Dane Mitchell: ‘Entanglements occur in a state of reciprocity’

Dane Mitchell. Courtesy Creative New Zealand. Photo: David Straight.

Dane Mitchell. Courtesy Creative New Zealand. Photo: David Straight.

While it is not unexpected to find an artist making work about 'the invisible' in a time after the post-internet and post-conceptual art moments, there are few artists who make this their trajectory. Dane Mitchell, based in Aotearoa New Zealand, has engaged with unseen phenomena, bringing what is on the air, perceptible to the senses, or only imagined to our notice. In this way, Mitchell's work inverts the qualities of conceptual art, its history of concentrating on the thingness of objects, or the theatricality of their performative relations in space. Instead, objects demarcate the possibility of their own agency by means of ideas that are outside conventional Western thinking.

A recent example of his practice was the exhibition Iris, Iris, Iris at Mori Art Museum in Tokyo (18 November 2017–1 April 2018) and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (1 September 2018–24 February 2019). Drawing on research undertaken in Japan into historical spirit figures and traditions engaging with vapours and atmospheres, Mitchell worked with experts in headspace technology as well as makers of traditional incense to create an elegant connection around the fragrance of the iris flower, cultural and industrial applications of the iris, and the role of the iris in the body.

Mitchell was Aotearoa New Zealand's artist at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019, where he premiered Post hoc, an installation employing mass technology to disperse a corpus of nothingness. Invisible waves of sound carrying a litany of losses were transmitted across locations in Venice by the mysterious symbol of this project—cell towers badly disguised as pine trees. The project is a contrast to the sparseness of many of his previous installations, such as Indwelling at the 2016 Biennale of Sydney, where a homeopathic remedy for both forgetting and remembering was dispersed, or Fourfold Threshold in the Encounters sector of Art Basel Hong Kong 2015, where unseen forces were summoned by a 'villain hitter'—a practitioner of sorcery specific to Hong Kong.

In this conversation, Mitchell talks to Dr Zara Stanhope, curatorial manager of Asian and Pacific Art at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and lead curator for Post hoc, about the intentions behind his practice, how Post hoc expands on ideas of conceptual art, and where the project has taken his thinking.

ZSWhat are your aspirations as an artist? What is the aim for your work in the larger sense?

DMI'd hazard to guess that I'm interested in structures that attune the world. I think my long-lasting fascination in thresholds of visibility stems from an interest in what sits just out of view in our encounters with, and experiences of, the material world, forms of knowledge, and belief. Much of what I do is concerned with the physical properties of the intangible as well as the visible manifestations of unseen structures of many kinds. I think that I seek to tease out the potential for objects and ideas to appear and disappear.

ZSYour desire often leads to encounters that are outside viewers' spheres of experience. Audiences are placed in the presence of spells, liquids, vapours, or materials such as obsidian that are credited with special properties or have undergone processes connected with a fringe science like homeopathy. These experiences that lack rational evidence lie on the edge of common understanding. Two homeopathic substances were said to simultaneously enable remembering and forgetting for Indwelling, presented at the Biennale of Sydney in 2016. You set high expectations in requiring viewers to engage with projects in good faith.

DMMy work attempts to be dynamic in activating the spaces between substances, images, and the body. In this way, the work might become more than the sum of its parts. Elements continue to synthesise internally, within the work itself, and externally, within the viewer, opening up a complex network of possible interactions. Much of this is due to employing liminal, near-invisible materials that are sometimes unknowable, such as my use of dust in Dust Archive (2003–ongoing); perfume, as in Let us take the air (2015); and sorcery, as in Celestial Fields (2012/2017). The experience of such material at the limits of perception heightens awareness, mental analysis, and our proclivity for asking questions about what we see, know, and experience.

Some of these artworks I think of as being viscous, in the space where images, responses, ideas, memory, and feelings interact. Viscosity is a certain kind of medium, one that is elastic and sticky, the experience of which I liken to the metaphor described by Merleau-Ponty as 'being honeyed'.

ZSThe idea of needing to have faith or entering into a space containing the qualities of both certainty and skepticism separate your practice from much conceptual art. How do you know how far to push the boundaries of belief?

DMI really like this difference you point to, as I am interested in the possibilities of enriched histories. I'd liken the idea of the mutuality of certainty and skepticism to that of the space between revelation and concealment. My work potentially gains some agency by disguising process, working with chimerical images, confusing the location of a sensation, folding immateriality into the material and the imagined into the perceived, or by invoking the microscopic.

