'A Third Gender' at Japan Society, New York

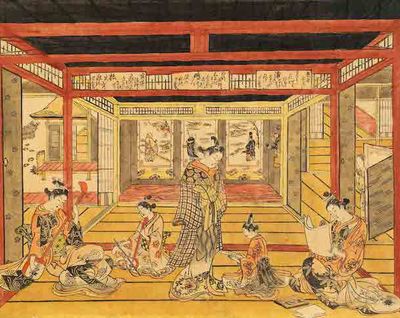

Okumura Masanobu, Perspective Picture: Triptych of 'Three Poems on Autumn Twilight' (ca. 1742–1744). Hand-tinted woodblock print with brass filings. Sir Edmund Walker Collection. Courtesy Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. © ROM.

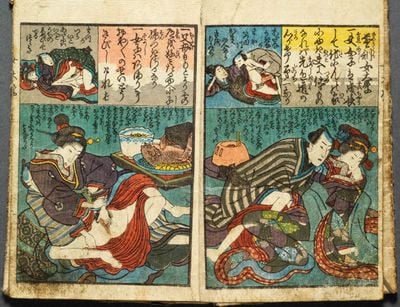

In a beautiful hand-tinted woodblock print less than 12 inches high, we see an 18th-century tea house, rendered in expertly drawn Edo-period perspective, where three elegant prostitutes and their two trainees await their clients. The two women to the left play music, while the two to the right are reading aloud, one from a love letter, the other from a poem-card. In the centre, and clearly the focus of attention, stands the most beautiful of them all. But it might come as a surprise to learn that the central prostitute of Okumura Masanobu's Perspective Picture: Triptych of 'Three Poems on Autumn Twilight' (c 1742-44) is a wakashu: an adolescent boy who was imagined by his contemporaries to be neither a man nor a woman.

The remarkable exhibition A Third Gender—Beautiful Youths in Edo-Period Prints and Paintings at New York's Japan Society seems timely (10 March–11 June 2017). As the most backward and repressive attitudes regarding sexuality are embraced at the highest levels of the United States government—and voiced most specifically by the vice president—this show opens a series of windows on to Edo-period Japan (1603–1868) and a culture where it appears a much greater range and fluidity of gender categories and sexual expression were accepted.

The exhibition was originally organised by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, Canada, and all but five of its 86 exhibited works (more than 60 of which are woodblock prints) come from the ROM's permanent collection. At Japan Society, it has been beautifully installed and occupies the institution's entire exhibition space, which has been divided into a series of interconnecting rooms for the occasion.

The wakashu were the beautiful youths of the exhibition's subtitle. They had reached sexual maturity, but had yet to undergo the coming-of-age head shaving ceremony that marked their entry into adult manhood. (In other words, they were generally between 11 and 18 years old, though some were over 20.) Though they were biologically male, their age and appearance were sufficiently important in the Edo-period comprehension of gender to qualify them as third gender. They were sexually desired by both men and women; participating in romantic and sexual relationships with adult men and both young and adult women.

However, it would be wrong to imagine that sexual relations in Edo-period Japan were enjoyed in a sybaritic free-for-all. Social structures were governed by the strict hierarchical rules of ancient Chinese Confucianism that had been imported into Japan in the 6th century. Men were regarded as superior to women, and older people superior to the young. As far as men were concerned, their position within the hierarchy was governed by profession and was hereditary. Social mobility was almost unknown.

Scholars suggest that sexual roles and activities were governed more by social position than by personal inclination or desire. In fact, ealthy men at the top of the Edo-period hierarchy so dominated sexual mores that Joshua S. Mostow of the University of British Columbia, and co-author of this exhibition's catalogue, describes the society as 'phallocratic'.

Outside of monogamous heterosexual marriage, legal sexual relations took place only in licensed pleasure districts (which is where Masanobu's teahouse would have been located). Women occupied only two sexual categories: they were either non-professional women who became wives and mothers, or they were prostitutes. And a number of the prostitutes portrayed in this exhibition were male, or wakashu.

Thus we come to the images in this exhibition against a highly complex context. Until recently, even experts in the period were confused between representations of wakashu and young women. This exhibition breaks new ground in this regard, particularly in identifying wakashu by the particulars of their hairstyles.

A Third Gender offers up both an exhibition of exceptional moral complexity and an array of beautiful objects rendered with the utmost skill. One of the simplest and most stunning images of a wakashu adorns an 18th century paper scroll, just over two feet tall. Here the youth is portrayed as a seller of fans, and he wears an almost transparent kimono. If this were not enough to suggest his sexual availability, experts assume that the empty space above him was intended for an inscription like those that appear on similar representations and which describe the wakashu as a seller of his body who is 'ready for love'. (The image is both compelling and arguably tragic. It is unclear whether as voyeurs today we are complicit in an exploitative trade, or witness to a sexual freedom societies' norms have rendered elusive.)

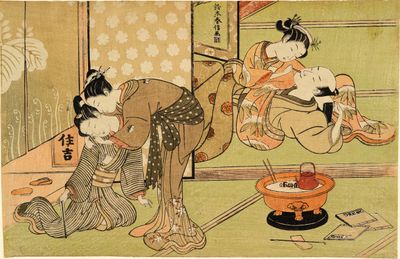

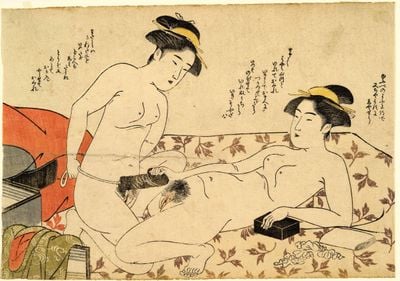

Suzuki Harunobu's woodblock print Two Couples in a Brothel (1769-70) is even more complicated. The couple on the right are an older man and a young prostitute. (In a sign of what appears to be affection, she is plucking the stubble from his face.) To the left, an older woman coaxes a coy wakashu. What is unclear is the relationship between the two men. Is the older man the father of the younger, or does he employ the wakashu as his lover? What is perfectly clear in a number of the highly explicit prints in the exhibition is that their subjects are engaged in sex of one sort or another. We witness a woman masturbating while she observes a couple having sex. In one remarkable print, we see two women coupling with an outsize tie-on dildo. Most often however, men (either adults or wakashu) are depicted penetrating young or mature women.

This is difficult moral and legal territory. First, wakashu were as young as 11 years old, thus making their sexual couplings taboo in contemporary Western society. Second, there is the question of whether representations of these couplings are legal or acceptable to either museum visitors or funders. The Japan Society organisers point out that this exhibition would be difficult to stage in contemporary Japan, or at least in its publically funded museums, and in truth even here they have curated their material judiciously. There are images of homosexual penetration in the exhibition's scholarly catalogue, but none are included in the exhibition.

Still, we should celebrate Japan Society's courage in staging this provocative show, and congratulate their guest curator Asato Ikeda of Fordham University, New York. A great deal more can be derived from A Third Gender by learning from distant Edo-period attitudes than by attempting to impose our own contemporary assumptions upon it. —[O]