From Mardi Gras to Maralinga: the Sydney Biennale’s Highs and Lows

Front to back: Citra Sasmita; Mangala Bai Maravi. Exhibition view: 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, Chau Chak Wing Museum (9 March–10 June 2024). Commissioned by UOB for Children Art Space MACAN Museum Jakarta, Indonesia 2020. Courtesy the artist and Yeo Workshop, Singapore; Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney and the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain. Courtesy the Baiga Tribe. Artist Assistant: Amit Arjel-Sharma. Photo: David James.

Curated by Cosmin Costinas and Inti Guerrero, the 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns (9 March–10 June 2024), illuminates life on Earth as a mesh of experiences and worldviews, with works by 96 artists and collectives from 50 countries and territories.

'The singular life-giving body that is the sun, like the world it shines light upon, has otherwise been known under thousands of different words in as many languages,' states the curatorial text's opening lines, specifying that 'each name carries a different cultural viewpoint'.

Köken Ergun's multi-channel video installation HEROES, DEAD, TOURISM (2024) diagrams this difference at the UNSW Galleries, by looking at how guided tours of Turkiye's Gallipoli peninsula, where the World War I Gallipoli Campaign was fought between Entente and Ottoman forces, are modified to suit different audiences.

One guide focuses on stories of Australian and New Zealand soldiers for visitors from those countries, given the establishment of Anzac Day following the campaign. While a guide speaking to a Turkish group describes 'the enemy' entering the strait with 200 ships, emphasising the Ottoman victory over a foreign invasion.

Divergent commonalities emerge from these oppositions. In one interview with a New Zealander, Ergun establishes that the concepts of martyr and hero are equivalent in the context of war.

Fraught confluences like these electrify Ten Thousand Suns, where charged harmonies arise out of resonant differences and uncanny inversions. This is especially the case at Chau Chak Wing Museum, where Choy Ka Fai's single-channel video Exodus (2024) explores the histories of the Indonesian folk dance Dolalak and Indo-Rock.

Dolalak, where dancers wear Dutch military-style uniform while performing Javanese dance, apparently originated when inebriated Dutch soldiers were spied dancing by a campfire in the early 20th century. Indo-Rock emerged among Indonesian exiles in the Netherlands after World War II, following a failed Dutch attempt to recapture Indonesia, with bands like The Tielman Brothers fusing Western, Indonesian, and Kroncong music styles.

In a series of music videos, Exodus shows the Dewi Arum Girls, social media stars who perform Dolalak to Indonesian Pop, dancing to remixes of Tielman Brothers songs by musical project Raja Kirik with vocalist Silir Wangi. Among the tracks is 'Wanderer without Destination', released in 1966, whose title seems to describe not only the life of exiles but of cultures caught in the hybrid flux of historical and colonial space-time.

A voice seeping into the room where Exodus is screened amplifies that unsettled restlessness. It belongs to Chemehuevi and Anishinaabe poet Diane Burns, who is seen walking the rundown streets of New York's Lower East Side in a 1988 video projected onto a large wall at the gallery's entrance.

Named after the poem Burns recites on film, Alphabet City Serenade shows the artist raging at the gentrification of the same neighbourhood that Martin Wong, whose paintings are on view in the gallery, immortalised on canvas; before describing herself as a 'hopeful Aborigine trying to find a place to be' and proclaiming her hatred of the United States.

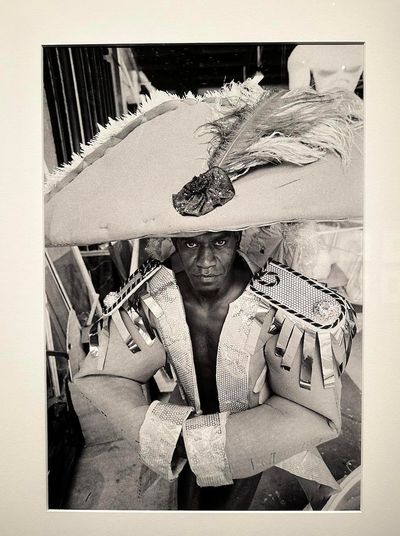

It's a complex indictment. Burns is an Indigenous American powerfully protesting an ongoing transgenerational occupation by speaking in its language. In the same gallery, a black-and-white photograph taken by Elizabeth Dobbie in 1988, the same year Alphabet City Serenade was filmed, shows Aboriginal and South Sea Islander dancer Malcolm Cole, dressed as Captain James Cook to recreate his fleet's landing at Botany Bay in 1770, for Sydney's Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade, on the year of Australia's bicentenary.

