In Focus: Grupo Frente

Installation view: Group Exhibition, Grupo Frente, Galerie Lelong & Co, New York (22 June–5 August 2017). Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co, Paris/New York

The 1950s saw the dawn of a new era in Brazil. This period of intense modernisation and transformation spearheaded by post-war industrialisation and democratic ideals also led to a heightened awareness of avant-garde concepts, which pointed towards the possibility of greater autonomy in art. Construction, mechanisation, scientific and technological advancements were at the core of societal development. Rio de Janeiro's and São Paulo's Museums of Modern Art were both inaugurated in 1948, and the first Bienal de São Paulo happened in 1951. Both developments gave local artistic activity more visibility and support, and stimulated more encounters in Brazil between practices and ideas from other areas of the world.

At the forefront of change in art were theorists and artists who rejected the traditional figurative and nationalistic styles of painting predominant in Brazil at the time. Some of these figures belonged to the artist collective Grupo Frente, which was active in Rio de Janeiro between 1954 and 1956. Grupo Frente is less spoken about beyond Brazil than the independent and world-renowned practices of some of its members, such as Lygia Pape, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, though this is now changing. The group's production was the subject of a recent exhibition at Galerie Lelong & Co. in New York (22 June–4 August 2017). Among the artworks on display were early works by Pape and Oiticica, both influential innovators in the experience of art and the focus of recent solo exhibitions at The Met Breuer (Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms, 21 March–23 July 2017) and The Whitney (Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium, 14 July–1 October 2017).

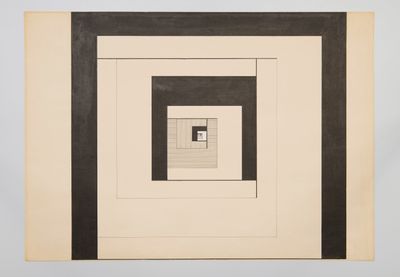

Founded by Ivan Serpa (1923–1973), an artist and educator who taught at Rio's Museum of Modern Art (MAM-Rio), Grupo Frente was composed of artists working in different styles. These artists were united in their rejection of academia and mainstream ideas, and in their response to the rhythms of the rapidly changing modern world around them through art that was, for the most part, geometric. Serpa's suite of four gouaches and India ink on cardboard Untitled (1953), for example, holds groups of black boxes and fine lines in different colours, which at times are slanted and interlock demonstrating a desire to explore the relations between them but with no apparent directives prescribed.

Yet, despite their predominant geometric abstractionist style, the group was not bound by the rigid rationalism that guided their purist counterparts in São Paulo: Grupo Ruptura, founded in 1951 by Geraldo de Barros, Waldemar Cordeiro, Luiz Sacilotto, Lothar Charoux, Kazmer Féjer, Leopoldo Haar and Anatol Wladyslaw, withJudith Lauand and Hermelindo Fiaminghi joining later. Grupo Ruptura followed the directives promoted by Swiss artist Max Bill, who was for a period Director of the Ulm School of Design, in Germany, a descendant of the Bauhaus and responsible for the first international concrete art exhibition that took place in Basel in 1944. Firmly rooted in an abstraction free from associations to observed reality and symbolic meaning, the concrete movement was informed by constructivist principles and neoplasticism, which meant Ruptura often blurred the lines between art and industry. Ruptura, an exhibition marking the launch of Luciana Brito Galeria's NY Project, the São Paulo-based gallery's New York outpost, is displaying the group's production from 6 September to 6 November 2017.

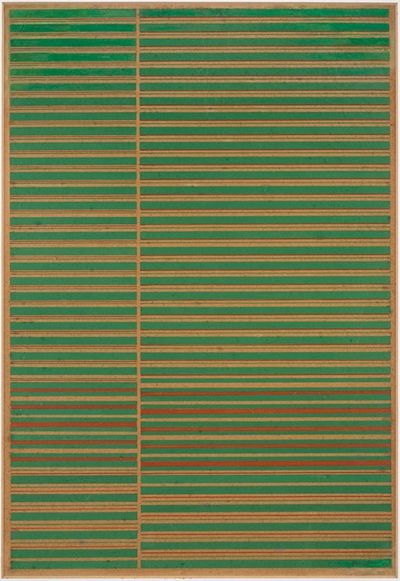

Opposing Ruptura's sober approach, Grupo Frente benefitted from Serpa's prior experience working in a psychiatric hospital developing new therapeutic procedures with critic Mário Pedrosa, who came to inform and accompany the group's production closely alongside his colleague Ferreira Gullar. Though rooted in the geometric abstraction of concrete art, openness to experimentation and a lack of artistic censorship was an important part of Frente's ethos. This posed an inherent contradiction to the principles of their orthodox counterparts, and gave them the freedom to experiment with new techniques and materials. Lygia Pape's woodcut prints from the 'Tecelares' ('Weavings') series made during her time in Grupo Frente, for example, were transgressive in their use of an aesthetic and medium that had been until then associated with craft and folk-imagery (as argued by critic Paulo Herkenhoff at the time of Pape's 2012 posthumous retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery in London, Magnetized Space). In these prints, Pape explored simple geometric forms and explored texture by way of the Japanese paper they were printed on and the effects of the wood veins' imprints to the composition, which were beyond her control.

