Hoda Afshar's Fragments of Reality

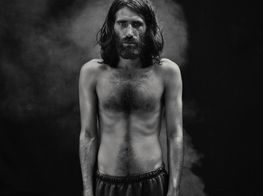

Hoda Afshar. Courtesy the artist.

Hoda Afshar. Courtesy the artist.

In the traumatic and epoch-defining events of the last three years, some of which include raging bushfires and floods, a pandemic, global conflicts, and the recent women-led revolution in Iran, the Melbourne-based Iranian artist Hoda Afshar has explored human folly, cruelty, and frailty, but also bravery, resistance, and endurance.

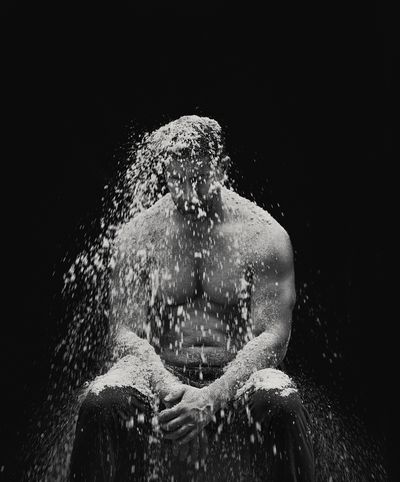

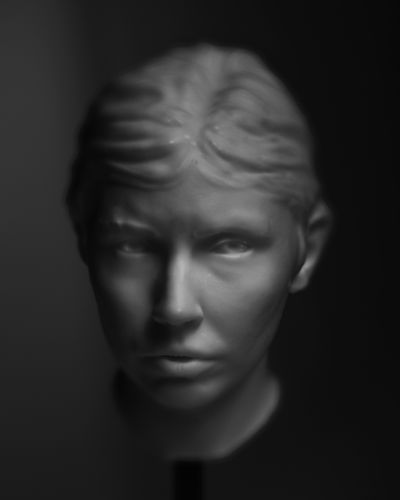

Works such as Agonistes (2020), which includes video and photographic portraits, highlight human narratives through the testaments of whistleblowers from within Australian security industries, including its offshore detention system, youth detention facilities, intelligence services, and other state agencies.

In doing so, Afshar eulogises their bravery in speaking out, and precisely and poignantly throws a spotlight on the undocumented lives of their charges—refugees, teenage prisoners, and those whose consciences will not allow them to stay quiet.

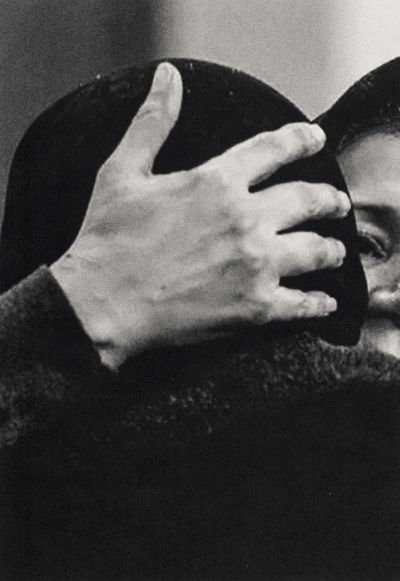

Another video and photographic series, Remain (2018), also gives voice to the voiceless. The narrative tracks through the 'paradise' of beaches and jungles on Manus Island, where asylum seekers are held in Australian government immigration detention—one of whom is the writer and journalist Behrouz Boochani, who now resides in New Zealand.

Boochani famously penned his autobiographical account No Friend But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison (2018) via WhatsApp messages, several hundred words at a time, to an editor in Melbourne. The book went on to win the 2019 Victorian Premier's Prize for Non-fiction.

Afshar's background as a documentary photographer informs in her visual art practice. For Afshar, documenting the seen is a powerful act, but illuminating the unseen, absent, or missing is the real art.

Whether making visible an anonymous Instagram protestor in Iran, or detailing the lives of detainees on Manus Island, Afshar's practice is about changing the narrative.

