Detectives; Victor Serge's memoirs from 1910s Paris; tales of Abu Jildeh and Arameet and their gang of bandits who rebelled against the British in 1930s Palestine; along with Abou-Rahme and Abbas' own texts. The playful installation, which highlights the anarchist—the underdog of political history—as the main official narrator, includes pinned images, a record player, and a cluttered work desk displaying books, magazine cutouts, and photographs. There is also a reverberating video of a landscape overlaid with pulsating text in both Arabic and English—characteristic of all their moving image works. The second installment, Unforgiving Years, offers another disjointed narrative through an assembly of images and objects that ponder the unfulfilled plans and ambitions of the figures featured in the previous chapter. Part three, When the fall of the dictionary leaves all words lying in the street, is a dizzying installation of video projections that fall on seven wooden watchtowers of varying sizes that cast long shadows across the spaces they inhabit.

In this conversation, the artists talk about And Yet My Mask is Powerful (2016), a two-part project that was printed as an artist book by Printed Matter in 2017, and exhibited at the Kunstverein in Hamburg between 3 February and 29 April 2018. And Yet My Mask is Powerful includes a five-channel video projection and installation of objects, including 3D-printed masks based on Neolithic masks found around Hebron and Jericho, and now kept in various private collections around the world. The title of the work comes from Adrienne Rich's poem Diving into the Wreck, whose verses appear throughout the video, which chronicles the return of the artists, along with young Palestinians, to sites of wreckage, wearing the 3D-printed masks throughout their journey.

You have said that And Yet My Mask is Powerful considers what happens to peoples, places, things, and materials 'when a living fabric is destroyed.' What did you hope to achieve with the fieldwork your undertook for the project?

And Yet My Mask is Powerful started from a point of acute urgency, but also from a sense of paralysis in the face of extreme violence against entire communities and living fabrics. This paralysis is very much connected to a state of collective trauma—a state of being that we have lived again and again in Palestine, when language and action fails you. As people and artists, we are living in a moment when entire living fabrics are being destroyed, and with this project, we were specifically thinking about the continued destruction in the last five years of Iraq, Syria, and Palestine. For a long time, we were unable to really look towards it—what can be said or done in the face of unimaginable violence? The erasure of entire communities is a violence enacted not just on the individual and communal body but also to places and things; lived structures, vegetation, and land, not to mention lived history, community, and memory. Ultimately, it is a violence enacted on our imaginary or any sense of futurity.

In Palestine, this history and present violence has been ongoing for 70 years. At the very heart of it are the villages that were destroyed in 1948, of which there are at least 412 that were depopulated. Why they became significant to us in this moment is because we became aware, through the scholarship of Palestinian thinkers—such as Esmail Nashif, Nasser Abourahme, and Samera Esmeir—and activists, that groups of young Palestinians were making returns to these sites.

Could you talk about the idea of return with regards to these young Palestinians, and visiting the sites in And Yet My Mask is Powerful with them?

What was most striking in the returns of these young Palestinians, and the scholarship around it, was how they were reconceptualising and reactivating the idea of return. Something unexpected happens in these contemporary returns. The destroyed sites emerge not just as places of ruin or trauma, but appear full of an unmediated vitality. The young people making these trips treat the site as a living fabric once again. They reactivate the disused spaces, camp out on site, eat, sing, dance.

The destroyed site of a Palestinian village, the very site of erasure, becomes the place from which to think about the incomplete nature of the colonial project. Your body now, in this space, refuses to be docile to colonial time and its imaginary, and momentarily embodies a time of your own making that is not located in past, present, or the present-future—it exists in a virtuality. Even in its fractional nature, this moment is extremely potent; it activates a potentiality to become unbound from colonial time.I

In this sense, our returns are part of this larger movement of returns. Our work is not really operating on a fictional realm, but in a realm between actuality and virtuality—what is and what could be. We are always building upon sites of resistance that are already being activated. When we made our returns, we chose to do it with a group of young Palestinians who had never made the trip before; that collective act and activation is a large part of the work itself.

The masks you feature are based on what are thought to be the oldest masks in the world. How did you get from an image of these masks online, to those you drew up digitally and produced as 3D prints?

