On The Player And The Game: The Jeff Koons Retrospective

The Jeff Koons retrospective at The Whitney Museum of American Art is many things to many people. This is especially true of the critics who have weighed in on the show—the largest exhibition of a single artist the museum has ever mounted, and the last exhibition at its current address.

And opinions have been predictably polarized—as Benjamin Sutton’s roundup of critical responses to the show for artnet illustrated. On the one hand, Vulture’s Jerry Saltz was “predictably ecstatic,” and The New York Times’ Roberta Smith offered “a startlingly glowing review.” On the other, vitriol abounded, leveled at Koons’ well-documented commercial lust, including Thomas Miccheli of Hyperallergic’s judgment of Koons’ work as a, “surrender to the leveling forces of consumerism.”

Indeed, as Carolina A. Miranda wrote for the Los Angeles Times, the reviews have been as colourful as the show itself. So she produced the reflection of all reflections: a poem summing up the Koons effect by cutting and pasting together opinions by those including The Guardian’s Jason Farago into incisive, abstract verse with lines like: “He irritates most when he insists he has no desire to irritate.” This sense of irritation always tends to provoke the more apocalyptic critiques: For The Nation, Barry Schwabsky wrote: “Koons turns art’s precious promesse du bonheur into a New Age mantra of blissful idiocy.”

But as ever, it is Koons who has the last laugh. The result of this retrospective is the production of a critical heap that resembles the keynote sculpture of the exhibition itself. Devised in 1994 but only realized now for the Whitney retrospective, Play-Doh (1994-2014) is a sculpture depicting painted lumps of modeling clay cast in aluminum. It was the straw that broke The New Yorker’s esteemed critic Peter Schjeldahl’s back: leading him to muse how this piece “might stand as an imperishable symbol of art’s present worldly estate: child’s play in a game with no-limit stakes.”

Play-Doh is indeed monumental: an assemblage that is both conclusive and fragmented, and as open-ended as Miranda’s lyrical homage to the artist who has become so contentious critics can’t even keep up with the sheer volume of discussion. On one point, for example, Jed Pearl of NYBooks wrote, “Too many column inches have been wasted on his stint in the early 1980s as a commodities broker on Wall Street,” while Ed Gibson of New Criterion posed that in his view, “too little attention has been paid to Koons’s five-year career … on Wall Street.”

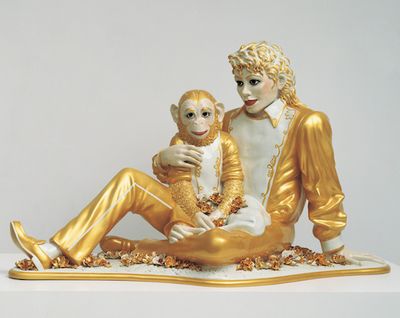

Is this the colour Miranda both observed and reflected in her critical poem? Yes. When it comes to Jeff Koons, everyone has an opinion, and there is a sense that this is exactly what he wants. It's this position that explains how Travis Diehl observed in his review for the LA Review of Books, that this retrospective has become more about Koons himself. An artist whose presence Roberta Smith described at automaton-like, and who Whitney curator Scott Rothkopf has called an artist who has managed to be define the arc of three decades: one that tells the tale of hypercapitalism’s rise, and with it, the hypercapitalists—of which Koons is one.

But, while taking into account Diehl’s point that, “one of the fascinations of the Whitney show has been the near unanimity of the critics of record, who appear to be of the opinion that it’s high time for everybody, like it or not, to make their peace with Koons,” perhaps we need to take this one step further. In thinking about Koons’s work—and the career trajectory of an artist that has been labeled as a business artist, a real artist, and not an artist at all—the fact that the show has become all about Koons points to the reality that this show is not about Koons at all.

Because when it comes to Koons’s automaton persona, we must also consider his automated practice, which recalls what Debord wrote of automation, which “confronts the world of commodity with a contradiction that it must somehow resolve.”

