Clement Siatous and Paula Naughton

Clement Siatous was born in 1947 on the Chagos Islands, a small isolated archipelago in the middle of the Indian Ocean. He spent most of his childhood on the island of Diego Garcia until he and his family were forcibly evicted. The entire population of the islands was expelled by the British Government to make way for a US naval base in 1973. The base on Diego Garcia, also known as Camp Justice or Footprint of Freedom has become one of the most strategic, integral bases for the US global War on Terror and known as a transit site for CIA rendition exercises.

The UK Government has been accused of creating the fiction that a permanent population never existed on the Chagos Islands. This claim was made easier to uphold due to sparse photographic documentation that until recently mainly existed in dispersed military and government archives. As with many evicted Chagossians, compelled to leave their belongings behind, Siatous had no documentation of his heritage. In direct response to the continued political denial, he began to render a counterpoint to this official record.

Working with acrylic on canvas and employing vivid colour, Siatous illustrates his former everyday life in exhaustive detail, documenting the villages and homes of Chagos as well as its copra and fishing industries. The works in his new exhibition form part of a comprehensive chronicle of life on the islands.

Curator Paula Naughton, Director of Simon Preston Gallery in New York, started researching the tragic history of the Chagossians in 2010. To bear witness to this untold history she has developed a multi-media project called The New Atlantis

, which manoeuvres through testimonials and archival material obtained from a variety of sources, such as retired US Navy Seabees, military museums and WikiLeaks.

Clement Siatous’ solo exhibition at Simon Preston Gallery (which runs until 17 October) forms part of this on-going project and is the first solo exhibition of the artist’s work outside of Mauritius.

Ocula: How did this project start for you?

Paula Naughton: I have had a longstanding interest in the history of photography and previously worked on projects concerned with memory, migration and ideas of home, the journey away and the fallow space left behind. I first learned of the Chagos Islands during a conversation about generational and inherited memory when I was living in London. When I heard the horrendous history of the Chagos Islands, I was outraged that it had happened so recently. It sounded more like a shocking colonial act and I couldn’t comprehend that it was still happening to Chagossians today. I began to research the history of the Chagos Islands so I could understand how something like this could be enacted politically. It was then that I became aware that half of the Chagossian community were living in Crawley in the outskirts of London since the late 2000s. I contacted the Chagos Refugees Group and the project slowly began, evolving into a multi-media documentary project. I had no idea at the time what I was beginning and the journey it would take me on. The project has been led and formed by the relationships I have developed over the years. In particular by friendships with Olivier Bancoult, leader of the Chagos Refugees Group, and Marie Sabrina Jean, who represents the Chagos Refugees Group in the UK. And very fortunately, I met Clement Siatous whom I have begun to collaborate with on his important practice.

Clement Siatous, Sagren, 2015. Exhibition view, Simon Preston Gallery, New York. Image courtesy Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Can you tell me a bit about the title – The New Atlantis?

PN: The New Atlantis refers to Francis Bacon’s utopian novel about the future of human discovery and knowledge. Bacon, the 17th Century philosopher, played a role in colonising North America and the novel refers to the political ideologies of imperialism, colonialism, and overseas expansion. The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) was one of the last colonies Britain created as a result of Cold War policies. The US and UK further collaborated on military expansion as part of the global war on terror. Not only were the Chagossians forcibly evicted but for decades both the US and British governments denied their existence. There was an attempt to literally erase them and any record of their culture from history.

How did you meet Clement and how does his role fit into the wider ‘New Atlantis’ project?

PN: I began the project because I needed to understand what [happened] and how this could have happened and to create a visual narrative and history of the Islands. I felt that although serious momentum is finally building behind the Chagos Refugees Group campaign to return, I still could not see the community, as their voices were often lost behind news headlines. So initially I began recording testimonials from Chagossians, as an attempt to document their memories of life on Chagos and accounts of the deportation. It was during this process that I first became acquainted with Clement, five years ago now. I remember meeting him on a very dull overcast rainy day in Crawley, but through his paintings was transported to another place and time. Each canvas functions like a film-set, the story unravelling through the depictions. Until that point I had only heard through people’s accounts what life was like on the Chagos Islands, then in Clement’s paintings I could clearly see what so many people had described. For example, in the painting Dernier Voyage des Chagossiens a bord du Nordver anrade Diego Garcia, en 1973 the actual final deportation is illustrated in haunting detail. A difficult and emotional event to capture, [but] the painting manages to encapsulate the narrative of the eviction: the empty village lies behind a looming boat called the Nordver carrying distraught Chagossians, the naval personnel with their backs turned away, a metaphor for what was to come. Because the community did not have records to substantiate their right of belonging, Clement is acting as a radical historian in order to validate their history.