I'm also really drawn to the idea of 'uncontrolled seeing', which to my mind is only possible when you entangle certainty and skepticism at once. There is evidence of the possibility and impossibility of capturing the spoken word in glass in A Guest, A Host (2008), where I spoke directly into molten glass to give tangible form to voice. In another example, the possibility and impossibility of creating an olfactory vacuum is realised in Smell of an Empty Space (Vaporised) (2009), in which a unique scent is diffused in an attempt to replicate the smell of an empty space or a 'terrestrial impossibility', for when we call a space empty it is merely a convention for describing a space that is filled with something unacknowledged. In Celestial Fields (2012), I explored the possibility and impossibility of making an audio recording of the present. Fifty-two records—one for each week of the calendar year—contain a single locked groove on the outer parameter, which repeats the word 'now' in my own voice ad infinitum.

ZSYou have addressed many ideas of physical and conceptual thresholds and what lies beyond them—spiritual, alchemical, mythical notions and ideas to do with the body as well as earthly phenomena. These have required many types of collaboration with experts in other fields including a shaman and a perfumer. Can you talk a little about your process in navigating from an idea, through the research to determine the final outcome of a work?

DMThere isn't a single methodological approach to my making. However, working with specialists interests me a great deal as it enlivens the production of work and leads me in unexpected directions. These are entangled relations rather than collaborations, as they are complicated by my authorship. Mostly I am searching for technical expertise: for example, in Iris Iris Iris (2017–2018), I did not know how to operate nor read the data generated by the headspace technology used by the scientists who I worked with at the company Takasago in Japan. Their expertise enabled the capture of the aroma molecules rising from three sources: an iris flower, the iris of a camera lens, and the scent of a paper umbrella—made by yet another specialist—that matched the colour of my own iris, resulting in the production of a new fragrance from the combination of all three.

There isn't a single methodological approach to my making. However, working with specialists interests me a great deal as it enlivens the production of work and leads me in unexpected directions.

These entanglements occur in a state of reciprocity between myself and the specialist in the same way that reciprocity occurs between the artist and an idea, and ultimately the viewer and the work. Working with others is never transparent and always full of complexity and unknowns, so often I have very little sense of where this methodology may take me.

ZSYour recent project for the 58th Venice Biennale, Post hoc, required working with experts in diverse fields. Air was also a key medium, this time for carrying sound. However, Post hoc is distinct in your practice in repurposing some fairly lumpen cell towers that were industrially produced and designed to be disguised as trees, which was far from the usual elegance in the aesthetics of your materials. Viewers could use wi-fi to tune into hundreds of lists of phenomena that have disappeared or been lost. It was a perfect pairing of synthetic nature with digital industry. How did you come to join the camouflaged, prosaic cell towers with the extensive data you compiled in your personal selection of lost phenomena?

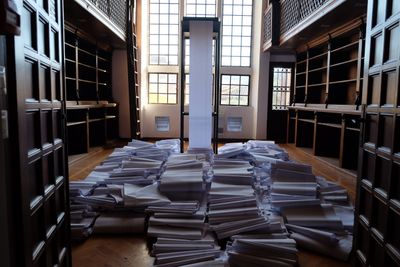

DMPost hoc is made up of three concise forms: a chamber, a printer, and seven cell tower trees. Each is part of a network with interlocking yet discreet roles. The anechoic chamber, where the voice or utterance originates, named each entity only once over the seven months that the project was showing. The chamber can be thought of as the generative heart of the work. The printer was located in a deliberately emptied library, where the utterances slowly fill the room, printed on an abundance of unfurling, looping paper. This could be considered the moment of materialisation, where over three million words are printed on around 20 kilometres of paper in sync with the announcement in the chamber.

The seven 'stealth cell trees' are based on infrastructure developed in the 1980s to disguise the communication towers that increasingly populate our built and natural landscape, 'infecting' it with transmitted signals. The stealth cell trees—or 'frankenpines'—ask some fascinating sculptural questions before we even consider their functionality. They raise interesting questions around whether a radio wave or wi-fi signal can be considered an object, let alone a sculptural one. The cell trees also challenge the aesthetics of mimicry and representation, which lie at the historical foundation of art history. They are undoubtedly troublesome forms. In fact, I think there is something antagonistic about the towers, in the way they displace and replace nature at nature's expense, and how they operate as grit in my own aesthetic logic. They are uneasy in both their origin and outcome.