The masks are a really good example of how we allow things to enter the work through the research; sometimes they become a major component in the project. We came across the oldest known masks to date while thinking of a particular stanza in Adrienne Rich's poem, which became critical to the whole project. In this stanza, she describes the dive into the sea for the wreck as a moment where she nearly loses consciousness; but then she writes: 'and yet my mask is powerful / it pumps my blood with power'. Here she is referring to her scuba diving mask, which allows her to breathe under water, giving her the power she needs to go to the site of the wreck. We began thinking about this idea of the mask as something that allows you to be, to breathe, and to act in environments where you should not be able to act or survive.

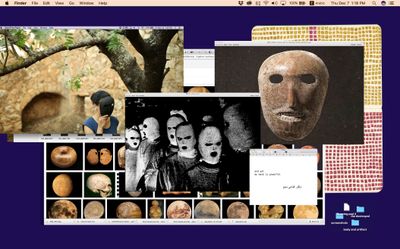

We were already interested in the idea of anonymity as a political position/act in our previous project, The Incidental Insurgents. Because we were thinking about these ideas that are mediated and take on a digital and virtual embodiment, we began with an online image search of 'Palestine Masks'. The results were predictably widespread images of young Palestinians wearing ski masks as they confront the Israeli military. But there were also images of what looked like prehistoric masks. We were, of course, immediately intrigued. These Neolithic masks—most of which were in private or semi-private collections in Europe, America, and Israel—date back 9,000 years and are in fact the oldest known masks to date. The Israel Museum in Jerusalem, which was designed to look like the silhouette of an Arab village before 1948, staged a very large exhibition of the masks in 2014.

As we researched these masks, we discovered that most of them had been 'bought', taken, or simply looted from areas in the occupied West Bank—mostly in the last 40 years—apart from two, which were taken in the 19th century. But what was most significant for us was how these masks were being used by the Israel Museum, and consequently the media, to reinforce various mythologies of the State of Israel; the map and narrative that the museum produced render Palestine and Palestinians entirely invisible. The more we dug, the more we needed to intervene into the contemporary myth-making of the state and to make our own claims on the masks. We were not able to go to the exhibition—one half of this duo is unable to enter Jerusalem under the law of occupation—but we could experience the exhibition virtually on the museum's site. It became important for us to think about the masks as a living material that can both activate and be activated. That's how we arrived at this initial step of hacking the masks to make potentially infinite 3D copies of them.

Your work demythologises the aura of these masks by splicing them into the contemporary and presenting them in proximity to local plants, materials, and artefacts. How would you describe the space you have opened up here through this treatment?

The work demythologises and decolonises the masks in several different ways. On one level, it is about rupturing the aura of the artefact as singular, by freeing it to be potentially infinite. This very much relates to Incidental Insurgents, which was about hacking archives and knowledge production to render everything an infinite copy that could travel anywhere and to anyone—something that was deeply impacted by Aaron Swartz's 'Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto', which obviously comes out of a long lineage of writers and activists. What is critical in this practice is how we can resist the fossilisation of things, and with it history and memory—life itself. How can the artefact mutate or be freed from being a dead fossil in order to become a living material that can be used by us now in a process of decolonisation? One of the masks was taken from the town of Al-Ram by an English physician in 1881. In his own narrative, he describes being chased by the villagers because they used the mask as an amulet—it turns out there was a Neolithic site there, and potentially, this mask was being used across a span of thousands of years. The moment it was taken and placed in a private collection in England, it was not only fossilised but positioned within a colonial narrative.

So, part of the work is to free this material and reactivate its latent powers. The masks were always about bending things and becoming 'the other' by way of concealment. When we thought about the power of these archaic masks in a contemporary register, we linked this concealment to forms of becoming anonymous, and letting go of a certain 'subjectivity'—anonymity as a way to move from the singular to the common. In this process of becoming anonymous, the masks are used to conjure things into being. Each mask is intended for a different performance, and is imprinted with its own latent power.

Is decolonisation a driving force in your practice?

It very much is a driving force. We are thinking about decolonisation as the activation of new grounds from which to not be docile towards colonial time, narrative, and space. This is a very important position for us right now. In order to resist regimes of erasure, we need to not always begin from, or be bound within, colonial logic or language. That is what we are searching for. In that process, we point to the incomplete nature of the colonial project, and all that escapes its logic and domination, whilst being subjected to it.

