Patty Chang: From Xinjiang to the Atlantic Ocean

Patty Chang. Courtesy the artist.

Patty Chang. Courtesy the artist.

Since the 1990s, Patty Chang, an artist and educator based in Los Angeles, has drawn on the parallels between her body's internal workings and the environmental landscape through writing, sculpture, video, installations, and performance art. In Chang's early performances, her body takes central position as both object and subject—a continuation of performance practices that were initiated in the 1960s and 70s by artists such as Marina Abramović, Hannah Wilke, VALIE EXPORT, and Eleanor Antin, who began using their bodies as sites for examining the (largely male) constructed notions of female identity that colluded with objectifying women. Chang's practice, however, moves beyond simply subverting the male gaze, using her body as a lens to explore the myriad of ways landscapes can produce, consume, expel, and express vulnerability and unpredictability.

Born in 1972 in San Leandro to Chinese parents, Chang received her Bachelor of Arts from the University of California, San Diego, where she studied live art and performance-based practices under Eleanor Antin. Chang was drawn to the discipline's ethos of immediacy and use of the body as a lens through which to explore and address wider feminist, representational, and more recently, environmental concerns. This quest also allowed her to challenge 'social constructions and cultural imaginings of Asian and Asian American women and culture',[1] thus appending her body with an anti-racist agenda. As theatre scholar Erin Striff argues, women artists use body-based art as a site for 'the disruption of cultural associations'.[2]

Among Chang's early works is Shaved (At a Loss) (1998), a video—just over five minutes long—that documents the artist performing the intimate act of shaving her pubic hair blindfolded. Straddling voyeurism and discomfort, Chang, elegantly dressed in a white corset and purple silk skirt, speedily carries out the action. By introducing the possibility of harm in a potentially dangerous situation, Chang 'exposes her genitalia in a way that does not merely reinscribe sexism or racism, but actually resists dominant, white, masculinist objectification of Asian women'[3], explains educator Leta Ming. In another early video, Fountain (1999), the artist crouches on the floor and faces her reflected image in a large mirror filled with water, which she proceeds to sip in a conceptual attempt to unify the self. Fountain draws on the Greek mythological figure Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water, eventually dying at the site of his self-absorption.

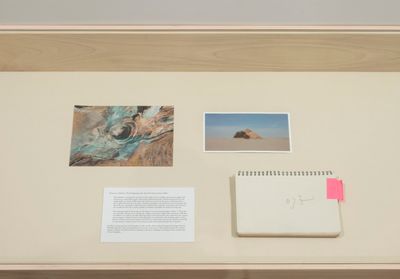

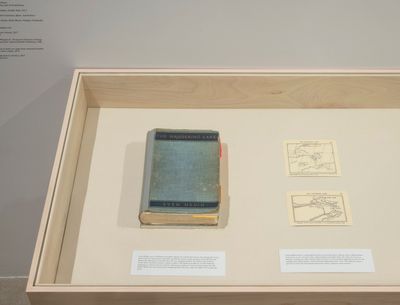

Water continues as a theme in Chang's solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Patty Chang: The Wandering Lake, 2009–2017 (17 March–4 August 2019). The exhibition, which premiered at the Queens Museum in New York between 17 September 2017 and 18 February 2018, features the artist's eight-year project departing from the 1938 book by Swedish colonial explorer Sven Hedin, which documents his search for a mysterious transient body of water in Lop Nur, Xinjiang province, China. Amidst political and logistical challenges, Chang made a series of visits to Xinjiang in an attempt to reach the now evaporated lakebed, which dried up after irrigation works and reservoirs were developed on the Tarim Basin, enabling its use as a nuclear weapons testing site between 1964 and 1996. The journey resulted in the film Minor (2010), which was shot a few months after clashes between Han Chinese and Uyghur minorities in Urumqi in July 2009—the work documents different actions tied together by the themes of communication, movement, collective and individual bodies, and the landscape.

Feeding into the installations, performances, sculptures, collected ephemera, and writings—an artist book was conceived as a central part of this project—that are part of this exhibition, is a meditation on water as both physical and metaphoric influence, intertwined with the artist's personal experiences of mourning, pregnancy, geopolitics, and landscape. Powerful works include Invocation for a Wandering Lake, Part I (2015), which is projected onto cardboard panels at the entrance of the show and captures Chang washing the carcass of a sperm whale on a shore in Newfoundland, Canada, accompanied by the sound of gentle waves.

In this conversation, Chang charts her trajectory as an artist, from the body-politics that defined her early works, to The Wandering Lake, in which the body is used as a lens through which to explore contemporary society.

JDHow did you come to performance, and what do you make of the developments that have occurred within the genre? Performance art of the mid-1990s was very different from what it is today.