In co-opting the documentary genre, Afshar harnesses its truth-telling power while simultaneously telling another story—one that is often unspoken or at odds with what we are told by those in power.

Afshar is currently working on projects for The National 4: Australian Art Now (24 March–23 July 2023) in Sydney; Sharjah Biennial (15 February–11 June 2023); and the TarraWarra Biennial (1 April–16 July 2023) in Victoria, Australia.

SAThe ongoing women-led protests in Iran following the death of Mahsa Amini in the custody of the morality police are the focus of your installation, Women, Life, Freedom, commissioned by the MuseumsQuartier Wien in late 2022. How has your practice been shaped by the events of the past few years?

HAI started making Aura, my work for the upcoming exhibition The National 4 in Sydney, in Melbourne in 2020 during the Covid lockdowns. I collected images online during the Australian bushfires of 2019 to 2020. These events were so extreme, and it was quite shocking to me that although we only experienced them online, rather than physically, they affected us greatly.

After the peak of the bushfires, the pandemic arrived in Iran. Around the same time, I woke up to news of Donald Trump tweeting that he was going to bomb 52 sites in Iran, including important cultural sites. Panicking, I called my family and begged them to leave the country. Then the pandemic arrived in Australia; the killing of George Floyd happened; then Black Lives Matter; the bombing of Palestine. The images were quite suffocating, involving burning and fire, death, smoke, and fog.

Aura features tiny, zoomed-in fragments of much larger photographs—images that have really stayed with and affected me. In thinking about the psychological impact of these photographs, I am trying to create a dialogue between images of crises that we experience through the black screen of mobile phones.

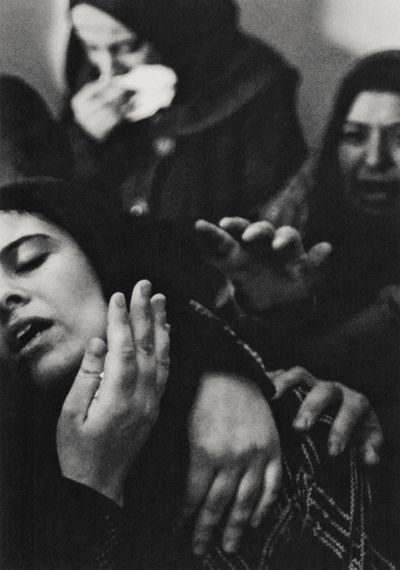

Women, Life, Freedom looks at images on social media and other online platforms. I'm interested in how images of this women-led revolution are different from those of past revolutions. In looking at the visual language of image-makers on the streets, how they use it in ways that demand attention, you can see it's performative. It's for the camera, for the world to see.

For instance, the way women stand holding their scarves up with fire behind them—these theatrical gestures are documented by anonymous photographers. It's not about the authorship of the image, but rather the purpose of the image and what it's capable of doing—in a post, on social media, and so on. There's so much poetry in these images. There are traces of women all over them.

SAWhat is the impact on us—of experiencing these events through social media and on our mobile phones, with all of the immediate coverage we are exposed to?

HAI think these extreme events have always happened, but now we're exposed to them all at the same time, leading to overwhelming feelings of desperation and helplessness. In a way, the more exposure there is, the less sense we have of being able to actually influence the world. The work is a response to that.

For another work for The National, Undone (2023), I collected online footage of bombings that have taken place around the world during the last decade. As I discovered, there are currently more than 40 armed conflicts happening in the world.

I recorded news footage on my mobile phone, then reproduced them in black-and-white and zoomed in on the scenes. The accompanying audio is the sound of various heartbeats I collected online. These change in pace and rhythm, and the footage is shown in reverse. Gradually, you see demolished buildings standing up again. The heartbeat gets faster, and you are taken inside to look through the window at the bombings. The work is about the desire to undo war and imagine a different outcome through these images.

SAThere is a sense of history repeating itself, insofar as the footage could be from the Second World War, or any other war.

HAYes, there is the sense that nothing's really changed. The reference for the installation was The Family of Man (1955), an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was curated by Edward Steichen, who gathered images by hundreds of photographers from around the globe that spoke to the state of the world in the decade after the Second World War. It was one of the first instances of documentary photography being treated as an art form.