The group had their first exhibition in 1954 at the Ibeu gallery in Rio, under the critical guidance of Ferreira Gullar. They also exhibited their work in 1955 at MAM-Rio for which Mário Pedrosa wrote an introductory text. Exemplifying how pivotal these artist collectives were in stimulating the vibrant dynamics and polarising ideas at the forefront of the brimming changes taking place in Brazil's art scene throughout the 1950s, Grupo Frente and Grupo Ruptura joined forces to exhibit in the 1st National Concrete Art Exhibition organised by the São Paulo faction. The show took place in São Paulo's Museum of Modern Art (MAM-SP) at the end of 1956, and in Rio's Education and Culture Ministry (MEC) building in early 1957.

On the freedom Grupo Frente experienced in developing their practices, Brazilian critic and professor Luiz Camillo Osorio, who wrote the introductory text to the Galerie Lelong exhibition catalogue, emphasises the influence and role of Rio's Museum of Modern Art (MAM-Rio) in enabling the group at the time, when the institution was exploring the 'political-pedagogical commitment' of the modern museum through a 'blend of new technologies, aesthetic education, and community feeling'. As a teacher at that museum, Serpa's guidance stimulated Grupo Frente members to address geometric abstraction as a space of free thought and experimentation, paving the way for questioning the possibilities in art, all that it could be, and the experiences it could enable. The group's interest in the sensorial and expressive qualities made possible through art represented a rupture that demonstrated a latent level of comprehension that the societies occupying Brazil's modernising cities were integral to their culture and identity.

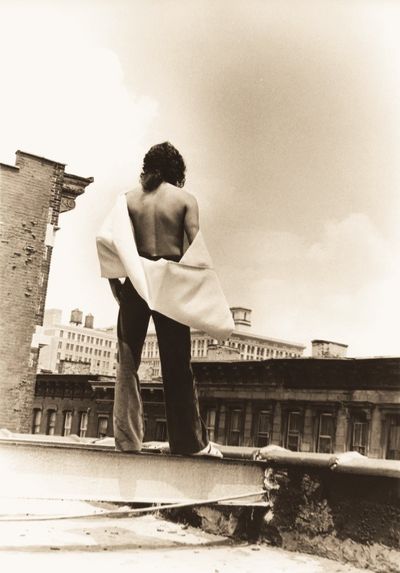

This sensitivity would manifest strongly in later pivotal artworks made by Clark, Pape and Oiticica after Grupo Frente's dissolution, with the founding of the Neoconcrete movement that explored the relationship between artwork and viewer, fostering social engagement and audience participation. Today, Oiticica's small, simple geometric paintings in blocked colours, such as Grupo Frente (1955), can be understood as omens of the transgressive artwork he would go on to make. In later pieces, the artist would liberate colour and form into space with his three-dimensional hanging oil-on-wood Relevos Espaciais (1959), explore performance and social engagement with his wearable Parangolés (1964–79) capes, and further audience participation and the experience of art with immersive installations (examples of which are currently displayed at the Whitney Museum of American Art, To Organize Delerium, 14 July–1 October 2017).

Hindsight lends itself well to observing the evolution of Grupo Frente's artists and how the experimental seed sown during their time under Serpa's tutorship contributed to fostering a mindset that led them to fold their concrete geometries out of the two-dimensional surface plane and into the world. Lygia Clark's dexterity in creating compositions using geometric forms arranged to create optical qualities that seemed to undo the flatness of the surface, demonstrated an intention to project beyond the limits of the picture plane. This is the case with the collage Estudo para plano em superfície modulada No. 4-Série B [Study for Plane in Modulated Surface and the painting Superfície Modulada (Modulated Surface)] (1956)—works that seem to prefigure the artist's interactive folding aluminium sculptures Bichos (1960), made from shaped and articulated metallic sheets held together by hinges so that viewers could handle and rearrange them. The Bichos primordial structures were designed by the artist, as their names indicate, to resemble (abstracted) critters (bichos, in Portuguese). Made after Clark co-founded the Neoconcrete Movement (1959) in Rio de Janeiro with Lygia Pape and others, the Bichos sculptures were a groundbreaking milestone in stimulating audience participation in the visual arts. They were recently displayed in Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art 1948–1988, one of the most comprehensive retrospective exhibitions of her production to date, at New York's MoMA (2014), which brought together 300 of Pape's artworks, including examples from the aforementioned 'Modulated Surface' series made between 1954 to 1958.

What on the surface appeared to derive from movements that had already surfaced around the globe, the artwork made by Grupo Frente stands out in its establishment of a fertile territory that stimulated experimentation, ignited a greater sense of place, and contributed to a significant renewal in Brazilian art. Aside from Frente's valuable contribution to the development of geometric abstraction locally, its greatest legacy is arguably that of an enabler and connector of some of the greatest minds dedicated to making art in Brazil at the time. Under the auspices of the Neoconcrete movement, which splintered from the concrete directives in 1959, Lygia Pape, Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Ferreira Gullar and others set out to search for 'new expressive space' that could be constructed by exploring viewers' direct contact with artworks. They would go on to foster significant developments and radical change in the experience of art, primarily in assigning the viewer an active role through participation, which heightened art's social capacity and which has profoundly impacted the production and experience of art since. —[O]