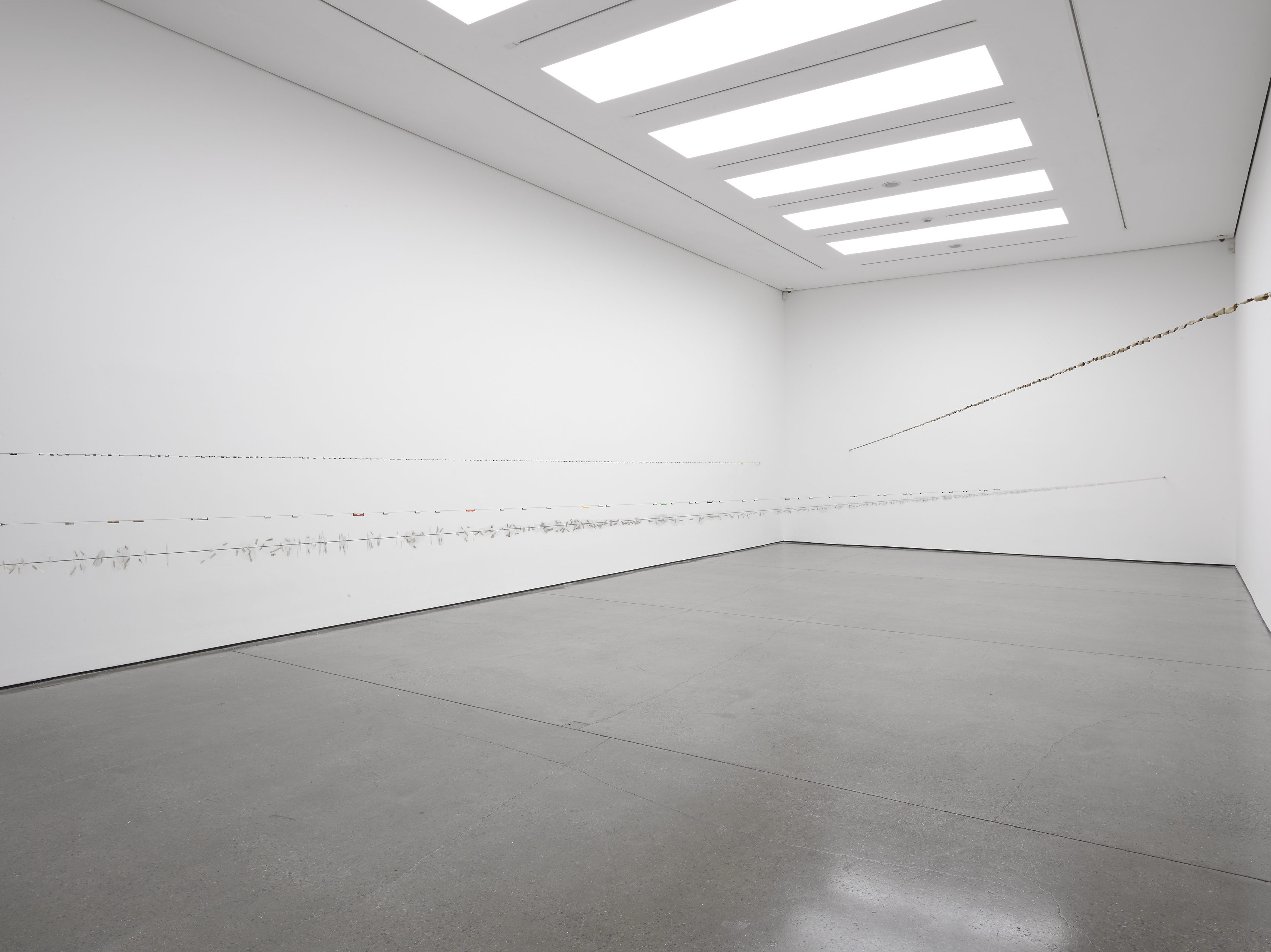

Jac Leirner at White Cube Mason's Yard, London

Jac Leirner’s recent solo exhibition at White Cube Mason’s Yard offered up a very personal body of work. The title alone, ‘Junkie’, alludes to its intimate nature and the works that make up its installation say even more. Comprised of sculpture and photography, a large part of the show is made up of a series of photographs of different sizes arranged across various wooden rulers. Hung on the gallery’s basement walls, the visual impact is of a timeline that represents Leirner’s three-day drug binge in 2010, which this show commemorates via a series of photographs that feature rocks of cocaine sculpted into various images—from a face to a heart—positioned on a table, which one imagines acted as the centre stage of Leirner’s manic three days. Other works can be described as assemblages comprised of common, readymade objects, from bottle caps to worthless cruzeiro notes: it is a kind of readymade geometric abstraction using the scraps of our existence. As the exhibition statement notes, ‘The whole ensemble seems to present a sense of connection and equilibrium that drugs might promise to an addict or, equally, art might bring to the viewer.’ This conversation explores the connection Leirner draws between addiction and art making through a discussion on her White Cube show.

Junkie, your latest exhibition, brings together new works that were apparently assembled and photographed during a cocaine binge you had over three nights in 2010. I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about what is in this show, and what memories these works trigger for you? I'm thinking here of the cocaine rock that is featured in numerous images. Carved into the shape of a heart, or a bust. It is as if you are seeking beauty, or even reason, in an urge for release. Or, as the use of levellers in your installation perhaps suggests, a balance.

Beauty, balance, reason, these are for sure important elements when I am trying to solve the equations I establish when thinking about an artwork. When I see these images side by side, or the Rizla cigarette paper sequences, or the cigarette ends that were laminated and cut as petals to be punched so that they could become tiny parts of a whole, my eyes can’t stop or focus. They keep going from one spot to the other. And I think about the time it took me to get to the final engine of the whole, the blood in my nose, the hunting of the objects, the moment my grandma gave me the golden key chain, which I reproduced for one of the images. These works trigger infinite aesthetic and formal decisions related to a series of works, and to my personal folklore: my story.