PCPerformance art is always changing. Perhaps more so in the last ten years, as exposure for the discipline has increased along with public programming at institutions. As someone who performed in the nineties, I have mixed feelings about this, in relation to its histories of transgression and being outside of the market and pushing back against institutional framing. There is, however, a certain power to it being a legitimate art form represented in institutions. I think that has also opened up the discipline to a lot of younger artists. I started performing during my time as a student at UC San Diego in a department that was very much centred on conceptual art and critical thinking. Eleanor Antin was teaching a writing class and I later took a performance class with her. At the time, performance seemed to be the right medium for me to express ideas in an immediate way. To have that live relationship with an audience means that they also feel this immediacy.

I started performing at school and continued to perform live when I moved to New York at a time when I had no money, no technology, no camera, and no computer. At some point during this time, I began working with a friend who made videos commercially, who would film some of my performances, which I showed at Jack Tilton Gallery in New York. I later filmed old performances this way and performed new work directly for the camera. I also worked on longer pieces centred around constructing narratives. So that's how I started working in performance before moving to video and now, with my teaching at USC [Roski School of Art and Design], I highlight the importance of the relationship between video art and performance art, and the changing relationship with technology given that students have much more of a relationship with it than I ever had.

JDYour work makes use of the body to research the conditions of existence, producing meaning by exploring the edge of known or posited limits. Would you say that the body is the ultimate medium for manifesting your ideas? What would it mean to remove your body's visible presence from the narrative of your work?

PCThis is something that I thought about a lot for The Wandering Lake. My use of the body-as-subject was so present in my early performance work, so I began to push against that. Throughout this eight-year project, the body has always been used as a starting point to filter or construct meaning during performance or research.

One example was when I first visited Uzbekistan to research the shrinking of the Aral Sea with a very open-ended approach to see how it would unfold. I found out prior that I was pregnant, and I had just started experiencing morning sickness and became very conscious of my bodily reaction to this new environment. There was a really heightened quality to this experience, which also affected my ability to carry out research and make intellectual decisions about direction and so on. After returning to the U.S., I realised that when I go to research and look for information in different places, it isn't just an intellectual pursuit, it's also my body filtering the information and experience. This lens of morning sickness became a point of departure for when I returned to the Aral Sea to make work and found that there was a lot of resistance to me, being a potential threat as a foreigner.

The act of pumping and discarding my breast milk points to your question about the absence of the body. With the piece Letdown (Milk) (2017) there is no body present—not just the maternal body but also the body of water absent from the Aral Sea. I took these quick images with a point-and-shoot camera as casual documentation of this daily ritual of pumping. It also stands in for not being able to photograph other things because of the political situation, as well as how representation can sometimes fail us.

JDThe installation Letdown (Milk) intervenes in the landscape, suggesting a protest to surveillance and policing in Uzbekistan. Would this be an accurate reading of the work?

PCIt was definitely a reaction to the constraints both on my first and subsequent visit, as people around me—including my translators and drivers—would remind me not to take pictures of certain things. The more I speak about something being political, the easier it is to shut it down, which is why I don't necessarily speak of these interventions as political acts. I am more concerned with how to deal with sensitivities and troubling a situation without having it censored.

JDIn her book Hold It Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art (2013), Jennifer Doyle 'searches for the politics embedded in artworks that relay their message through emotion not as a means of "narcissistic escape, but of social engagement."' Have you encountered any controversy in relation to the emotional bearing of your early works?

PCThe idea of controversy shutting down the reading of a work is not something that I think my work engenders. People have told me that they observe a distancing mechanism in my works even when they are personal, intimate, or working with issues that might be sensitive in some way. In general, I haven't encountered this, but sometimes I do work with subjects that might deal with difficulty.

For example, in the project, The Wandering Lake, one of the first video pieces I made for this project was Minor, which was filmed in Xinjiang when I was looking for Lop Nur—known as the 'Wandering Lake'—at a time right after the 2009 riots in Urumqi. I approached this in a very oblique way so that the work isn't directly about the political situation. I didn't want to get anyone in trouble, so the work doesn't speak directly to that particular event, even though it is situated contextually where these events are unfolding. When there's a fixation on the visible, other things get erased, but when you enter through another lens perhaps this allows things to exist simultaneously in the space.

JDWater as a means to explore ideas that cross geographies and identities is a strong theme throughout your eight-year project The Wandering Lake. Could you discuss the performance actions that you created as part of the project and how they engage with water as a theme?

PCWater is present throughout this project, both metaphorically and physically. The Aral Sea, the South-to-North Water Diversion Project, the Atlantic Ocean near Newfoundland, and Lop Nur are all present as subjects. The phrase 'The Wandering Lake' comes from the eponymous book by colonial explorer Sven Hedin. I was interested in the idea that a body of water could disappear and reappear elsewhere. I was also interested in the psychological reaction to a landscape as something that we believe to be fixed to a certain extent, changing drastically in a very short amount of time, and how that would rearrange our ideas about reality, safety, or ourselves.

