Fernando Botero, Maker of Portly Portraits, Dies Aged 91

Loathed by critics, his paintings had more edge than his curvy subjects would suggest.

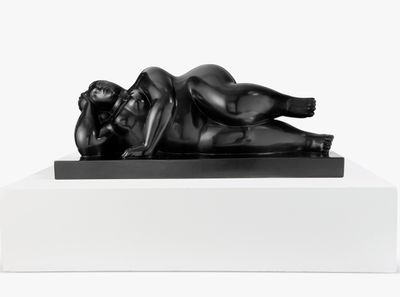

Fernando Botero, Reclining Woman (2010). Bronze. 24.1 x 57.2 x 23.5 cm. Christie's Latin American Art sale, New York, 28 September 2023. Estimate: U.S. $250,000–350,000. © Christie's Images Limited 2023.

Artist Fernando Botero died in Monaco on Friday from complications of pneumonia. He was 91.

'Fernando Botero has died, the painter of our traditions and defects, the painter of our virtues. The painter of our violence and our peace,' said Gustavo Petro, the Colombian president, on X.

Botero was the 44th most searched artist on Artnet's database in 2022, ahead of popular artists such as Francis Bacon, Takashi Murakami, and Jeff Koons.

Reminiscent of storybook illustrations, his paintings of plump figures presaged the arrival of cute, cartoonish work by artists such as Liu Ye and Yoshitomo Nara.

Born in Medellín in 1932, Botero trained as a matador before devoting himself to painting.

He was expelled from his Jesuit school for expressing 'irreligious' ideas in an article titled 'Pablo Picasso and Nonconformity in Art'.

He moved to the Colombian capital, Bogotá, where he gave his first solo show before living in Paris, Florence, and New York.

In 1961, MoMA collected his painting Mona Lisa, Age Twelve (1959).

'They hung it in a great position, and it received tremendous comment,' Botero told Artforum in a 1985 interview.

The acquisition significantly boosted his career, but his subsequent work befuddled and angered art critics.

'It was like I was a leper,' Botero said. 'One critic in particular came to see my work and had to stand in front of it without looking because he said it made him sick. From the public I got the opposite attention.'

Some of Botero's paintings were political, softening up presidents and dictators, and tackled tough subject matter including the torture and abuse perpetrated by American soldiers in Abu Ghraib.

Satire was not his primary motive for enlarging his subjects, however.

'Why don't people laugh at the proportions when they see Romanesque art or pre-Columbian art? For centuries there was this kind of form, and now all of a sudden it is necessarily a satire,' he complained.

'My deeper interest is in the sensual, plastic language of painting and in the expansion of form.' —[O]