The exhibition presents detritus from your addictions using a formal compositional logic that you have used throughout your career, in which you arrange found objects together as a way of measuring time, quantity, and value, as exemplified in the works you produced in response to the catastrophic devaluation of Brazil's currency in the 1980s, in which worthless cruzeiro notes were strung together to form sculptural curves and lines. I wonder how you might relate this new, and highly personal body of work, to the works you produced in the 1980s and 1990s? I am thinking here of the formal approach to the found materials you have used to produce your assemblages throughout your career, and how this formality balances with the subject matter. In other words, from the vantage point of your White Cube show, what perspective do you have on your life's work?

Most materials I have used along the last decades have a couple of things in common. Everybody has easy access to them, or have them in their own pockets. They are related to everybody’s lives. They are often insignificant in formal terms; in this sense, they give me a hard time to lead them into a special placement, to give them a real body or turn them into sculptures. By adding time and a lot of thought and sight to this exercise, they gain an aura that wasn’t there before. This is the most precious quality I have given to the work. All the rest is stuff.

One thing I wanted to ask about is the relationship between addiction and art you point to in this exhibition. This is suggested most overtly in one image that features MoMA stationery alongside cocaine. How does this 'addiction' relate to the compulsive need to make? That is, to collect and re-form scrap and waste into object systems, or sculptures? In the White Cube show, there is a real sense of a struggle; of needing to engage with the mania addiction can so often bring, while trying to keep a distance from it. An almost unbearable tension that contains within it a kind of pathetic beauty of some kind; pathetic in the sense that the moment you have caught—that three-day binge—is essentially one of total surrender.

Thank you for your words. I can see myself there, as an artist totally taken by language. Institutional Ghost, the photograph that presents MoMA’s pencil taking part on the composition, is the only explicitly metalinguistic piece in this series. I did other series where I used museum plastic bags from their gift shops or business cards from professionals of the art scene that also went back to their walls. But in both cases I was very objective. At the White Cube show, everything, not counting the tiny cocaine sculptures or pot leftovers, that I kept along decades are all presences of little things and colours and lights and shadows were built in very subjective situations. Every move I made during these nights were consumed with, as you say ‘struggle’, a ‘compulsive need to make’, and ‘unbearable tension’.