With the masks, we were unfolding the connection between the archaic and the contemporary. As mentioned, the 3D-printed versions we use in the work are positioned in conversation with the black ski masks young Palestinians wear during demonstrations. But we also wanted to think about the masks in relation to destroyed villages, since it is in these villages that we come up against a very clear resonance and intersection. Through the colonial process, these destroyed sites are treated as fossilised sites that must remain in the dead time of history. In fact, some villages are being transformed into 'archaeological' sites, while others are cordoned off with barbed wire and signs that forbid entry. These acts of enclosure attempt to freeze and fossilise the sites; to transform them into a dead space of archaeological interest rather than living sites that can be reinhabited, whose buildings, land, and vegetation can almost be too easily rehabilitated back into the present tense. The activation of the site as a living fabric is one of constant anxiety for the colonial narrative that is concerned with the occupation of time itself.II We wanted to think about these potential sites of decolonisation in relation to one another, and in the work, the people making the trips to these sites use the masks to create new rituals, opening new understandings of what sort of performative powers the mask as a tool can have now.

One of the stanzas you use from Adrienne Rich's poem Diving into the Wreck reads: 'the thing I came for: the wreck and not the story of the wreck / the thing itself and not the myth'. Why is it important to come for the wreck and not for the myth of the wreck?

When we read 'Diving into the Wreck', it immediately resonated with us. In the poem, Rich is engaging with the materiality of the wreck and the very visceral, bodily experience of returning to it. For us, materiality and embodiment are extremely significant in a moment filled with bodily and material erasures. In many ways, the project—as with Rich's poem—is about these intersections between materiality and mediation, embodiment and disembodiment, thingness and virtuality. We wanted to think about the site of the destroyed village as a fabric and material that is not only witness to its own erasure, but is also resisting this erasure.

The video and installation focus on the natural environment of these sites: their presence, history, and texture. How did you experience being immersed in these overgrown environments? What did you discover?

In our returns to the sites, we discovered something incredible: each site has a living archive of vegetation that is resisting colonial erasure. Something in the very tissue of the site itself is undeniably living; it permeates from the soil into the stone and back into every bit of vegetation. There is a swarm of non-human life forces here, from insects to wild thorns and pomegranate trees, which are inscribed with the living memory and story of the site. It is here in the living archive of the vegetation itself that the site lives and breathes.

Most times, you cannot see the destroyed village unless you are really searching for it and even then it is very difficult to find—it has been obscured by pines or eucalyptus trees planted in the wake of destruction. The pine is not native to the area. The Israelis planted it mostly in the 1950s with such density that it radically transformed the land in many parts of the country. Many of the villages that were destroyed and depopulated were literally obscured by this new pine forest. The pine needles that drop from these trees suffocate a lot of the existing plants and trees, while the eucalyptus absorbs all the nutrients from the soil starving the other vegetation.

Despite these conditions, a significant amount of old vegetation somehow still exists, and often it is the glimpses of this vegetation—be it the cactus, the smell of wild fennel, or trails of wild asparagus—that actually leads you to the remains of these lost villages. Cactus was used to demarcate the borders of these villages and it is perhaps one of the most resilient life forces: the smallest bit of cactus can spawn whole new generations.

How do you use visual and auditory elements as storytelling devices in video?

Very often, we begin with a fragmented text that we have sampled from various writers, including ourselves. Both the video and sound are separately developed in relation to this text. Usually, we work on the sound before we work on the video, so the sound has a very strong, conceptual relationship to the text. Once we are working with the video, whether from existing material or material film, then we start reworking the sound and vice versa.

Initially, when we first started working together, we didn't feel that we could pick up the camera and film in Palestine. There were a lot of issues that needed to be problematised: namely the fact that images from Palestine had lost their potency. The repetition of the same images had almost taken the breath out of them; they were stagnating. At the same time, the situation on the ground was going through a kind of stagnation. We were stuck in the same discourses, but also literally stuck between checkpoints and walls. Our lines of vision had been quite literally obscured and occupied by the occupation. Our geographies would abruptly end when we reached a concrete wall and a sealed metal gate.

The military wall is not only a spatial tool of oppression, but a visual one. It severs the horizon of vision and, in that, the horizon of any futurity. So in many ways, working with the idea of the loop—with cyclical patterns, whilst clearly influenced by the practices of video art—very much resonated with our lived bodily experience in Palestine. You quite literally loop back into space in Palestine. In our videos, we are searching for breaks, fractures, and folds.

In this same period, we started looking at how colonial technologies had changed the soundscape, specifically how sound is instrumentalised to subjugate bodies and to create spatial structures; akind of psychogeography. Sound, far from being immaterial, is incredibly physical and tangible. We were interested in unpacking the relationship between sound, power, the body, and psychology, and sonic practices that actively circumvent these practices of power. The intersection between the body, space, and affect is crucial to how we have developed all our installations.

