Zilia Sánchez at Galerie Lelong, New York

In the 1950s, on a Havana rooftop and reeling from the recent passing of her father, Cuban artist Zilia Sánchez (b. 1926) had an epiphany. A gust of wind blew a hanging laundry sheet (the very one her father had been lying on when he died) against a pipe and a wall, and in its resulting form she discovered an entirely new approach to her work. She abandoned painting on flat surfaces and began pulling canvas tautly over oddly-shaped wooden armatures, creating curved peaks that opened painting up from its conventionally rectangular state. Introducing three-dimensional forms to her work, Sánchez’s shift challenged the preferred frontal view of artworks by interrupting the face-on gaze and coercing it around corners.

Sánchez’ work is currently part of the exhibition Diálogos constructivistas en la vanguardia Cubana (Constructivist Dialogues in the Cuban Vanguard) at Galerie Lelong in New York (28 April to 25 June 2016). The show brings together the work of three female Cuban painters who engaged with geometric and Constructivist practices as early as the 1930s: Sanchez, Amelia Peláez (1896-1968) and Loló Soldevilla (1901-1971). Peláez was an important Cuban painter of the avant-garde generation. Although her work is representational, her Cubist-style still lifes (1940s-1960s) and ceramics (1950s), (both included in the exhibition), demonstrate an interest in line, colour and geometric shape that resonates with her younger compatriots’ concern with Geometric Abstraction. Soldevilla was an early leader in the development of hard-edged, geometric art that began to emerge in Cuban painting in the 1950s and which eventually coalesced under the rubric Los Diez Pintores Concretos (Ten Concrete Painters).

The youngest of the three women, Sánchez acknowledges both the influence of Peláez and Soldevilla. She too enjoyed the support of the Lyceum Women’s Club, an important social and intellectual institution in Havana that has supported the Cuban vanguard since opening in 1928. All three women were heavily influenced by time spent overseas: Peláez’s and Soldevilla's painting being affected by time in Paris, and Sanchez by time she spent in Madrid and New York. In her own experimentation with colour, line, geometric patterns and grid-based compositions, Sanchez, however appears to have taken their shared concerns to an altogether more sensual place.

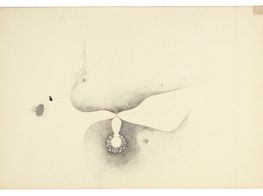

While some critics have shied away from this conclusion, Sánchez’s work is arguably erotic in appearance. The forms in her works—being neither painting nor sculpture, but equally both—swell and protrude from the wall, evoking female body parts. Often oval or circular in shape, the works feature elusive arcs, delicate half-moons, and undulating creases and folds, presented predominantly in delicate baby blues, soft greys and white. The painting Lunar con Tatauje (Moon with tattoo), 1968/69 consists of two half-circle canvases nestled together, protruding at the middle to make an overtly sensual shape. Three circles of colour create an ascending pattern of white, grey and fleshy peach from the work’s centre. Across the surface—and disrupting its pristine perfection—is a series of delicate and lyrical sketches, almost subconscious doodles.

Ocula’s Eva Fuchs spoke to the 90 year old Sanchez about her work, her relationship with Peláez and Soldevilla, and her latest exhibition in New York.

You created your first shaped canvases in the early 1950s and subsequently developed your signature style of stretching canvas over wooden armatures. How did you first decide to use a shaped canvas? What triggered this?

The first time I got the idea was after my father had just died. He has been very ill and I suffered a lot from his death. I was crying on the rooftop of my building and through my tears I saw a white sheet that was hanging out to dry. It was the sheet of the bed my father had been lying in. It was flowing with the wind and hitting against a pipe and a wall. I saw the form that came about because of that, and suddenly I saw the sheet like a painting. I saw that I had discovered a painting that I had to make. Even though it was such a sad moment for me, I made sure I remembered it exactly, so I would be able to make it precisely as it was.

![Image: Zilia Sánchez, Lunar con Tatuaje [Moon with Tattoo], c.1968/96. Acrylic on stretched canvas. 71 x 72 x 12 inches (180.3 x 182.9 x 30.5 cm) © Zilia Sánchez.](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/68/681fb329-053f-4663-8aac-d2a914b29caa.jpg)

Your works have a very biomorphic appearance; one could almost see a torso or women’s breasts—do you see the canvas as a kind of body? What is the relationship between the body and your work?

