Theaster Gates

Theaster Gates and Gold Tectonic (2017). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kitmin Lee.

Theaster Gates and Gold Tectonic (2017). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Kitmin Lee.

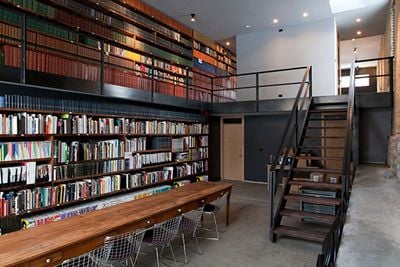

In 2009, Theaster Gates purchased a vacant building on the 6900 block of South Dorchester Avenue, and turned it into a library. As the project developed, it would become known as the Dorchester Projects, with Gates acquiring other buildings to create social spaces centred on culture, such as Black House Cinema, which hosts screenings and discussions of works by and about Black people. He has likened his work with Dorchester Projects to that of being a potter, which relates to the way his practice is ultimately concerned with transformation as a tangible creation of form that directly acts in the real world. In 2011, Gates built on what he had accomplished on Dorchester Avenue by acquiring a shuttered housing development as a joint venture between Rebuild Foundation, which Gates launched in 2010, and Brinshore Development, converting the complex into mixed-income apartments, including an arts centre with a dance studio, public meeting space and a garden, in partnership with the Chicago Housing Authority. (Designed with architectural firm Landon Bone Baker, it opened in 2014.)

In 2013, Gates bought the former Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank from the city of Chicago for one US dollar in exchange for committing to raiseenough money to stabilise the building, which he renovated into the Stony Island Arts Bank through the Rebuild Foundation. The Stony Island Arts Bank was transformed into 'an institution of and for the South Side'—a hybrid gallery, media archive, library and community centre—and was opened in 2015. It is where Rebuild's archives and collection are housed, along with the personal collection and library of the Johnson Publishing Company, publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines, and the vinyl collection of late DJ Frankie Knuckles.

To finance the Arts Bank project, Gates turned his 2013 Art Basel Unlimited project, BNKUDRWTR (for which he presented the Stony Island Bank's sign and teller window and a tarred platform that represented the damage done to the roof of the bank) into an opportunity. At the White Cube booth in the main fair in Basel, he sold 100 marble slabs taken from the walls, counters, and 'shitters' of the bank and inscribed each piece with the phrase 'In Art We Trust' to support the project. Gates found poetry in the gesture. 'The bank should become the currency that the bank uses to pay for itself, and it should be bankers who revive the bank', he said. Of course, by then, Gates had long supported his work from sales of his art in galleries, which often comprised of fragments taken from the buildings he restores. But the artist sees no difference in the way he approaches object- and project-based art. On his practice, he has said 'there is something that's core, like painting, except you don't know what to call it. It has to do with space, and one's ability to manipulate materiality on a very wide level, whether it be clay or an abandoned building.' Gates does not describe his projects as community-based, nor does he see himself as a social activist. 'These are never my labels for myself', he explains. 'What they represent is a deep desire the world has to classify people which ultimately leads to unnecessary fractures in oneself.'

Gates studied urban planning and ceramics at Iowa State University, before getting an MA in fine arts and religious studies from the University of Cape Town, and later returning to Iowa State to pursue a Masters in Sciences in urban planning, ceramics, and religious studies. His first breakthrough project, as he recalls, was Plate Convergence at Hyde Park Art Center in 2007, a dinner party-as-performance that was attended by both the art world and local community, after which he participated in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, and in 2012, he presented 12 Ballads for Huguenot House at dOCUMENTA (13). Between 2008 and 2014, Gates was a lecturer at the University of Chicago, directing the university's Arts and Public Life Initiative, which included the Arts Incubator and Place Lab. During this time, Gates persuaded the university to acquire a two-storey building on East Garfield Boulevard to become galleries and studio spaces for the Arts Incubator, which opened in March 2013. Since 2014, he has been a professor in the university's visual arts department, and in 2015, he presented Three or Four Shades of Blues at the 14th Istanbul Biennial. When he won the Artes Mundi 6 contemporary art award in January 2015 at the National Museum Cardiff, Gates shared the £40,000 prize with the nine other finalists. 'We deserved it together and the brilliance within that cohort helped me understand that', he explains. 'I did not come to that decision alone. I am thankful for other artists.'

