June Clark: How to Come to Terms with the World

In collaboration with The Power Plant, Toronto

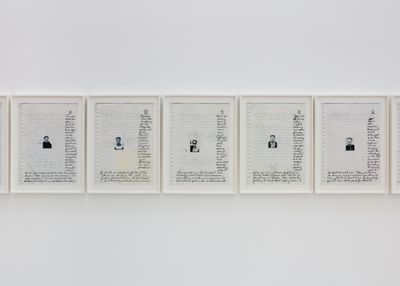

June Clark. Courtesy the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: Dean Tomlinson.

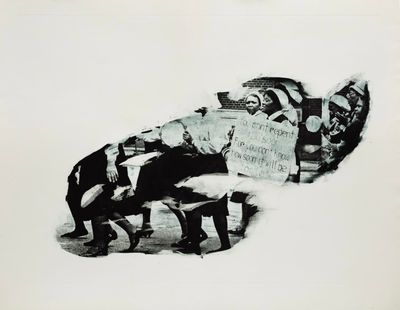

June Clark. Courtesy the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: Dean Tomlinson.

On the occasion of her first institutional survey in Canada, Witness, Harlem-born artist June Clark reflects on the dramatic events that led to her sudden move to Toronto in the late 1960s and her career as it evolved in the wake of that tumultuous period.

In 1968, in the era of the Vietnam War, Clark fled to Toronto with her husband to avoid his conscription, leaving her childhood home of Harlem, New York, and her close-knit family.

Gifted a camera by her husband, Clark began to explore her new surroundings by photographing life on the streets of Toronto. Of the time, she said, 'Of course, I could not re-create Harlem, but I found a bond of humanity that one can usually find anywhere one goes if the eyes are open'1. Eventually, her pastime evolved into an artistic practice that led her to co-found the Women's Photography Co-operative during the 1970s.

In a period when women had little recourse to training or equipment, the collective empowered Clark and fellow women artists to teach themselves and to support one another. Prohibited from using the University of Toronto darkroom, the group used two darkrooms in the basement of Baldwin Street Gallery—opened in 1969 by Laura Jones and John F. Phillips—while Clark turned a closet in her house into a third.

In 1972, the gallery also hosted the Co-operative's exhibition, Photographs of Women by Women—a seminal moment for Clark, who co-curated the show with other members of the group, including Jones, Pamela Harris, Judy Holman, Liz Mancell, Lynn Murray, Linda Rosenberg, and Lisa Steele. The exhibition toured widely across Canada, cementing the group's capacity to create and show its own work.

In this interview, which occurred in the lead-up to her survey June Clark: Witness (3 May–11 August 2024) at The Power Plant in Toronto, Clark discusses the impact of this history on her practice. Clark is incredibly warm and energetic in person. Speaking with her is an invitation to engage with a deeply contemplative and alert mind, always receptive to a good story and appreciative of a hearty laugh.

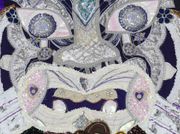

Presenting four distinct bodies of work, the exhibition at The Power Plant offers a highly personal exploration of the intersections between family, Blackness, history, recollection, and identity—individual and collective. Family Secrets (1992) and Harlem Quilt (1997) draw from the artist's memories of growing up in Harlem, inviting viewers to consider the complexities of family bonds and personal histories. The earlier work comprises black boxes, each containing a selection of memorabilia—dairies, dried flowers, keys, and the American flag, while Harlem Quilt, completed following a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, comprises bundles of fabric onto which the artist transferred photographs she shot in the borough's streets, illuminated by strings of lightbulbs.

Another work included in the show, 42 Thursdays in Paris (2004), is a photo and text diary capturing Clark's experiences at a friend's apartment in the French capital, where she regularly took self-portraits in a photo booth, while her most recent work, 'Perseverance Suite' (2021)—a series of sculptures fashioned from metal tools such as rolling pins, shovels, and pitchforks—contemplates themes of domesticity, labour, and resilience relevant to her parents.

The exhibition, which runs concurrently with the artist's solo show, Unrequited Love, at the Art Gallery of Ontario (20 January 2024–5 January 2025), is not only an opportunity to consider Clark's output but also to reflect on her broader contribution to the arts in Canada. Besides regularly showing her work over the past five decades, Clark has contributed extensively to the arts more broadly too: she taught fine art at several institutions, including York University and the University of Guelph; served on various boards, including the Toronto Arts Council; been a jury member for organisations such as the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Association of Art Galleries, and since 2000 has worked as a Cultural Affairs Officer for the City of Toronto government.

The following Ocula Conversation is introduced and edited by Neil Price from an interview he conducted for The Power Plant's podcast, In/Tension, in February 2024. It has been edited for length and clarity and is republished here in collaboration with The Power Plant and with the artist's permission.

NPI'm curious about your earliest influences in art. You have often said that you were gifted a camera when you arrived in the U.S. and started taking pictures, but how did you come to art before that?