Yes, my works definitely have a strong connection to the body. I’ve just told you about how I first started to make the shaped canvases after my father’s death; I felt like the sheet I had seen blowing in the wind was like his skin, and the wooden construction beneath it resembled a skeleton. I had to eternalise it because of this. It was a very emotional moment and still is an emotional memory. It felt like I saw my father’s soul leaving his body.

You were working as an artist in the 1960s and have continued to do so. I have read that your work can be related to feminism. Did or do you intend your work to be read in relation to feminism?

No, there has never been a feminist aspect to my work. My work has always been very female, and I always thought about feminine, erotic forms when making works. Feminism feels too strong, too violent for me.

![Image: Zilia Sánchez, Azul azul, [Blue blue], 1956. Acrylic on canvas, 21 x 23 inches (53.3 x 58.4 cm) © Zilia Sánchez.](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/9b/9b4313a7-5098-4909-b165-bf35427e150e.jpg)

This exhibition shows aspects of your work in relation to two other artists, Loló Soldevilla and Amelia Peláez. Can you talk about what connects their art to yours? What was your relationship with these artists like?

Of course Loló and Amelia were not the only artists I admired, but I always felt connected to them. They were like my teachers, and I was attracted to their works. I have always been aware of the exhibitions they were having and would attend their openings. Amelia and I were in a brief ceramic course together, but that was already towards the end of her career, shortly before she died. I have known Loló personally as well. There were also male artists that I was following: Wifredo Lam especially interested me.

In her essay Between the Real and the Invisible Ingrid W. Elliott writes about the interest in architecture that is common to your (Soldevilla, Peláez and Sanchez’s) oeuvres. Can you tell me more about that?

Yes, Amelia made murals and Loló was teaching architecture and a lot of her works were three dimensional. I have always been interested in architecture and wanted to study it. I started taking courses in linear drawing at the university, where they focused a lot on mathematical constructions. However, when the Revolution happened and the university closed, I never got to pursue an architectural career. But yes, I really liked it. When I was in Puerto Rico I made a mural in Laguna Gardens and planned it myself. I even made the moulds, first out of canvas and then turned them into concrete. My paintings have an architectural element as well: the three dimensionality. The affinity to architecture is something that has always been inside me, it is something instinctive.

Loló Soldevilla, Amelia Peláez and you were all part of the Lyceum Women’s Club in Havana. Can you tell me about this space and how it was important for you?

The Lyceum started as a women’s social club in 1928. Over time it evolved into a place for exhibitions, conferences, meetings, gatherings and more. It was a space for different types of artists, a lot of them were autodidacts. After the revolution it slowly disappeared, similar to many other institutions of the time.

Loló Soldevilla has spent several years in Paris and has been significantly influenced by the artists she met there. You have spent a lot of time abroad as well, namely in Madrid and New York. Can you tell me if and how traveling influenced your work?

I never traveled extensively, but I did travel intermittently between Cuba and Spain from 1957 to 1961. When I was abroad I was mostly working, in Madrid where I was involved in the restoration of art works at the Museo del Prado. I felt good in Spain, I was doing what I was interested in and liked. It also helped me to understand painting from another perspective, seeing all those works, being taught about varnishes; I learned a lot. I really wanted to stay, but in the end I missed Cuba and my family too much. My mom would call frequently and ask when would I come back; my parents were very worried about me. It was tough to be away from them, otherwise I would have stayed.

![Image: Loló Soldevilla, Carta Celeste: Noches en el Cosmos, [Celestial Letter: Nights in the Cosmos], 1958. Oil on canvas, 26.75 x 27.5 inches (67.9 x 69.9 cm). © Loló Soldevilla. Photographed by Fernanda Torcida,](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/43/433bbb0e-b8ea-4cc6-a535-b89c4272b904.jpg)

What was it like to work in the years of the Revolution? Is there a connection between your radical art making and revolutionary Cuba?

During the time of the Revolution I was already in Spain and studying restoration at the Prado. I remember how my mother called me and said: “Don’t come back now, we have revolution!” I was very worried for my brother and my family.

Is there an aspect of self portraiture in your work?

Yes, my works are portraits, but interior ones. They show what I am hiding. I use them to express what is within me; I am not very vocal and use my art to communicate.

The works in this show are all earlier pieces. Are you still making art today?

Yes, I am still working! At the moment I have four panels in my studio ready for the next exhibition at Galerie Lelong and I am discussing the works with Mary Sabbatino—she is fantastic! —[O]