SBYou've described yourself as 'a full-time artist, a full-time urban planner, and a full-time preacher with an aspiration of no longer needing any of those titles.' Each role points to your background in urban planning, religious studies, ceramics, and fine arts—combined into what you have described as an expanded practice for which no name yet exists.

How did you decide to pursue these specific subjects?

TGMy disciplinary interests were really borne from what I thought my strengths were. They were not considered based on what the kind of job I thought I could get later, but rather, what seemed to make sense to my interests. It took some years to figure out how these things would work together, but there was no burden to the process. I felt I was really looking for something—like a truth or a way to deepen my own ways. Planning, sculpture and religion were trajectories of the seeking I was doing.

SBFor Plate Convergence, a dinner party-as-performance staged at Hyde Park Art Center in 2007, you created a story about a pottery commune in Mississippi founded in the 1960s by a Japanese ceramicist called Yamaguchi, whom you identified as your mentor. In this story, Yamaguchi came to America after escaping Hiroshima, married a black civil rights activist, and created a ritual centred on 'conversations where people came from all over to discuss issues of race, political difference and inequity.' How did you develop this idea for this performance, and that particular backstory?

TGYamaguchi was a way that I could discuss my real engagement with a traditional craft that was not of my own culture. I wanted a way to both think through ways of convening and offering a grand assembly, but I also wanted to show off my clay chops. Instead of having an exhibition of ceramic wares, I felt clay things needed to be experienced. There were also these conceptual leaps that happened for me with the formation of a character who could act as doppelgänger to my personal interests. Another thing that became apparent was that by shifting from what could seem a Black-White binary to a Black-Asian conversation, race landed as simply another ingredient in the narrative of craft and making. Shifting the binary felt really important and allowing people to view 'works of art' with a context that was not about my hand, but a conceptual 'other', gave me distance from the work and others distance from me. It was a liberating project.

SBYou've said that Plate Convergence was a breakthrough in terms of your 'object-based and engagement-based' interests coming together. At the time, you said: 'I was still trying to figure out what my art was and how to be a good citizen in a place like Chicago.'

Has the performance grown in meaning since you staged it? There is so much resonance with its gesture given what is happening in the United States at present...

TGPlate Convergence demonstrated for me that developing the work is important, but establishing a context and framing mechanism for my work is equally important. I was interested in creating the preconditions that would allow things to happen. I wasn't so interested in dictating the politics of people's engagement as much as I wanted to help make the mix. In many ways, this is why I resist the notion of my engagement with a certain kind of ceremonial or symbolic engagement. I actually don't think I'm interested in that aspect of encounter. I am interested in the architecture of encounter and the set up. Given this political moment, I am not sure if I think my work is more relevant, but it feels like more people around me are interested in some kind of direct 'social-deposit' of their time and talents. What is clear is that rarely do we teach people how to listen to themselves or their callings and direct them instead to a world system that will only know how to exploit the gift. To that end, so much more time should be spent teaching people how to hear themselves and have empathy, so that we might hear and feel each other better.

Labour remains my protest. Art and action, my only weapons.

SBIn 2013, you bought the Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank, which you renovated through your own means, opening the Stony Island Arts Bank in 2015 as a hub of cultural activity. The long-term intention of the work you are doing in the area, Chicago's South Side, is to create multiple hubs that might combine to form, as you called it, a 'miniature Versailles'.

How do you manage such a large-scale endeavour as it expands, and how do you prevent it from falling into the processes of gentrification?

TGThe forces that shape actual gentrification are much more corruptible and invisible than the work I'm doing. Neighbourhoods that are poor and of colour, all over the United States, are at risk of significant change. The Arts Bank is a hope form that allows my belief in the black South Side to be made evident, at a time when no one was willing to consider it a great centre. It wasn't until other kinds of investments and announcements of investment were initiated that the developer market became interested in this sleepy area.