Chagossians use the Creole term, sagren, to describe their profound sorrow and longing to return to their homeland. A complex emotion to render, yet Clement encapsulates this and more through his work. As my research continued I gathered archive material from a variety of sources, including some previously unseen footage, showing the different processes of the copra industry. It was incredible to see how accurate Clement’s scenes were. In the very real actions of the US and British governments, they created a fiction that a population never existed. There was an attempt to defeat the population by silencing their voice. Through his memory and imagination, Clement’s paintings reveal an alternate ‘truth’. His works memorialise the memories of all Chagossians and in turn I hope the project can help contextualise his practice.

Is this project a political act and, in the wider fight that the Chagossians are undertaking with the British government, how do you hope this plays a role?

PN: My processes locate me in a creative space of duality, approaching the project through a bifocal lens, that of film-maker and curator. First and foremost, I hope the project can act as a visual record for the previously cloaked story of the Chagos Islands. The community’s entire existence has been one of defiance and resistance in order to claim their own heritage and to even call themselves Chagossian. Over the decades, against all odds, they have managed to rebuild their fractured community and network, and through this process are claiming back their voice and identity. Most of the archival photos and footage I collected were dispersed in government or military archives. Eschewing traditional narrative, I aim to merge fragments of material and memory to construct a history of the displaced individuals still affected today. I hope by sharing the images with the community, The New Atlantis can help give voice to their history and return these materials to the rightful custodians.

Clement Siatous, Sagren, 2015. Exhibition view, Simon Preston Gallery, New York. Image courtesy Simon Preston Gallery, New York

There is a hope that the Chagossians will return home. Would you say that Clement’s work provides an alternative archive of the Chagos Islands or would you say it points to the future of the islands?

PN: Clement and the community have a very realistic idea of what re-settlement will be like. They know life as they knew it on the islands can never be brought back again. Clement is creating an extensive chronicle of what life used to be like. Through this very act he brings to light what was stolen and expresses the paralysis of a community in limbo.

Clement’s exhibition, Sagren, comes at a crucial time. Both the US and UK Governments are under increased international pressure following a recent ruling by the United Nations that the UK government acted illegally in creating a marine reserve around the Chagos Islands. When the islands were originally leased by the US Government from the British, it was under a 50-year lease that expires next year. Additionally, in January a British Government study found no significant legal barriers to resettling the islands. There was a Supreme Court hearing that took place in London on June 22nd 2015 appealing a right of return, the results of which will be announced any day now. The British Government pre-empted this and proposed a re-settlement plan. Although this is momentous and an indicator that they are finally realising they can no longer ignore the Chagos community, it was not a moment of celebration as their proposed terms are akin to a modern day form of indentured labour. The community rejects these terms and we are all eagerly anticipating the result of the court hearing. Finally, after decades of fighting it feels that the British Government need to find a way to let them return.

I’m interested in photography as a tool that governs the appearance of statements or truths, particularly in light of the fiction that the British government fabricated in order to remove the Chagossians from their home. With this project, do you in any way reconfigure or interrogate these archival materials or do they stand singularly as testaments to what was and what happened? Also, could you tell me a bit about your own relationship to photography as a key to memory, truth, and lost realities?

PN: Through the process of collecting and editing, I have gathered the materials to illuminate a lost narrative. This curatorial exercise of rendering a story arc brings different images together through a confluence of voices. It is, however, not linear narrative that intrigues me. I’m interested in the asynchronous, the fragmental, and also the Rashomon effect of storytelling and the interpretation of these complexities. In Clement’s exhaustive body of work, he amalgamates memory and imagination, but in doing so he reveals more truths than any photographic image and has created a much needed physical body of evidence.

What are your plans for the project?