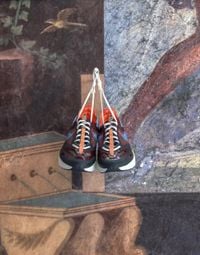

We all know that Jeff Koons is an industry. From his breakthrough 1980s series, The New, which encased various models of vacuum cleaners presented in Perspex boxes and illuminated by fluorescent lights, to his auction record breaking steel sculptures, and even right down to his awful paintings, which explore the temporal birds nest of time from antiquity to now, Koons’s work is produced by many, many people, and various technologies. The result is the removal of all traces of the artist’s hand, thus revealing the systems of production—and reception—from which the objects rendered have materialized and mutated. (I can see Koons now if he were to read this, nodding wide-eyed, breathing: “that’s evolution.”)

In this light, consider Degas’s bronze casts, rendered from clay mixed with beeswax so the artist was able to work on them over time, leaving his fingerprints as physical remnants after his figures had been reproduced with a harder material. With no fingerprints to show, Koons has become the 21st Century machine Warhol always wanted to be and more: a desiring machine. An advocate—and avowed dependent—of the (nefariously) productive forces that shape and define the system he views as organic: A system that is defined by the unstoppable forces and ambitions of human nature that propel its progress. (Maybe that explains that Vanity Fair picture of the sixty-odd Koons pumping iron in his private gym—we are the bodies that make this system work.)

The rub for the haters is that Koons is not leveling a critique at what he represents: rather, he is engaging with it, and producing reflections of the zeitgeist with the same sense of uneasy ambiguity with which Warhol navigated his own role as a commercial artist during his own era. How else might we read such oft-quoted Koons quotes as this: “whatever you respond to is perfect”? In this statement, Koons retains control over the means of his own production, yet relinquishes the production of meaning into a rhizomatic field—infinite, expansive, and anarchic—that is populated by anyone who cares to have an opinion. In so doing, the true ownership of Koons’ work—of its meaning and significance—really belongs to everybody.

And if there was a series that sums the core of Koons’ work in this regard, it is the raucously pornographic Made in Heaven, in which the desire that feeds capitalist production is stripped, quite literally, bare. But here, it is not just the bride—or the groom—who has been exposed. After all, in this section of the show, it is only Koons’s gaze—his naked self poised over the body of his enraptured muse, Cicciolina—that is turned on the viewer. He once told me that the series was all about embracing who we are, and being ourselves.

So why the long faces? Take Gibson (one of the many who found the show depressing), who disdainfully recounted viewing a group of school students “gathered around the enormous Balloon Dog (Yellow) (1994–2000), earnestly trying to capture it with pencils and sketchpads.” He wrote: “On one level, they were the latest link in the chain of artists down the centuries learning by copying the great masters in the museums. But in this case the link had been severed. What aesthetic insight was to be gathered from this exercise? The students would have learned just as much about form, proportion, texture, and the rest from drawing an actual balloon dog.”

This was to support Gibson’s rant that Koons “possesses no real imaginative gifts and doesn’t seem to understand what artists do. Real artists take raw material and transform it. Even a Duchamp readymade is transformed, through its altered context rather than changes to its physical form.” But let’s take a step back for a moment. As an art student once myself, this sounds like the coolest exercise ever. Then there is the sensual impact: a balloon that has been rendered hard, durable, larger than life, and yet inexplicably soft and accessible in its immaculate, shiny roundness. Strange and alien, but not alienating, this is a material metamorphosis, in which latex becomes steel, and the transient ephemera of "now" is immortalized in contemporary “stone”.

Superficial or not, this adds another dimension to Christian Viveros-Fauné’s description for The Village Voice of the retrospective, collated by Benjamin Sutton, as one resembling “less a curated exhibition of radical art than a grown-up’s fantasy night at FAO Schwarz.” Is this a bad thing? The sense of being in a grown up fantasy land not unlike the world of Willy Wonka? Are we to forget that as much as this earth is wretched, it is awesome, too, and really, really weird? Take Koons’ image of Gretchen Moll straddling an inflatable dolphin—a nod to inflatable porn that provides yet another nod (or kneel) to the all-too-human perversions that lurk just underneath consumerism’s smooth and unnervingly playful veneer.

Because this is the thing about Koons: in many respects, capitalism is his medium, and he plays with its systems, its agents and its toys while inviting us to play with him; and, as is the case in a free market, we are free to do as we please with the invitation. But is this a challenge? Like with most commercial products and brands, American Idol included (here’s looking at you, Thomas Crow): you decide, because you can.—[O]