Juliet Bingham on Yoko Ono’s Lifetime of Imagining

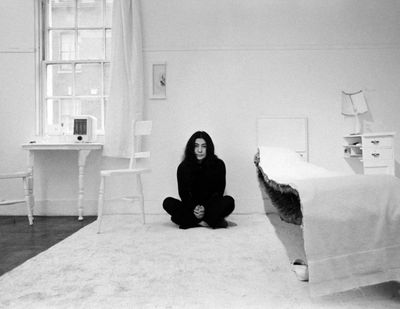

Yoko Ono with Half-A-Room. Exhibition view: Half-A-Wind Show, Lisson Gallery, London (1967). Photo: © Clay Perry.

Yoko Ono with Half-A-Room. Exhibition view: Half-A-Wind Show, Lisson Gallery, London (1967). Photo: © Clay Perry.

Yoko Ono is a collaborator. Whether it be with her audience, or the artists, musicians, and characters that have enriched her seven-decade career, it is Ono's collaborations that tell the story of her life.

The 1960s were a fruitful decade for Ono. She is associated with the formation of Fluxus, the international network of artists and composers founded by George Maciunas, later participating in Fluxus events. Her admiration for the ideas of American composer John Cage, along with her desire to provide a forum for artists and performers, led her to rent a Manhattan loft. The loft hosted the famous 'Chambers Street Loft Series' of performances and events, which counted Marcel Duchamp and Peggy Guggenheim among its attendees.

A trip to London in 1966 to take part in the 'Destruction in Art Symposium' prompted Ono's first solo exhibition in the capital, and a serendipitous meeting that would turn out to be one of the most formidable collaborations of the 21st century.

Now, the 91-year-old artist and activist presents her largest exhibition ever staged in the U.K., at London's Tate Modern. Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind (15 February–1 September 2024) brings together over 200 works from an overflowing archive of her scores, installations, films, music, and photography.

Unpublished photographs of Ono's early concerts hosted in her Chambers Street loft sit alongside footage of the infamous Cut Piece, the performance in which Ono invited the audience to snip pieces off her clothing.

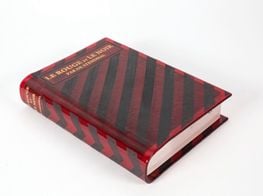

For the Tate show's curator Juliet Bingham, the foundation of Ono's practice—her musical training and her early instruction pieces logged in her self-published book Grapefruit (1964)—placed her at the forefront of avantgarde circles long before the Lennon media frenzy that ensued.

In the following conversation, Bingham discusses the participatory works to get involved in, the string of close-up bottoms that finally get their moment, and what she sees as Ono's enduring message to the world.

ADMany have heard of Yoko Ono in relation to the Beatles and her advances in music, but perhaps some are less familiar with her artistic practice. How would you introduce this show to a friend?

JBA good place to start would be the title, Music of the Mind, which we took as a metaphor for the way Ono sees her work as a way to stimulate and unlock the mind and imagination.

When she was young, she was very sensitive to sound. She used to hide at her parents' house and cover her ears with sanitary pads wrapped with gauze, and light matches as an almost ritualistic way to calm down, block out sounds, and come to terms with herself.

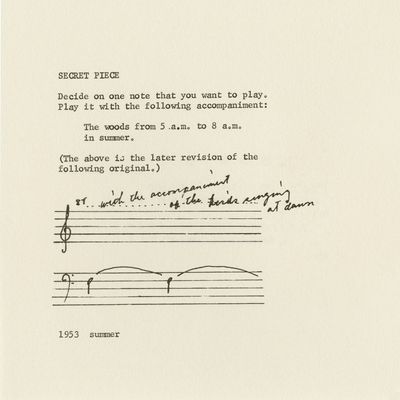

Through both imagination and participation, Ono encourages people to tap into their interior world. Ono's written scores, or 'instructions', are concise, funny, humorous, and at times dark. These act as a way into many of the questions that she was asking: What is art? What is an artwork? How do you, as a viewer, engage with the work? Her instructions are like DIY scores, so that anybody can realise and 'complete' her artworks. As such, they are the backbone of the exhibition.

ADHow were these instructions realised?

JBAt Ono's first ever exhibition at the AG Gallery in New York in 1961, she communicated most of her instructions to visitors by word of mouth, presenting the related canvases and inviting the viewer to complete the paintings. Less than a year later, at her solo show at Sogetsu Art Center in Tokyo, Ono exhibited more than 30 instructions for paintings—her ideas presented as words, only without accompanying canvases. She asked her husband at the time, the composer and musician Toshi Ichiyanagi, to transcribe her instructions in his very careful script because she didn't want them to have the emotion of her own handwriting. This was very radical because she was pushing towards a total conceptual practice.