In The Wandering Lake, Part 1 (2016), I washed a dead whale along the shores of Fogo Island in Newfoundland. The act was a type of ritual to honour the dead being. In Configurations (2016), I travel along the South-to-North Water Diversion Project in China, which is the longest aqueduct in the world, and urinate every time I come upon it. The action made me think about the cycles of Chinese dynastic history and the link to the flooding of the Yellow River, as well as the huge abstract scale of the construction of the aqueduct in relation to individual people.

It tends to be hard to think of the world changing—we imagine it to be fixed. For instance, in relation to climate change, we can't imagine how the world will look in 20 or 50 years. Movement and the relationship to colonialism come into this. It is believed that the government used Hedin's maps for the highway system through that part of the country. We think so much of human subjectivity, but is there a way to move between the back-and-forth flows of the human body, the environment, geographies, ecosystems, and other subjectivities?

JDHow did you first come across Sven Hedin's book The Wandering Lake (1938)?

PCThe text was really just a springboard for ideas, and it was something I encountered by chance. I was preparing for a show at the Arrow Factory in Beijing—an independent art space in the middle of the city. At that time, I was thinking that I wanted to go to Xinjiang, but I didn't have any concrete ideas of what I wanted to do there. All I knew was that it would have something to do with the desert landscape. I spent time researching the area at the Brooklyn Public Library and Hedin's book came up in the catalogue search, so I started reading it. The image of this migrating body of water really stuck with me, as well as the fact that Hedin was commissioned by the Chinese government to lead an expedition to the lake. These two things resonated and made me want to investigate and try and get to the Wandering Lake.

After working in Xinjiang, I also filmed at the Aral Sea, pumping my breast milk while travelling to the receding water's edge as an act of sympathy with the loss of flow to the Aral Sea due to state-controlled irrigation practices. The Aral Sea, combined with the aqueduct Lop Nur, as well as the washing of the whale in the Atlantic, became the basis of my project The Wandering Lake. These impacted geographical regions are placed in relation to personal events, such as my father dying, and my son being born. I made two videos, one titled Que Sera, Sera (2013), the other Invocations (2013). One video captures my mother reading a list of invocations relating to a medicalised death, and in the other video I'm singing 'Que Sera, Sera' to my father on his death bed while I am carrying my son. In this accumulation of performances, live events, and experiences of the body in the world, I could not help but think about them as interrelated and part of a whole. Though they were undertaken separately, the works built up into a type of ontological view of how we exist as individuals in the world with others and the world itself.

JDDo you envision working on more long-term projects like The Wandering Lake in the future?

PCI had a period when I didn't want to work with the art gallery timeline, but I didn't know that this project would take that long. There was value in letting things unfold this way as opposed to the intensity and time compression of my earlier work. I am not sure if I will work this way again, but I am working on something right now that continues some of my concerns on the body and the environment.

Currently in progress is a project called Milk Debt for 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica. The title Milk Debt comes from the debt in Chinese Buddhism that is attributed to the child for the impossibility of ever repaying the mother for raising and feeding it with her breast milk. Therefore, it is necessary to repay the debt through payments towards the afterlife of the mother in the form of joss paper or payments to the temple. Milk Debt is a work that binds us to our history. The debt is to past generations but to the earth as well. The Milk Debt videos consist of a woman who pumps her breast milk in front of an audience while reciting a list of fears compiled by multiple people living in Hong Kong, Los Angeles, and other geographical regions and communities. In Los Angeles, we filmed in a recording studio and domestic spaces, while in Hong Kong we filmed at a protest against the extradition law.

I believe that the act of lactation is an empathetic act. Biologically, breast milk is created when the body starts to produce the hormones of prolactin and oxytocin. Oxytocin is also a hormone that is produced when someone is in love. The act of producing breast milk allows the woman to engage in this state of being, which some might describe as being more connected, open, and accepting, and not thinking of oneself first.

JDWhile The Wandering Lake isn't necessarily a political project, it does deal with the politics of place in relation to the body and wider environmental issues. Do you see the role of the artist as being the moral conscience of society?

PCWhen you say moral conscience, it makes me think about living above standards, which I feel that I would fail very badly at. I consider myself as someone who is complicated, and my actions reflect that. I do think that artists respond to the world that we are in with all its complexities. I am trying to look at these issues that I experience and make sense of things through the works I make. It's important to have different expressions and visibilities in the world and I am interested in pushing these forward. I have always worked in a space where my response to some of these issues are bodily. That's always been the space I've inhabited with my works.—[O]

—