JCI came to Canada one day and got a job the next day in administration at the University of Toronto. It wasn't until I was gifted the camera that I began walking around the city. I didn't realise I was looking for the familiar. I had to leave the [United] States with my husband very, very quickly, in 48 hours, with the military police on our trail.

NPBut before coming to Canada, you did not conceive of yourself as an artist?

JCNo. I was an assistant to the chair of speech pathology at the University of Toronto, and I began making photographs. All you need is to encourage someone, and people continually told me they liked my photographs.

Then, I met [Canadian journalist and commentator] Larry Zolf and Patsy Zolf. Patsy said, 'There's a gallery on Baldwin Street you should go and see; they might like to show your work.' That's when I met Laura Jones and John Phillips. They ran the Baldwin Street Gallery, and they had two darkrooms in the basement. It was amorphous; it was very organic that we began.

NPDid you come to a point though, whether in a year or two years, where you said to yourself, this is viable, I can be a working artist?

JCNo [laughs]. It didn't work that way. I just continued to make photographs. It took me a very long time, a few years before I would say I'm a photographer. To make that declaration is a big step, especially if you haven't been trained if you've trained yourself. And that's exactly what we did—we taught ourselves. So, in my mind, I was a part of a group of women, and we just supported ourselves.

NPYou have discussed your artistic practice as meditative, and you have said that the materials you work with guide you—that they present to you how they want to be used. Tell me about that process.

JCWith my collages and my sculpture, the idea comes first. And then I find the material. I decide what I want and need to say, and then I find the materials to say that. Often, I'll go into the studio, and the material will say, 'Well, no'. Often, it will be three or four days, and I might be in the middle of something, and if I am still struggling, I will say, how did you, and why did you start this?

For the last piece I did, Tubman (2023), I tied yarn to chains and then hung them. That was meditative because I was making knots in all the chain loops. I suppose that is my form of meditation, in terms of just doing the same thing repeatedly, and then, suddenly, I have a curtain of yarn.

NPWe see that in your flag works as well, right? Take, for example, 'Moral Disengagement' (2014–2017), which consists of flags whose threads have been pulled away, hanging like tatty strips of fabric.

JCYes, Moral Disengagement was the piece that made me realise I'd been doing flags for about a decade, and I hadn't thought of it. It's just pulling those threads and trying to come to terms with what was happening to this country that I was born in.

NPYou've had a long career in teaching. What excites you when you look at the work of younger artists today, particularly Black artists?

JCWe were discussing Amartey Golding. I mean, that work is sensational. I'm getting goosebumps just thinking about it. You walk into a room and see what he's trying to do—not trying—he's doing it – using materials to say what he needs to say, and you feel it in your marrow. It's so exciting.

Probably I think more about the writers—Dionne Brand, Christina Sharpe. Those people are turning around, influencing, and spurring me on. I'm reading what they have to say and how they are saying the same things we were saying in the sixties and seventies, but [with] a much sharper, clearer sense of where they are in the world. Whereas we were trying to figure it out. They know where they are, and they're trying to guide us now.

NPI want to discuss your Harlem Quilt installation, which was first shown at the Studio Museum in 1997 which you made because you were there for a residency.

JCYes. My mother and sister were still in Harlem, so I had family there, and I would go back and forth, but it was interesting in 1997 to return to Harlem and live there again. I had myriad emotions being on 125th Street because not that far away was 118th Street, where I grew up. My church was around the corner from the Studio Museum, too.

I decided I needed to understand how I was feeling. I had my camera, and I decided if I put it to my eye, I would edit and choose what I photographed. So instead, I decided to set my camera—I had a Leica—in the morning and then hold it at my hip and click as I walked the streets. I never knew until I processed the film each day what I had. I didn't want to edit or editorialise what I was seeing. It was only, I think, this year that I realised that I had the camera at the height of a 7-year-old. And that was very important to me, to do that.

NPThe work comprises the images you took on these walks, transposed into fabrics.

JCThere are hundreds of images because I kept clicking all day. And this isn't digital; it's strictly analogue. There was a Goodwill store on 125th Street, a block away from the Studio Museum, and I went and bought pounds of clothing. I decided to put the images on the clothing to deal with where I was.

I remember I was in the studio, and then I thought, ' I'm cutting up perfectly good clothing that people can use. ' And the curator was so wonderful. She said to me, 'But June, you paid for the clothes, you've contributed that way, it's okay that you are doing it in this way.'

NPThe immersive experience of the installation, enhanced by the lighting, is quite extraordinary. You have created a meditative space where images you captured on your return to Harlem are stitched into pieces of clothing. Are those Christmas lights?

JCNo, I went down to Delancey [Street] and had them made them up. You can get anything on Delancey. I worked with an electrician and had them string the lights. The technology is so different now—now you can do it yourself.

NPWhat is it like to see the work in different iterations and spaces 30 years after you made it?