PN: The project will unfold in several chapters. The first chapter was the launch of The New Atlantis Project website (www.newatlantisproject.com), that I developed specifically to give Chagossians a forum to share and retain their collective history. The next chapter, Sagren, which I am particularly excited about, is Clement Siatous’ first solo exhibition outside Mauritius. The exhibition features just a small selection of his work as an introduction for a new audience. We are collaborating further on a publication of his extended practice as a chronicle of the Chagos Islands. It will be very interesting to see how the art world responds. I am also currently editing a documentary film weaving together a history of the Chagos Islands from the narratives exposed through my research.

Clement Siatous

Ocula: When did you start painting and why?

Clement Siatous: When I arrived in Mauritius I didn’t know that the Chagos Islands had been sold. I was 13 at that time and I was doing small drawings like all children do, and painting was not a serious thing for me. Then, between 1983-84, the British made a declaration that there were no indigenous people on Chagos and that no one had lived permanently on the island. It was at that point that I started painting in earnest, using my brushes to show that I come from Chagos, to shed light on what was there and what happened. At that time I was around 49 years old, and along with other fellow Chagossians, we decided to create a group to represent us, and we founded The Chagos Refugees Group. I had to think about our logo and I painted one with a basket, a knife and some other tools called piques that we used to remove the skin from the coconuts. And this started the process for me—drawing out the familiarities of our home and the things that we identified with, that made it home.

Before that I would paint occasionally, then after the British declaration, I started to paint more earnestly about the life and the history of Chagossians. Painting the logo for the group had made me more aware that my paintings were valuable in that they helped to show the truth, in the absence of any photographic records. When the logo went through the approval process and was made official by the Mauritian prime minister, he asked me what the origins were of the tools and if they came from South Africa. I responded that these tools were used by men and women living on Chagos in their daily work in the coconut fields. It was at that point that I really understood the power and importance of these paintings, of this record.

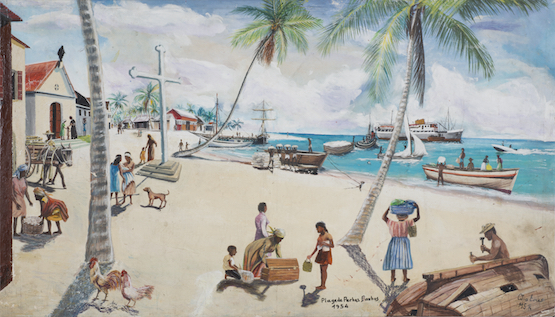

Clement Siatous, Ile Diamont, Groupe de Perhos Banhos, Chargement de Coco en 1955, 2001. Acrylic on linen, 26.25 x 45.75 in. / 66.7 x 116.2 cm. Image courtesy Simon Preston Gallery, New York

What process do you go through before starting a painting—for example, is there a research element and do you look at past paintings? Does photography play a role and do you own any photographs of home that you can reference?

CS: I do not have any of my own photographs from Chagos, not even of my family—all my paintings are born from my mind. I draw reference more from books that use rich colours, or photos of other places where the colours and subjects remind me of the islands—a seashore with a boat for example. I try my utmost to keep these details in my head.

Memory is selective—particularly since the invention of photography, which in some ways limits the way we remember the past and also, the way we archive and record truths. Without the influence of photography, memory is nonetheless selective, creating its own fictions in the process of recalling. The British Government used fiction to hide the truth about the residents of the Chagos islands, and in turn, you are using your imagination, or we could say fiction, combined with the facts to reconfigure and represent truths about life on the island. Perhaps these are influenced by the things you might have been told happened and have since reimagined for example. If we take the work Plage de Perhos Banhos, 1954, that was painted in 2012, can you talk me through how you access memory and what triggers you to paint a particular scene, set in a specific year?

CS: Yes, each and every painting starts from a specific memory that I have of what life on Chagos was like. As I mentioned, I don’t have any photos to reference. It was only more recently that I saw some images of Chagos. As I remember it, they were in black and white, with no colours. I didn’t use them because colours are very important to me, they represent the mood or essence of the islands. There are anomalies, for example, the painting R barkossion de copra sur la mer dans Diego Garcia originated from a photo I saw on Facebook (social media)—it was an image in black and white of a scene at the dock. But for me the image was incomplete – it did not tell the whole story. I added some more people, the coconuts, the fish and so on, to give people a sense of the whole history, and then I also painted in the plantation managers completing some of their responsibilities, as this job was guided by managers. I added in the background, a view of Diego Garcia, to show where the boat was, which was not on the original photo, to let people know exactly where on the islands the boat would have been. The original photo had just one man working. The English flag was not so visible in the photo but I painted it clearly because the boat was under the charge of the English government—proof that the island would soon close.