Our sound practice is also full of stutters and glitches in the same way that video is full ofbreaks and fractures. But in both, there is a sense of repetition and rhythm. So, despite there being a feeling of repetition, or looping backin on things, there is a rhythmic intensity that rises and ebbs. It is in this building of rhythm that we formally express the incomplete project of regimes of power and subjugation, and the possibility of being unbound.

In this same period, we started looking at how colonial technologies had changed the sound-scape, specifically how sound is instrumentalised to subjugate bodies and to create spatial structures; a kind of psycho-geography. Sound, far from being immaterial, is incredibly physical and tangible. We were interested in unpacking the relationship between sound, power, the body, and psychology, not to mention sonic practices that actively circumvent practices of power. The intersection between the body, space, and affect is crucial to the ways in which we have developed all our installations.

Our sound practice is also full of stutters and glitches in the same way that video is full of breaks and fractures. But in both, there is a sense of repetition and rhythm. So, despite there being a feeling of repetition, or looping back in on things, there is a rhythmic intensity that rises and ebbs. It is in this building of rhythm that we formally express the incomplete project of regimes of power and subjugation, and the possibility of being unbound.

My final question concerns the screenshots that feature heavily in And Yet My Mask is Powerful, both in the installation—pinned on boards, for example—or in the video, where they are laid one over the other. Could you talk about these?

Our practice is always positioned in the intersections and tensions between forms of physical and digital embodiment in a broad sense—embodiment of bodies but also things, ideas, and so on.

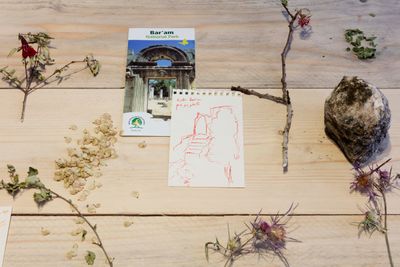

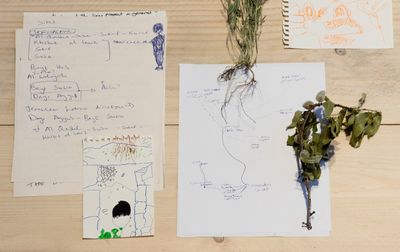

In our works, there is a constant movement of states of being between the physical, digital, and virtual. And as they move between these spaces, things mutate and accumulate. In And Yet My Mask is Powerful, screenshots are on screens; but tabs are also deconstructed as separate layers and pinned up on a board. 3D designs of Neolithic masks appear on screens, in print as images, and as realised objects. Extremely physical material traces from the destroyed villages are present in the form of plants, stones from the remains of houses, and garbage left behind by people visiting the sites—but they are being projected back into our digital desktop where various tabs are open, from video footage of the site to other research images and samples of text on the TextEdit app.

Crucially, these 'things' that unfold in the physical installation are activated in different ways by bodies in that space, as different readings or scripts are generated. The question that comes about for us is this: what is the relationship between the thing itself and its digital embodiments? And at the same time, what is the relationship between forms of physical and digital erasures to forms of disembodiment? This is when virtuality becomes important to us: it opens the space for a radically different projection of time that is not bound to the parameters of the immediately possible. It is about the relation between actuality and potentiality—what is and what could be.

But to speak more directly about the use of the screenshot: process is really significant for us and our process involves searching and thinking through a range of materials and concepts. In the process of unfolding materials—looking through them physically, digitally, and virtually—unscripted connections or potentials emerge. The screenshot became a way to capture unscripted moments taken as we were working through various applications, images, and texts on our computers. They would appear as layers creating intersections, densities, and disjunctures between research images, texts, algorithmic search results, and so on.

This method of working formally emerges out of a process of folding and unfolding temporal and historical layers, and drawing out the connections and ruptures between moments in the process. But this is also a way to open a space to project different potentialities. We are engaged in producing a non-linear reading of 'our' time that allows for a sense of multiplicity both conceptually and formally. This approach shapes the merging of digital, physical, and virtual realms in our work.

Perhaps just as equally significant in relation to this question is that, in this way of capturing material, there are always elements that cannot be fully seen or deciphered. So it is very much a dense story of erasures and reappearances, dispossessions and resistances. This is particularly formalised in the way in which images build or dissipate on top of each other, both digitally and materially. —[O]

I Nasser Abourahme, 'Returns without End: Ruin after Narrative', unpublished essay, 2017

II Ibid.