With her paintings set to be the subject of exhibitions at Gagosian Hong Kong and Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles, and recently joining Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, Li Hei Di is on a roll for 2023.

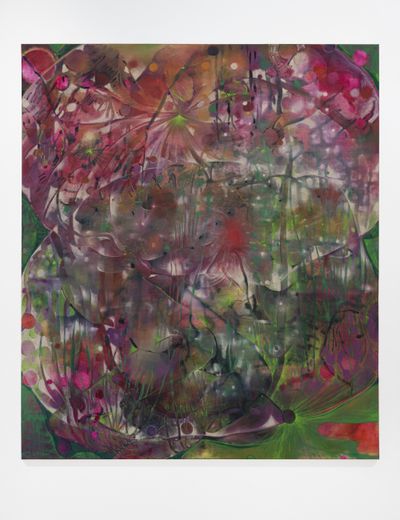

The young Chinese artist is known for her divinely effervescent body of work that explores the depths of repressed human emotions and sexual desires, thriving in the space between abstraction and figuration.

Reflecting on her practice thus far, Li Hei Di discusses the making of her latest work, and the books and films that inspire her.

You've just joined Pippy Houldsworth Gallery and recently featured work in their group show Conscious Unconscious (12 January–4 February 2023). Could you tell us a little about the inspiration and process behind your most recent paintings?

When I was studying at the Royal College of Art in London, I became infatuated with themes exploring intimate relationships. I began painting abstract faces and figures that gradually morphed into fragmentations of physical features like limbs, nipples or breasts.

The erotic ambiguity of my paintings feels like I'm capturing a ghost of something not quite abstract, but not quite figurative either. This ephemeral style permeates my work and grants me space to navigate stories of repressed desires and provocation.

When I'm working, I often listen to audiobooks, more so than to music. I enjoy stories and writing, so I try to paint in the way of telling a story or making a film.

The space between abstraction and figuration is clearly an important part of your work. Are your compositions intended to be fragmented, dreamlike spaces, or are you drawing on particular landscapes and portraits?

I prefer to have some sort of allusion to figures in my work that look abstract from the outset. Often my work will start with figurative elements that suggest as though someone has dissolved into the environment I've manifested.

I recently discovered Chinese author Mo Yan. He wrote the book Big Breasts and Wide Hips (2005) which follows a story of a mother who keeps giving birth to daughters in China during the 1930s. When she finally births a son, he is spoiled and grows up entirely obsessed with breasts.

He sees breasts in everything—in food, nature, people. By the end, all these breasts come together in a trippy depiction of nipples exploding in the sky. That imagery really haunted me and now I can't stop seeing every point of light as a nipple. I started painting figures by these points of light, hinting at characteristics of desire and sex that are repressed through abstraction and censorship.

How do the novels or films that capture your imagination appear in your work?

I often become fixated on the things that inspire me. When they resonate in my work it happens organically, as opposed to planning out a work around the imagery from a book or film.

Most recently I've been reading The Book of Goose (2022) by Chinese-American author Yiyun Li. Her book explores narratives surrounding rural postwar France and female friendship.

There are scenes in the book where the characters are deep in the countryside, laying on grass next to water. Those moments where the figures almost dissolve into the landscape bewitched me. I began painting a lot of green and intertwining abstract shapes with landscape features.

After witnessing the tragedy and resilience of Chinese people in November 2022, I started painting with a lot of red. I felt a shift in temperament from the desire to make a kind of Teletubbyland painting, to feeling uncomfortable and frustrated and wanting to portray that intensity of emotion.

Did the disguised personal comic references featured in your exhibition Tits at Dawn (11 November–18 December 2022) at LINSEED in Shanghai arise from your interest in the limitations of censorship, or was it something that you just find amusing?

The limitations of censorship is something I've always found funny. As a teenager at school, I remember wanting to paint naked figures but feeling restricted when I knew my parents would ask to see what I've been working on.

Instead, I learned to paint a small section of the painting with something sexual. I'd paint scenes of people having sex in a hidden area at the back of the canvas, surrounded by aesthetic interiors or landscapes.

I love the inclusivity of art. My parents, even though they don't know anything about art, see my work and enjoy the experience of it. I want to include everyone so that there might be an abundance of different perspectives when looking at my work.

When my friends see my paintings, they often immediately see sexual imagery even though I didn't actually try to feature anything specifically sexual at that time. My friends know the way I am, so they over sexualise parts of my painting.

On the other end of the scale, there are some people who are oblivious and believe it's just a pretty landscape painting. I find that aspect of my practice really amusing.

What does a normal day in the studio look like for you?

I've been in my current studio in Kensington since the end of July last year. I usually go at least four or five times a week and stay very late, sometimes until 2am. I won't be painting the entire time, sometimes I'm watching films or replying to emails.

What's next for you? What exhibitions do you have coming up?

I have one painting in the group show Uncanny Valley (31 January–4 March 2023) at Gagosian in Hong Kong. I had such a good time with this painting, it felt like everything came together so well.

Later in the year I have my U.S. solo debut with Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles which I'm really excited for. Further down the line in 2024, I will have my first solo exhibition with Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London. —[O]

Main image: Li Hei Di, Liquid meadow in the lust of dawn (2022) (detail). Oil on linen. 310 x 170 cm. Courtesy Li Hei Di.