Cole, the first Indigenous Australian to host a Mardi Gras float, appears in another set of photographs in the gallery. Taken by Chinese-Australian photographer William Yang, they show workshops and performances by the Aboriginal Islander Skills Development Scheme (AISDS) and its student ensemble AIDT (Aboriginal/Islander Dance Theatre), later the NAISDA dance college, established in 1976 by Black American dancer Carole Y. Johnson.

Cole and Yang are monumental presences in Ten Thousand Suns. At the UNSW Galleries, Yang's 'My Uncle's Murder' series (2008) comprises annotated photographs recounting the 1922 murder of William Fang Yuen by the white manager of his cane plantation in Queensland, home to a historic Chinese diaspora.

The final image shows a court transcript signed by Yang's mother, who gave evidence at the trial where the accused was acquitted—something that, as Yang notes, the Chinese community saw as an injustice. 'I feel that the legacy of this murder came down to me,' he writes on the print; 'while I was growing up, my ethnicity was suppressed.'

The suppression of one's identity to survive white supremacy, whether by choice or force—the latter expressed in the gallery by drawings from the 1940s created by children forced to reside in the Carrolup Native Settlement as part of the Australian state's racist assimilation policies—is recuperated in 'My Uncle's Murder' through the archiving of a historic transgression for public view. In one image, Yang stands in front of tall canes and stares defiantly into the camera, maintaining a vigilant distance.

That vigilance, however, transforms in Yang's black-and-white photographs that have been blown up and digitised into a three-channel projection at White Bay Power Station, a much-hyped Biennale venue that has been closed to the public for over 100 years. Taken in 1976, images show AIDT dancers—Lillian Crombie, Michael Leslie, Wayne Nicol, Richard Talonga, and Roslyn Watson—ahead of their trip to Nigeria for FESTAC '77, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, attended by figures like Audre Lorde and Miriam Makeba.

Yang's gaze is present, open, and full of admiration for his subjects. The movement for Indigenous rights in Australia was gaining traction at the time, as global decolonisation movements strengthened transnational solidarities across struggles, and the dancers exude a confident promise in their intimate interactions.

Elsewhere in the White Bay Power Station, a giant colour mural by Yuwi, Torres Strait and South Sea Islander artist Dylan Mooney shows Malcolm Cole dressed as Captain Cook with a rainbow curling around him.

Nearby, a video by Panos Couros, Cole's Mardi Gras collaborator, shows Cole on his parade float. It's a luminous moment that Yangamini, a guerrilla collective of Tiwi sistagirls and their accomplices, participated in recreating by developing the Sydney Biennale's float for its first ever participation in a Mardi Gras parade in 2024, with Cole's twin brother, Robert, taking on the role of Captain Cook.

The Sydney Biennale's presence at Mardi Gras certainly fit the context of Ten Thousand Suns, which emphasises celebration in the face of colonial apocalypse. Particularly given the exhibition's necessary exaltation of Aboriginal pioneers like Malcolm Cole and their allies, in the aftermath of the 2023 Australian referendum that failed to enshrine the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice in the Australian Constitution.

That 2023 referendum highlighted the ongoing struggle for justice in the context of a settler colonial regime, and the gap between acknowledgment and action that Yangamini's installation at the UNSW Galleries, Mapurtiti Nonga (Evil Ass Dreaming) (2024), protests.

A video and a series of giant, sculptural butt plugs made from materials local to the Tiwi Islands, draw attention to a pipeline the Santos oil and gas company is constructing in the Timor Sea and the Australian Federal Court's recent dismissal of a legal challenge by Tiwi Islanders against it. In the video, interviews with Larrakia and Tiwi Elders and Yangamini members rail at the land's exploitation and the lack of consultation with its Traditional Owners.

Yangamini's butt plugs, in this context, refer to Mapurtiti Nonga, a spirit whose mouth is likened to an anus spewing toxic gas. They have been designed to block the hot air of extractive corporations and the words that they and their political accomplices use to justify their actions.

Ten Thousand Suns is not immune to such hot air, with its emphasis on celebration sometimes lacking the space to reflect on the militant, activist roots of joyful resistance in the context of continuing struggles. Take the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) exhibition. This is the only instance in the show where the curatorial wall text references the atomic bomb, whose blast was likened to the radiance of a thousand suns by its inventor J. Robert Oppenheimer, quoting the Bhagavad Gita, as part of the Ten Thousand Suns theme.