Unfortunately, we only have two words: blight and gentrification. When the city is broke and the neighbourhood defeated, no one wants to be there, and those who live there, perhaps, have to fight to make the place relevant and meaningful and fight for resources; a dark place. But when the resources come, so often they come with no deep consideration for the people who lived in the place. This under-named dialectic between blight and gentrification is something I'm trying to work against. Artists don't gentrify places; we bring life through our energy. Cities, development companies, legislation, real estate agents, and profit-seeking fund managers see a place that has potential and their chief concern is maximizing profits. The period from blight to gentrification encompasses intense urban mechanisms that are too broad, expensive and complex to blame on artists. The arts bring light. The work that has to happen now requires a commitment to equity, opportunity and balance. These values have to be loaded into our fierce commitment to wealth creation.

If I had the burden to sustain everything I have produced, this would be enough to make me not produce anything. The Bank, to those who saw it in the beginning, was not only unsustainable; it was considered an albatross. No one calls the Bank an albatross today although we don't have a 20-year plan for its use. We can see from this political moment that even when people spend 120 years developing a somewhat reasonable political platform with the intention of gross institutionality and sustainability, that one person has the ability to undo the good that others created. In this way, I feel more intensely that to give vision and hope to a place is the beginning of sustainable futures. Buildings, organisations and people rise and fall.

SBYou have said that art is about 'the ability to look at the world and see a moment, see a gap, and do something with it and make something happen.' This relates to your intention to create 'black space', which—as you have explained—is 'about what happens when there is a unity of vision and a singular awareness of a set of things'.

How do you find the will to create platforms that bring people together in order to develop, sustain and nurture a unified vision?

TGIf I focus on art, this is the most important platform of all. The ability to construct a world and share with the world the power of converting potential into action.

SBHow might you relate this kind of social practice to your work in general?

TGThe silos between art and the social is contrived. I believe that people matter and space matters and I'm committed to working as hard as I can on the topics that well up in my belly. The work I do is one work, one impulse, one imperative, one permission, different forms. It is always about affect, intention and aesthetics.

SBOn how the sale of your work is used to finance the projects supported by the Rebuild Foundation, you have challenged the notion that 'purity' is lost when artists become conscious of the art world's economics, or use these economics for their gain, finding power in manipulating the market for the sake of your objectives. You have also talked about using poetry to 'ask the resources in this world to do more'.

What have you learned when it comes to finding ways to use the market to support your work, or asking the world's resources to do more?

TGI don't believe that I'm using the market. I'm making art. I believe in making art. I make art because my life would be horribly boring without it. Purposeless. Art with the biggest 'A' possible. Resources flow through me. They always have and I've never had a problem with the flow even if I had problems with my perception of having more than others. I know that the work of an artist is to be a conduit. I've tried to do that. But making art is not a means to an end. It's really important to highlight this point, because sometimes it seems that this preoccupation with the complexity of resources cheapens and perhaps even deflects my deep value for processes of making.

To this end, whatever I have now or had before has always been used toward my own audacious consumption. It sometimes happens that my audacious consumption has an impact on the people and projects around me.

SBFor your 2015 project at White Cube in Bermondsey, Freedom of Assembly, you 'explored the theme of assembly in its widest sense, enmeshing ideas of an autonomous art object with notions of individual freedom and the empowerment of place.' At the time, you defined your metaphorical understanding of freedom of assembly as being 'the right to form associations independent of the market or other governance'.

What you have learned about the politics of assembling people and managing resources outside of institutional, financial, and/or government frameworks?

TGAssembly requires intentionality, care and humility, most of which I don't have. I have to understand the role I play in large acts of engagement and believe that my investment of time and energy will move some needle forward.

I've learned that I am no expert, but what I'm interested in is creating extended conversations through the work, and if I ask the right questions and make space to really listen to others, great things might happen. I have to lead from my personal desire and allow the forms to follow.—[O]