ZSAlthough the cell tower trees are poor replicas of pines, they also seemed to settle into their surroundings in Venice, only becoming visible if viewers were sufficiently close for their industrial nature to become apparent.

DMIt's interesting the way you describe the trees as settling into their surroundings in Venice. I didn't expect that, because in their attempt to go unseen they do the opposite in many respects. And yet I think you're right to say they settled in or perhaps their incongruous and uncanny 'nature' drew Venice towards them. They somehow showed Venice to be more like them than I had anticipated; a construction or set of façades presenting our expectations of Venice back to us.

ZSWhat were your hopes for Post hoc and did you think that they were realised? I envisioned that viewers who unexpectedly came across a solitary tree and selected some lists to listen to would have a different experience to those who came to the main site with its multiple components. Did unexpected outcomes arise from this ambitious project?

DMMy hopes were that Post hoc would be experienced as complex and richly layered. To my mind the work could be experienced in any order and reveal the density and ungraspability of those past, withdrawn, and disappeared entities—spoken and printed—that sit at the centre of the work. The network extended to the northern, southern, western, and eastern edges of Venice, producing a thin, horizontal field of transmission across the city from which the lists can be downloaded and plucked from the air. These 'frankenpines' were either stumbled upon or sought out and although unnecessary to see all sites, each offered a distinct experience of both the city and the work. I've heard stories of meetings under the trees between people travelling for the Biennale and local Venetians who on one account, shared headphones to listen to the list of vanished languages, and heard multiple accounts of discoveries of parts of the city otherwise not visited, such as the internal courtyard at the public hospital, which has its own resident population of cats.

ZSPost hoc heightens the duality of simultaneous possibility and impossibility. The artificial voice in the anechoic chamber read out the hundreds of lists over the duration of the Biennale, but the walls totally absorbed the sound! In compiling the millions of invisible, passed, or destroyed phenomena, you also acted as a provisional anthropologist or historian. The lists were highly subjective, and you have talked about the voice 'conjuring up or calling forth' the information, yet the lists formed a type of poignant and poetic open-ended archive. Do you envisage continuing the kind of archival documentation that was at the heart of Post hoc in future works? What's on your mind now?

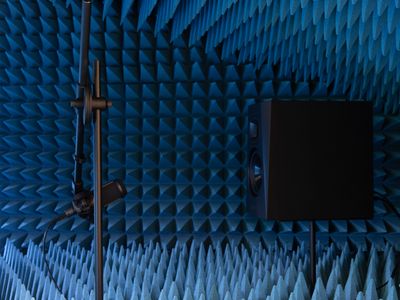

DMThe tapered anechoic chamber in which the list is generated and transmitted might appear uncommunicative, in that the voice cannot be heard from the outside, but you do experience this voice transmitted by the cell trees. The speaker and microphone visible through the windows into the grotto-like interior of the chamber seemed to me to be a very simple means of suggesting the acts of speaking and listening—importantly, in this work, by a non-human entity. The chamber has some incredibly beautiful properties. Tapered anechoic chambers are used to test fields of electromagnetic transmission, such as that from an antenna. The chamber replicates an unimpeded space stretching to an infinite horizon, enabling a perfect sound wave. It's akin to dropping a pebble into a still body of water without edges. It's not so much that the chamber absorbs the sound, as it allows it to move freely beyond the visible edges of the form.

In the same way, the list is ungraspable as an experience; it is a colossal language-object, and no one viewer or listener can comprehend it, given it reads continuously for months on end. The task I set myself is similarly ungraspable. Post hoc seeks to push up hard against Western epistemology: it confronts the impossible task of holding the weight of the world in encyclopaedic form. The project scratches the poetic surface of all that which is gone—that's all it can ever do. However, it does give some sense of the sheer magnitude of this material. It also suggests that what we are left with is data, and in many respects, it is through data that we experience the material world today. It's also important, and probably timely, that we reflect on how we got to this condition of leaving so much in our wake, given that the present and future are predicated on obsolescence and loss.

Post hoc seeks to push up hard against Western epistemology: it confronts the impossible task of holding the weight of the world in encyclopaedic form.

What's on my mind now? My thoughts are still inside Post hoc. Making and compiling the lists themselves has been illuminating, and there are ways I'm thinking about extending elements of this data into the work. I'm keen to see what else they might make appear and disappear. —[O]