The introduction describes the colonial history of atomic testing across Indigenous lands and seas—including at Maralinga, South Australia, where British nuclear tests from 1956 to 1963 caused irreparable harm—before calling for political joy within two paragraphs.

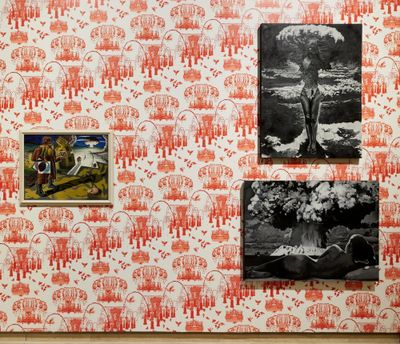

The connection between atomic catastrophe and the sun's luminous ability to connect peoples and places is potent, but the exhibition does little to expand this premise beyond one room at AGNSW, which is overloaded with works depicting mushroom clouds. Walls are covered with Saule Dyussenbina's wallpaper, Achievements of National Economy, Fountain of Friendship of Peoples of the USSR (Moscow, Russia) (2023): red plumes bursting out of The Friendship of Peoples Fountain in Moscow reference the Soviet Union's nuclear tests in Kazakhstan between 1946 and 1986.

Or perhaps these leaps from Mardi Gras to Maralinga, as one curator put it, feed into the position that Ten Thousand Suns leans into, where celebration functions as an unequivocal rejection of colonialism's apocalyptic violence...

After this section, there's scant mention of the atomic bomb or power until one reads the text for a series of stunning paintings of brilliant skies by Segar Passi at the Museum of Contemporary Art, which cautions viewers not to interpret russet-backed clouds as explosions. Nearby, Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg's masterful, looped single-channel video Doomed (2007), stitches explosive scenes from Hollywood disaster movies into a tragicomic portrayal of Western modernity's incessant death drive.

Then there's Peter Minshall's 1985 video, The Adoration of Hiroshima, which is shown on three screens arranged vertically in one corner of White Bay Power Station. Footage shows Minshall's participation in the 1985 Trinidad Carnival wearing an atomic mushroom cloud of ostrich feathers, which expanded into a procession in August that year at an antinuclear protest march in Washington D.C. on the 40th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing.

While there's a powerful connection between Minshall's embodiment of the atomic bomb and Malcolm Cole's cosplay as Captain Cook, the lack of engagement with these potent and complicated gestures of overidentification, which highlight colonialism's complex impact on bodies and souls, feels like a missed opportunity.

Or perhaps these leaps from Mardi Gras to Maralinga, as one curator put it, feed into the position that Ten Thousand Suns leans into, where celebration functions as an unequivocal rejection of colonialism's apocalyptic violence altogether.

Nowhere is this more effective than in Yankunytjatjara artist Kaylene Whiskey's giant TV installation at White Bay Power Station, Kaylene TV (2023), populated by human-size cut-outs of pop culture figures like Dolly Parton and Whiskey's hybrid Black superheroes, kungka kunpu (strong women).

Illuminated by fairy lights, the TV's candy-blue-walled interior features, among other things, posters of pop icons like Tina Turner and David Bowie, alongside paintings of the Aboriginal flag in a heart shape. An audio recording of Whiskey's voice blends different lyrics. 'We don't need another hero ... I'll be your hero,' Whiskey proclaims before singing lines from Whitney Houston's 1987 hit about dancing with somebody who loves you.

It's a powerful invitation, to lead with love. And based on mainstream reviews, the strategy has succeeded, with critics lauding a vibrant, diverse, and beautifully installed Biennale that calls people in rather than out. And truly, Ten Thousand Suns is a stunning show.

Highlights include Pauline and Jim Yearbury's wood panels (c.1967–1975) carved with the forms of Māori gods; I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih's vibrant, minimalist paintings of contorted bodies from the late 1990s and early 2000s; Citra Sasmita's acrylic on Kamasan scrolls from the 'Timur Merah Project' series (2019–ongoing), depicting Balinese women as decolonial agents; Sana Shahmuradova Tanska's haunting unstretched oil on canvas depictions of spectral bodies, created amid Russia's invasion of Ukraine; and Udeido Collective's powerful installation The Koreri Transformation (2024), with the walls of one room painted with scenes referring to the West Papuan struggle for sovereignty and rights.

Yet amid such galvanising highs, it was hard to ignore murmurs from exhibition participants and their associates lamenting uneven artist fees, communication, and support, which highlights issues of scale and sustainability for biennials like this, not to mention cultural funding and management in general. Of course, these issues are not unique; across the art world, proclamations of care have yet to translate into structural transformation. —[O]