The typescripts of these instructions were later compiled in Ono's self-published book, Grapefruit (1964)—extracts of which can be found throughout the exhibition, both in large, graphic formats across walls, and as framed original transcripts.

ADWhat participatory elements are presented in the Tate show?

JBEvery room has instructions and almost every room has something participatory.

The sky became a metaphor for escapism and limitless freedom for young Ono. She was evacuated to the countryside during the bombing of Tokyo during World War II. She remembered how she and her younger brother would look up at the sky and imagine menus using their powers of visualisation, as food supplies were scarce. Ono described this as 'maybe my first piece of art'.

Cut Piece has been read in many different ways, as an act of giving and taking, and as a feminist action against violence, but for me, the participatory element is important. It subverts the relationship between viewer and participant, and artist and audience.

Participatory works realise these imaginings, such as Helmets (Pieces of Sky) (2001), where German WWII helmets are suspended upside-down from the ceiling at different heights, and act as receptacles for puzzle pieces that form an image of the blue sky, in reference to the violent fragmenting of hope though war. Visitors are invited to take a piece of the sky as a keepsake. The idea for the puzzle is that you put it back together, as a gentle way of healing and collective participation.

Another work, My Mommy Is Beautiful (2004/2024), in the last room of the show, invites visitors to bring a photograph, or write a message on the 20-metre-wall about their mothers. We're hoping it will develop into an intimate homage to mothers.

ADThe show also features one of Ono's most well-known performances, Cut Piece (1964). Could you explain the work?

JBOno debuted Cut Piece during the Contemporary American Avant-Garde Music Concert at the Yamaichi Concert Hall in Kyoto in 1964, and in her farewell concert, entitled Strip Tease Show, at Sogetsu Art Center that same year. A year later, she performed it at the Carnegie Hall in New York, followed by performances in London as part of the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS).

Tate's exhibition includes photographs of the performances in Tokyo and London, and a film documenting the performance in New York. Ono is on stage in black clothing, kneeling in a very passive way. She invites the audience to come up and cut her clothes with a pair of scissors and take a piece as a keepsake.

Ono spoke about the importance of wearing her best outfits for these performances. When she performed Cut Piece in London, she wore a dress sourced from the Biba boutique by the sculptor Barry Flanagan. We actually have a fragment of the Biba dress in the Tate Archive, which is currently on view as part of an archival display at Tate Britain. Ono was staying with artists John Latham and Barbara Steveni at the time. Steveni took part in her performance, Shadow Piece, as part of DIAS, and Latham later participated in her film Bottoms.

Cut Piece has been read in many different ways, as an act of giving and taking, and as a feminist action against violence, but for me, the participatory element is important. It subverts the relationship between viewer and participant, and artist and audience.

ADIs there a lesser-known work that you felt was important to include in this show?

JBWe've included the previously banned film, Film No. 4 (Bottoms) (1966). Over an hour long, it features close-up shots of bottoms that flash across the screen. Ono referred to the subjects as the 'saints of our time'. The footage was filmed in a West London home belonging to the art dealer Victor Musgrave, and is accompanied by a score written by Ono which begins with the instruction: 'String bottoms together in place of signatures for a petition for peace'. The soundtrack features interviews with participants who talk about the work, why they decided to take part, and what it means to them.

Ono's second husband Anthony Cox—whom she met in Japan in the early 1960s—helped promote her works when she first came to London, and was involved in the filming of Bottoms. You can hear the two of them talking in the background, interspersed with news interviews that Ono was giving at the time.

The British Board of Film Classification (then called the British Board of Film Censors) banned the work after it was shown at a private viewing, which prompted the Royal Albert Hall to cancel their screening of it in 1967, deeming it 'not suitable for public exhibition'. We've included photos of Ono outside the BBFC's offices, where she protested with daffodils, arguing for the film's contribution towards her peace campaign.

ADShould we expect a participatory element to Bottoms?

JBNot quite, but the film script for Bottoms referenced Ono's hope to make a film of smiles, to humanise victims of violence. She wrote: 'My ultimate goal in filmmaking is to make a film which includes a smiling face snap of every single human ... This way, if [President Lyndon B.] Johnson wants to see what sort of people he killed in Vietnam that day, he only has to turn the channel. Before this you were just part of a figure in the newspapers, but after this you become a smiling face.'

It's quite prescient as, of course, she didn't have access to social media back then, and so she was trying to work out a way that you could capture everybody's smile. For the Tate show, we're including A Box of Smile (1967), a small, plastic box with a mirror inside that visitors are invited to look into, and smile back at their reflection.