SAWas the idea of using imagery already in the public realm something that came out of recent global events, or had you thought about this way of working before this?

HAMaybe it was something that happened during the lockdowns. I wondered what you would photograph during the pandemic, in a world where we couldn't interact or touch. I became more and more interested in images that were already out there. I don't know how many millions or billions of photographs are produced on a daily basis and recorded online, but you do wonder whether the world needs more photographs. Should we instead look at what is being produced and what's already out there?

SAIt seems to me that your recent work is a form of documentary photography, but also the antithesis of documentary. You still document things that have happened to real people, but in a way that plays with the medium and narrative. How has your process and intent changed as you've moved from documentary photography into the visual arts? Do you see any link between your practice as a documentary photographer and as a visual artist?

HAIt may sound quite radical, but I do see this work as documentary in nature. The subjects I work with are purely documentary subjects. My intention from the beginning has been to bring my documentary practice into the world of visual art, and to challenge our understanding of documentary. Somehow, at some point, we started believing that the documentary practice can provide evidence of truth. But the meaning of documentary includes ideas of 'traces' or 'evidence' as particles of a much broader reality.

The documentary genre has been used by systems of power to manipulate reality towards a desired direction or belief. As an individual and as an Iranian woman, a lot of the struggles I had when I migrated to Australia were struggles with the image—images that come out of my country or are shared with the world.

I have to constantly fight against those images and justify my being against the images that exist in the mind of society. I would argue that documentary photography also involves artistic intervention, and at its best, can give us a fraction of a much bigger reality.

SAI'm interested in your portrayal of whistleblowers in Agonistes, which documents the stories of government employees at Australian detention facilities. You transform these individuals into three-dimensional historical busts. Is your inference that ordinary people can be heroic? What is it about the role of the whistleblower that interests you?

HAAgoniste is an Ancient Greek word; the root of the word is 'agony' and it refers to someone who struggles internally. The idea for this project came when I visited the Vatican Museum for the first time. There was a section with pieces of different statues that had been destroyed, and an arm and a leg on sticks. It looked quite horrific and that stayed with me. There's so much violence in the narrative around being a whistleblower and the body that is carrying that—I wanted to bring that in directly into this project.

Agonistes came after making Remain on Manus Island. For two or three years after I returned from Manus Island, I hated my freedom. I felt the responsibility I carried in my body. I talked about what was happening on Manus on any platform that I could access.

When I started making Agonistes, I was thinking about the body as a form that carries other people's trauma. What happens to a body that becomes a museum—an archive—of other people's traumas, and preserves these traumas in some way? I also wanted to talk about the body of society as a whole.

The museum aesthetic shown in the marble-like busts of the whistleblowers was not only referring to the idea of the body as a museum for trauma, but also to earlier formations of democracy. It was during the Hellenistic period that sculptors turned their attention to ordinary people for the first time, and showed their emotions and imperfections.

This was also the period where tragedy in theatre became popular. Often in tragedies, the main figure is a person who is caught between the law and the public. They witness something and suffer because of it. They want to tell the public what's happening, knowing they will risk their life in doing so. When they do share it, the public chooses to remain blind to it. That's the nature of tragedy—the individual sacrifices their life and being for the sake of society. For me, the whistleblower is modern society's tragic figure, and so I wanted to link the portraits aesthetically to that period.

SAYou have previously said that art showed you a way of understanding your body in the world. Is this about the role of the individual as a member of society? Or is it about the body as a political entity?

HAI think it's both. I see art-making as a process of 'unselfing'—you can be outside of your body, less focused on what's inside, and see yourself in relation to the broader world. Art-making gives me purpose and meaning. When I couldn't connect with the world during the lockdowns, I felt trapped inside my body. I was obsessively thinking about what was happening to me, and I hated that.

The body is also a political entity, and I think art-making in all forms is political. It's meaning-making. Everything we add to this visual world of art and images adds to future generations' understanding of the world we inhabit today. —[O]