Clement Siatous, Perhos Banhos Boderor 1944, 2015. Acrylic on linen, 27.5 x 58 in. / 69.8 x 147.3 cm. Image courtesy Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Do you draw from the memories of the community as a whole or do you draw from your own memories only?

CS: I place myself within my memories but I also try to capture all our memories, and those of other Chagossians and the details they tell me. It is important when I look at the painting, especially when I see how the people are working, that it reminds me about my island and our lives then. I don’t know if there will ever be Chagossians on the island again or if it will re-open, and we can never have the life which we have lost, but with the pictures I make they cannot be taken from us. That’s why I paint.

Can you tell me a bit more about your plans for the work—is there a particular inventory of scenes that you will paint and why are these scenes important?

CS: There are many, many more paintings I plan to complete, more memories and details from Chagos that I want to capture. I have yet to paint all the 32 different jobs which we were responsible for on the islands. I plan one new series, about 15 paintings—the title is Batte la boue pour faire la corde coco—in order to complete the series. This will include more social activities—the sega parties and dancing, the toys we had, and many more, which become clearer and materialise as I paint.

Each one of my paintings is a political act, showing my anger to the British Government as they continually stated there was no one living on the islands. We have had many difficulties, some of the community even with regards to their passports. After deportation, any Chagossian who tried to get their birth certificate, stating place of birth, was denied. The Mauritian government had no records of births as they were Chagossian, but as it was now owned by the British, there were no birth certificates to issue. It could have been brought to the courts, but most of us had no money to do this. A large group was deported to the Seychelles, so many went there to try and register. But, there was still no record and so they had to gather testimonials from family. It took a number of years just to claim a record of their birthplace—this denial is a denial of our human rights and this body of work is my contribution to the Chagossian fight. I see these paintings as legal proof that we are from the Chagos Islands.

Your works look like sets to a film perhaps or scenes from an ongoing visual story; there are many pockets of activity and there is always some kind of action or conversation. Can you tell me a bit about that, about perhaps the influence of film or graphic novels?

CS: When I was a child, I loved to look at different comic books and also any books I could find about American Hollywood movies. The stories of the wild-west, the cowboys, and the Indians that would fight the Americans. Like Elvis Presley in Flaming Star, The Battle at Apache Pass and John Wayne. I always liked to see how they created the mountains for the sets and I would draw the wooden houses. But I don’t think about film when I paint. I focus on the story that I am trying to show, adding in details until there are several layers of stories occurring, lots of different characters, until the scene is as full as a scene from a film, until it conjures the bustling life on our islands.

Clement Siatous, Plage de Perhos Berhos, 1954, 2001. Acrylic on linen, 25.25 x 44 in. / 64.2 x 111.8 cm. Image courtesy Simon Preston Gallery, New York

You pick very particular times of day, and also specific dates for the pieces—why are these important and what is the relevance of these dates?

CS: When I am painting, for example if I am working on a face, I concentrate only on one thing. There are at least 20 steps that I go through, starting at the far end, and working forward through the layers of perspective. For example, with Salamon Bordero pilser coco fam la batin 1945, I set the date as a way of providing more historical context for the viewer. 1945 is before I was born but there were generations before me that had lived on the islands and as these paintings work as a record, I felt it important to push back in time.

The paintings have become more and more complex with time. There is a lot more activity and play on light and dark. To provide another stream of historical accuracy, I take into consideration the time the scene would have taken place—for example, if a regular activity would normally happen at noon, the sun should push the shade beneath our feet. The water is also a clue to the time, as it changes depending on where the sun is—from blue, to red, to sparkles of light when the sun is overhead. The shading has become as important as colour, bringing the scenes to life, setting a time and a place that is very specific and undeniable fact.

I guess in this way, they reference film or the documentary photography that you mentioned you used to like growing up. But really, they belong to a more traditional way of recording or archiving—a process or method that pre-dates photography.

CS: Yes, one that relies on our imaginations and our ability to re-interpret this into something that can be shared. For me it is a way to tell our story. —[O]