How do you fit yourself into the tradition of geometric abstraction? I ask this question also with the fact that you come from a collecting family in mind—I wonder if you could talk about this background, and how it influenced your career?

I can say that my parents were the first ones to put together a real collection of constructive art in Brazil. They started it when there was no market or bibliography on the subject, around 1961, and it took them more than 30 years to build this most amazing ensemble which is now at the Houston Museum of Art. They made history in this sense. The whole spirit of this time was being added to at home, piece by piece. So I grew up knowing and following exactly the spirit of two passionate kids with a love for beauty, elegance, and a lot of focus. They weren’t buying all kinds of stuff. And it wasn’t about investment, since what they bought then had no value at all; they couldn’t afford European modern art, and they would have bought these, too. They were enchanted by their discoveries. And they would hunt for this art every single weekend. Whenever they had a real opportunity they would go for it—I am a witness! So I would get a Mira Schendel as a 15-year-old birthday gift, or a Metaesquema by Helio Oiticica as a wedding gift.

If you were to name some of the key moments in your life and work, what would they be? And further to this, who have been your greatest influences on your life and work as an artist thus far, particularly in terms of how you approach the role of the artist?

The first key moment: going on vacation in ‘68 or ’69. I was 7. Ravels’ Bolero played on the car radio. I couldn’t deal with it. I got totally taken by it, out of myself, standing inside the car. One day, I realised that I have been doing the same thing as I did that day, by repeating the same phrase again and again until I get to the whole.

The second key moment: seeing Death in Venice by Luchino Visconti. I was 14 and again it was Mahler’s music that lead me to an unknown situation, plus the suffering of the artist towards beauty, and the movie itself, Tadzio, the discovery of language and finally Thomas Mann, all in one. And then, Rashomon by Kurosawa. All the movies in the world and all poems that I could read.

In Brazil, three artists had a key role in my experience as a young artist. They were older but I hung out with them: Tunga, Cildo Meireles and Jose Resende, who was for many years my partner and is the father of my son, and is in my opinion the greatest.

Do you remember the moment you knew you wanted to be—or knew you were—an artist, and were there key moments/encounters in your life that helped you along your path?

I never wanted to be an artist. I wanted to be everything else, from a professional athlete to an oceanographer. The thing is, I loved drawing and I thought I might become an architect but when I got to the fine arts college I realised I was at the perfect place. I felt in love with the whole situation and worked for the teachers, got a scholarship. I thought that maybe, eventually when I got to my eighties’ I might take part in a Venice Biennale.

Julio Plaza wrote the first essay about my work. Guy Brett brought me to Birmingham in my first international group exhibition and was the first foreign writer and curator to embrace my work. Gill Hedley worked on a whole package that brought me to Oxford as a fellow at the University College, a guest of the British Council and as an artist in residence at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford where David Elliot, who was the director invited me for my first solo show ever in Europe. Then Kathy Halbreich invited me for a residency and a solo show at the Walker Art Center, and Rob Storr took a piece of mine under his arm to be acquired by the board of the Museum of Modern Art. This was 1991. A few years ago, he brought me to Yale School of Art for a residency and an exhibition at their gallery. Frederick Bohen Henry, the president of the Bohen Foundation was like a mecenas for ten years of my life. He would acquire work after work and then donate all of them to a great American institution. Receiving the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship was also a key moment in my experience, but I never use the word career. It doesn’t suit me.

What advice would you give to young artists today?

Say no to drugs, as you may be an addict. Focus. Spend your time in museums when you can. Pay attention to other languages. Go to the movies, listen to good and to bad music, read good books, Work hard in the case you like doing it. If you don’t, find something else to do because you are at the wrong place. Don’t fall into the illusion that art and market mix. They have absolutely different natures. With very rare exceptions.

Never attach the word ‘art’ to other words such as gender, globalisation, crime, technology, sex, economy, movement, etc etc. Leave these subjects to people that know them better than you. Stick to art and only art. —[O]