ADWas there much precedent for performance art amongst women artists in Japan at that time?

JBWhen Ono was in Japan in the early 1960s, she participated in the Japanese performative art collective Hi-Red Center's events, and took part in urban performances alongside the art collective Zero Dimension. These were documented in Nagano Chiaki's film, Some Young People, broadcast on Nippon Television in 1964. However, it was mostly men in these circles. In parallel to Ono's practice, Carolee Schneemann was developing her performance practice in New York.

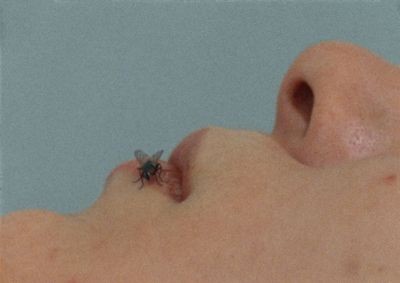

Ono was also in contact with Mieko Shiomi, co-founder of the Japanese experimental music collective, Group Ongaku. Tate's exhibition includes Shiomi's Fluxfilm, Disappearing Music for Face, which was filmed in New York in 1966 and features a close-up of Ono's mouth.

In 1966, Ono was invited to London to take part in the Destruction in Art Symposium, a month-long series of concerts, talks, events, and performances, held mostly at the Africa Centre, and in a few other London venues. Ono was the only woman to have her performances staged as part of the event, and her participation took quite a different approach to the male artists involved, whose work was destructive in a very different way.

ADHow was she received in London?

JBVery well. She had intended only to briefly stay in London for the symposium, but became embedded in the countercultural scene. This led to exhibition offers, the first of which was Unfinished Painting & Objects (1966) at John Dunbar's Indica Gallery, where she first met John Lennon.

He had come by before the opening and was intrigued by Painting to Hammer a Nail (1961), an instruction painting featuring a white painted rectangular panel with a hammer attached by a chain. Visitors were invited to hammer a nail into the panel until the surface was covered with nails.

All of Ono's work is a form of wishing and this idea is very much seeded throughout the exhibition. She famously said: 'A dream you dream alone is only a dream. A dream you dream together is reality.'

On learning that it cost five shillings to hammer a nail, Lennon asked whether he could hammer an imaginary nail. Ono felt she'd met a guy who finally thought in the same way that she did. So there are nice anecdotes like this about when they first met, and we're including a version of this work in the show.

We've also included a number of their collaborations, such as Acorn Event (1968), where they planted two acorns—one facing east and the other west to symbolise unity across the world. They also posted acorns to 96 world leaders, asking each to plant their own acorn for peace.

In 1969, the pair launched their major WAR IS OVER! IF YOU WANT IT billboard and poster campaign using mass media to quickly spread and amplify their message for peace. We'll also be screening a film of their Bed-in for Peace (1969).

ADWas there anything you learned about Ono or her practice that surprised you?

JBWe had the pleasure of visiting Ono's New York studio, where her team pulled out archival photographs, Ono's early drafts for Grapefruit, and rarely seen sculptures that were incredible to see in person. There were fascinating photographs, taken by the Japanese sculptor Minoru Niizuma, of her early concert events that she ran from her Chambers Street loft in New York in the early 1960s.

She must have only been in her late twenties when she took on the lease and basically opened it up—co-running it with the composer La Monte Young—as one of the few progressive performance spaces for musicians, artists, and choreographers. Artists Marcel Duchamp, Isamu Noguchi, and Robert Rauschenberg, choreographer Simone Forti, collector Peggy Guggenheim, and composers John Cage, Richard Maxfield, and David Tudor were among those who attended and participated.

It was here that some of her earliest instructions emerged, as part of a series of concerts and events. She recalls Isamu Noguchi stepping on her conceptual painting, Painting to Be Stepped On (1960/61), with his 'elegant' Zohri slippers.

ADAdvocacy for peace, and the feeling of hope, has been a guiding force throughout Ono's career. If this show was to be seen as her enduring message to the world, what do you see that to be?

JBThe last work in the exhibition is called WHISPER, a recording of her 2013 performance at the Sydney Opera House when she was in her 80th year. In the performance, you hear vocalising and improvising; her words reverberate and echo. Throughout, she repeats the phrase: 'I wish, I wish, I wish . . . let me wish.'

All of Ono's work is a form of wishing and this idea is very much seeded throughout the exhibition. She famously said: 'A dream you dream alone is only a dream. A dream you dream together is reality.'

Seeding an idea and collectively wishing for a better reality underpins all of Ono's works. For Ono, this is a process of transformation and communication that involves looking inside yourself, unlocking your mind, and using your imagination. Her collective call to action is a provocation to change the word, one wish at a time. —[O]