contact s. m. [from Lat. contactus, der. of contingĕre «to touch»]

Photograms came about before the invention of the camera. That is why we call the process, 'camera-less'. This photographic technique involves placing an object between a piece of paper and a light source to create a unique image that resembles the shadow or silhouette of the object used. The ranges of tones achieved in the image are dependent on the material consistency of the object. Unexposed areas of the paper that received no light appear white, those exposed for a short period or through a semi-transparent object appear grey. Fully-exposed areas are black in the final print.

The first practitioners in the nineteenth century turned to their gardens, drawing on subjects and ideas from the realm of botany to create their photograms (Henry Fox Talbot called his photogenic drawings). In their eyes, botanical photograms possessed an authenticity that was based on their being in direct touch with the specimens of nature. Contact (between the object, light, and surface)was constitutive of the image, and by extension, of the concept of objectivity itself.Yet, direct contact could sometimes entail a deficit of the visual, and a general lack of detail.Too close to the 'truth' (or the object) the photograms resulted in ambiguous identification, and were therefore of inconsequential scientific value. Indexical truth-to-presence sacrificed truth-to-appearance, and photograms came to be regarded as nothing more than an infantile stage of negative-to-positive photographic representation.Treated as an inferior process when compared to camera photography, photograms became equated to a 'feminine' pastime method to reproduce 'trivial' objects(usually, ferns, lace, seaweed, and umbelliferous plants). The process became unimportant, cast aside (not quite superseded), unable to support the more 'serious', matter-of-fact, documentary claims of the photographic apparatus.

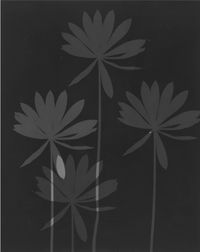

Painter Anwar Jalal Shemza and artist Simryn Gill revisit the process of the photogram in their distinct series. Both artists instigate a play with light in rendering selected botanical subjects, creating one-to-one unique copies of the originals. Flowers, leaves, and stems are lifted out of their environments, and turned into abstract impressions. Shemza and Gill remind us that light has the power to touch objects and produce images, but also that light alters the nature of the substances used—e.g. silver halide. Contact between object and light can yield a tiny and crisp image. But it can also generate visual records that are performative, serendipitous, and subject to chance (contingent). Such images, stretch our understanding of the photogram. To observe these might be the opposite of illumination; we are left in the dark as to their origin or nature.

In 1961 painter Anwar Jalal Shemza moved with his young family toStafford in the British Midlands, close to where his wife's parents lived. Here, he painted, taught, and spent long hours working outdoors in the large home garden. Designed and planted by an art teacher at King Edward VI Grammar School, it included various flower beds, lawns, vegetable orchards, and seventeen fruit trees.Gardening became a therapeutic pursuit, and restored tranquillity and peace of mind. It also brought back memories. As a child inLahore, Shemza had loved visiting the city's lush, quadripartite gardens (the Čahār bāgh, literally, 'four gardens'). These carefully-designed landscapes typically featured a central water channel with others leading off it at right angles with flower beds situated between them. It was the Mughal Emperor Babur who favoured this ornate, man-made garden landscape design, and for this reason, had introduced it to the city in the sixteenth century.

In Stafford, Shemza also devoted some of his time to making silver gelatin prints. In a series of little-known photograms, we recognise numerous wild English flowers, plants, and shrubs. We find the siliques of the Lunaria annua (from the Latin 'luna' meaning 'moon-shaped'), also called honesty or the pope's glasses. The elliptical transparent bodies float about the space like jellyfish in a sealed jar. Gently tearing the surface of the siliques to remove the individual seeds, Shemza lets a little light through, creating darker creases or patches. The silvery tonal modulations are the result of a calibrated exercise—or controlled manipulation of light. In another photogram, we discern the calyces of the Physalis alkekengi—commonly known as Chinese lantern. The reticulated husks encase two round shrivelled berries, little (orange) globes. The spiky inflorescences of a foxtail (diaspore) curtsy above each.

It may well be that Shemza selected these botanical specimens for their material translucence, transparency, and opacity, in a word, their textures, anticipating the effect of light on the objects on paper. But in other instances, he appears to be more concerned with solid forms, with pattern, and repetition against a darkened background. Ina photogram, we detect the plump thimbles of a blooming foxglove (digitalis, from the Latin for 'finger') pressed in neat vertical rows. Overlapping areas produce greyish tones, lifting the textures off the page. In another image, he places the stem of a large fern off-centre, using the natural curvature of the blade—or frond—to divide the picture plane into three areas. The thick pinnae or leaflets gently adjust to the surface, evoking the structure of a fish endoskeleton, picked clean by time. A similar treatment is reserved for the white petals of bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis). Shemza situates a single flower at the centre of the page: the long wiry stem, literally, a filament of light, slices up the page into two symmetrical parts. The same flower head is exposed twice in the background: we see it on the right and left, softening the overall graphic drama. The white pushes through the structures so that every compositional element resurfaces to set up a delicate contrast on the black rectangle. The effect is to pre-empt any sense of flatness through tonal variation.

After various attempts, through a repeated process of trial and error, artist Simryn Gill produced the photogram series Untitled (fromClearing), ranging in size between 67 x 40 and 75 x 40 inches. It came about in serendipitous circumstances. The Oxford English Dictionary defines 'serendipity' as 'the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident', noting that even scientific discoveries often depend on serendipitous chance observations 'falling on a receptive eye'. Scientific discoveries with the after-shimmer of serendipity abound (think about the salt and silver nitrate days of early photography). Carl Wilhelm Scheele stirred a pot of Prussian Blue with a spoon coated in traces of sulphuric acid in 1782, and created cyanide, (the most lethal poison of the modern era); in 1928, Alexander Fleming, a careless lab technician, returned from a holiday to find a fluffy patch of mould on a staphylococcus culture plate—he had discovered penicillin. Serendipity is ubiquitous, and in literary studies, includes Marcel Proust's chance encounter with a bite of madeleine cake which triggers a rush of involuntary childhood memories, upon which he would base his famous, seven-volume text_In Search of Lost Time_ (published between 1913 and 1927). To make something out of nothing ... To turn loss into a thing.

In Gill's photogram series, we are presented with the body of a canary date palm (Phoenix canariensis) exposed on a defunct roll of Kodak Portra paper. The infested palm was cut down to make room for a building renovation, the roll of paper had been cleared from a commercial printing lab in Sydney (Kodak Portra production was globally discontinued in the early 2000s). Past its sell-by date, the resin-coated silver halide paper was on was its way out, a material with a decommissioned-value. As the paper degraded its whites got duller and its blacks got greyer, the overall tone had become softer, of a muted grey, showing a low degree of contrast. Gill held the body of the palm frond before the paper, and used a horizontal source of light to record the meeting of these two ageing partners. The physical record of this coming together, or touching, stretches our understanding of the simple photogram, as both thing and process.Flipping the image at ninety degrees, Gill leaves us with a vertical, huge seaweed, a kite catching light in a thunderstorm, or is it the fiery feather of a Phoenix, that fabulous bird the Egyptians associated with the worship of the sun?

Dr. Emilia Terracciano, 2023

Press release courtesy Jhaveri Contemporary.

3rd Floor Devidas Mansion

4 Mereweather road

Apollo Bandar Colaba

Mumbai, 400 001

India

www.jhavericontemporary.com

+91 22 2202 1051

Tuesday – Saturday

11am – 6:30pm