JCIt's very exciting. I remember the guy I knew on Delancey, and I remember the people who helped me process the work and its making. For me, it was a very important document of that time because, as I say, I got there and realised nothing had changed in Harlem, and absolutely everything had changed.

NPI want to discuss memory because it seems so central to your work.

JCWell, again, that is how I hold on to where I grew up and all those people who influenced me. I did not know how to manifest that in my work other than in Family Secrets (1992) and those boxes; I just made things up.

NPIn Whispering City (1994), a body of large haunting photo-etchings based on your childhood memories, you focus on how images and memory respond to each other. In this series, images you took many years earlier are paired with texts you write today.

JCI started the 'Whispering City' series after having a conversation with my sister, who was my closest friend and relative. She was 18 months younger than me. I remember that growing up, she could finish my sentences. I knew she could sit across the room, and I would know what she was thinking. That is how close we were.

I recalled an incident we were both privy to, and I was appalled that she remembered it differently. I was almost angry. That was when that work came about. The images of 'Whispering City' are 30 years from the 'Whispering City' text. And it was almost as if I realised why I had made those photographs 30 years prior.

NPThey almost became, I don't want to say, a prophecy, but it was almost like they were brought into existence for a reason.

JCThat's exactly right. And in so many of those texts, I heard what my grandmother used to say, or my great-grandmother, et cetera, used to say.

NPAnd some things people said to you as a child were quite harsh.

JCLearning printmaking allowed me to wipe the plate, so you'd get an image, but not the full one. Memory emerges, and it recedes. That is what I was trying to illustrate with 'Whispering City'.

NPSpeaking of memory, let's return to your involvement with the Women's Photography Collective in the 1970s. I know you've mentioned that at that time, it was hard, impossible even, for women to get access to darkrooms.

JCIt was impossible. I always say, what did they think we would be doing in there, in the darkrooms at the University of Toronto, when there were no women allowed?

NPAnd this is the seventies—we're not talking twenties or thirties. My goodness.

JCExactly [laughs]. But in fact, they did us a favour because we taught ourselves. And that's always, for me, the best way. You make your mistakes; you learn. And we sought the photographers that we wanted to emulate.

NPWhat's changed for women and men practising photography as artists, and what hasn't? When revisiting Harlem, you mentioned that you had a similar take, where it changed and didn't change. I'm wondering about working as a woman and as an artist in photography.

JCI suppose it's very different. I don't want to sound like an old fuddy-duddy, but I know that people always say they have no idea how easy it is for them now. But in fact, that is true, that it's inconceivable that you would have people say, 'No, you can't do it because you're a woman'. It almost doesn't even make sense. But I think now, well, we can see it. Women are everywhere and doing everything, and that is incredible, considering what we had to go through.

NPDo you ever enter circles where you feel as though you're being judged as a Black artist or as a Black woman artist practising photography?

JCAll the time. That hasn't changed. I don't feel that they're asking me to tie my hand behind ... I think that when you walk in, there is an assumption, and you say, all right, if you want to feel that way, fine. Or you can try to prove that you don't have to think that way about me.

NPWhat do you remember most about the collective days? Was it just trying to learn and figure things out? We talked earlier about how you would often show each other's work or find places. When you think back to that time, what lingers for you?

JCWhat lingers is that most of us were American, and we were all here for the same reasons. You just did what you needed to do, and you did not think about it. So long as you were not knocking on the door and asking to be let in. Laura Jones and John Phillips had two darkrooms in the basement, and you never thought about not working. There was always someone within the co-op you could call and talk to and say, this is what I'm thinking; what do you think? We just did it.

NPYou have been working in sculpture more recently. In 'Perseverance Suite' (2023), you use found tools and implements...

JCAnd things I have collected and saved. For the 'Perseverance Suite', most of the work has something domestic—I'm using all my grandmother's plates, or cups, or whatever, fabric, coupled with field tools. It's important to me because I grew up with my mother and father working. They had to work together to make a living. That's what 'Perseverance Suite' is all about—domestic and outside work.

NPAre you enjoying this move to sculpture?

JCYes, I am. I'm learning about metal and how to deal with it. There is a woman in Kitchener, Ontario, who's a blacksmith. She's amazing and has also helped me realise what I'd like to do with metal.

NPOn the podcast, we like to ask guests to pose questions for future guests. We had an artist pose this question, and I'd like to ask it of you: How is your artistic practice a spiritual practice as well? I think you've touched on it a little bit.

JCMy whole practice is spiritual. As I say it, it sounds crazy, but all those people who came before me, my parents, my aunts and uncles, the people who lived in the building I grew up in, they're all here. They're all pushing me and saying, yes, you can do this. And we feel very good about what you're doing. It's very, very spiritual for me. I call on them often.

NPThank you. I wonder if you have a question that you can ask of a future artist. It can be about anything. It's not necessarily about artistic practice.

JCI suppose when I ask that, I'm asking that of myself as well: How do we illustrate, how do we come to terms with the world we live in now, and how do we push people forward to be true to themselves? That's what I would say. —[O]